I would like to add this explanation as a complement to the rest of answers. I think that the problem can be stated as a rotation problem of $D_n$, the Dihedral group of the $n$-gon. This is only the statement and an explanation of the equivalence.

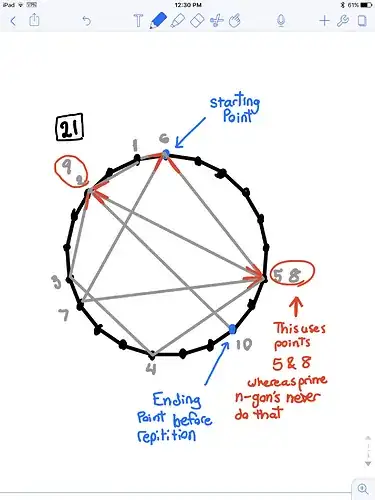

When you trace a line from vertex $v_i$ to vertex $v_j$, imagine that you are not joining them with a line, but rotating to the right the $n$-gon, $k$ times $\frac{360}{n}$ degrees (the angle between two consecutive vertices) where $k$ is the total of rotations of one vertex $v_i$ to the closest vertex $v_{i+1}$, in the decided rotating direction to the desired final $v_j$ that you need to arrive at $v_j$ from $v_i$.

The Caley table of the Dihedral group of the $n$-gon, $D_n$, shows the composition operation between the elements of $D_n$. The composition operation of rotations basically is defined as $$r_ir_j=r_{i+j \pmod {n}}$$

... where $i,j \in [0..n-1]$. The operation is right to left: we apply rotation $r_i$ to the already made rotation $r_j$. The composition operation is the group operation of $D_n$.

Supposing that $I=r_0$ is the initial position of the $n$-gon at the beginning of the conjecture, then you rotate $r_1$ times the angle between two consecutive vertices (this is rotating $\frac{360}{n} \cdot 1$ degrees to the right), then you rotate $r_2$ times ($\frac{360}{n} \cdot 2$ degrees to the right), then three times, etc.

The "jumps", or lines traced between vertices, are equivalent to rotations. Jumping $20$ vertices will be equivalent to applying the $n$-Dihedral group rotation $r_{20 \pmod {n}}$.

So basically $r_{i+1 \pmod {n}}r_{i \pmod {n}} = r_{i+1+i \pmod {n}} =r_{2i+1 \pmod {n}}$. So it is equivalent to make operations in the rotations of the Caley table of $D_n$.

This is an example of $D_5$

$$\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|c|}

\hline

& r_0& r_1 & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 \\ \hline

r_0 & \color{red}{r_0} & \color{red}{r_1} & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 \\ \hline

r_1 & r_1 & r_2 & \color{red}{r_3} & r_4 & \color{red}{r_0} \\ \hline

r_2 & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 & r_0 & r_1 \\ \hline

r_3 & r_3 & r_4 & r_0 & \color{red}{r_1} & r_2 \\ \hline

r_4 & r_4 & r_0 & r_1 & r_2 & r_3 \\ \hline

\end{array}$$

As per your conjecture, we start at $r_0$ (column). We will mark in red $r_0$ because we will assume that the first movement of the conjecture is rotate $0$ degrees, so $r_0r_0=r_0$. Then we apply to the current rotation type, that happens to be again $r_0$, a rotation $r_1$, so we are at $r_1$, now again going to the column $r_1$ now we will apply a rotation of $r_2$, so $r_2r_1=r_3$, so we will mark $r_3$ in red... if we continue the algorithm, we will arrive to a Caley table in which every column has only one visited rotation type.

If we find two rows with the same rotation type marked in red, means that a vertex has more than two lines entering or exiting it.

But, as the other answer said, also holds for $D_{2^t}$ cases, for instance $D_4$

$$\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|}

\hline

& r_0& r_1 & r_2 & r_3 \\ \hline

r_0 & \color{red}{r_0} & \color{red}{r_1} & r_2 & r_3 \\ \hline

r_1 & r_1 & r_2 & \color{red}{r_3} & r_0 \\ \hline

r_2 & r_2 & r_3 & r_0 & r_1 \\ \hline

r_3 & r_3 & r_0 & r_1 & \color{red}{r_2} \\ \hline

\end{array}$$

And apart from those cases, we will find two red marks $\color{red}{r_3}$ with the same rotation type, for $D_{6}$:

$$\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|c|c|}

\hline

& r_0& r_1 & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 & r_5 \\ \hline

r_0 & \color{red}{r_0} & \color{red}{r_1} & r_2 & r_3 & \color{red}{r_4} & r_5 \\ \hline

r_1 & r_1 & r_2 & \color{red}{r_3} & r_4 & r_5 & r_0 \\ \hline

r_2 & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 & r_5 & r_0 & r_1 \\ \hline

r_3 & r_3 & r_4 & r_5 & \color{red}{r_0} & r_1 & r_2 \\ \hline

r_4 & r_4 & r_5 & r_0 & r_1 & r_2 & \color{red}{r_3} \\ \hline

r_5 & r_5 & r_0 & r_1 & r_2 & r_3 & r_4 \\ \hline

\end{array}$$

If we use the Caley table to perform the same original algorithm that the OP defined, then our stop condition is arriving to a rotation of $n-1$ vertices successfully or marking for the second time in red the same rotation type (as in the former case happened with $r_3$).

So basically if my expressions above are correct, your conjecture (including the observation that also the set $2^t$ holds) can be stated as:

$\forall D_n\ ${$\not \exists r_a,r_b,r_c,r_d,r_e \in D_n, a \not = b \ ,\ r_c r_a=r_e \land r_dr_b=r_e $}$ \to n \in \Bbb P\ \cup\ ${$2^t,t \in \Bbb N, t \ge 2$}

where $D_n$ is the Dihedral group of the $n$-gon.

or equivalently:

Def. Set $E_n = ${$e_k: e_k=r_k r_{k-1}...r_0, k \in \Bbb N, k \lt n $}

$\forall D_n\ ${$\not \exists e_i,e_j,i \not = j \in E_n: e_i=e_j $}$ \to n \in \Bbb P\ \cup\ ${$2^t,t \in \Bbb N, t \ge 2$}

That would be the initial point for a demonstration. I am currently reading the book "Symmetry: A Mathematical Exploration (Springer, Kristopher Tapp)" and this conjecture fits very well with the basic concepts explained about the Dihedral group in the book. Is a good reading for beginners (like myself).