The minimal number of squares for rectangles up to longest side 380 is known. The data was calculated for the question "tiling a rectangle with the smallest number of squares". I took a look at hard cases for aspect ratios under 2.

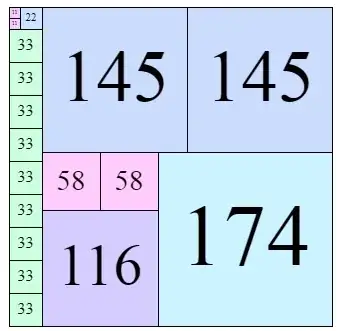

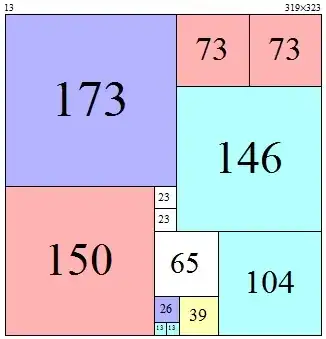

f(323,319)=18. (shown above)

f(323,293)=17. (shown above, along with f(30,293)=17)

f(323,317)=16.

f(323,283)=16.

f(323,281)=16.

Those are all of the cases up to 380 that need more than 15 squares. For 15 squares, add the value 352 as hard.

f(323,X)=15, with X in {256, 271, 277, 307, 313}

f(352,X)=15, with X in {283, 289, 293, 299, 307, 311, 317, 325, 329, 331, 333, 343, 347, 349, 351}

For rectangles needing 14 squares, more than half the values have larger side 323 or 352.

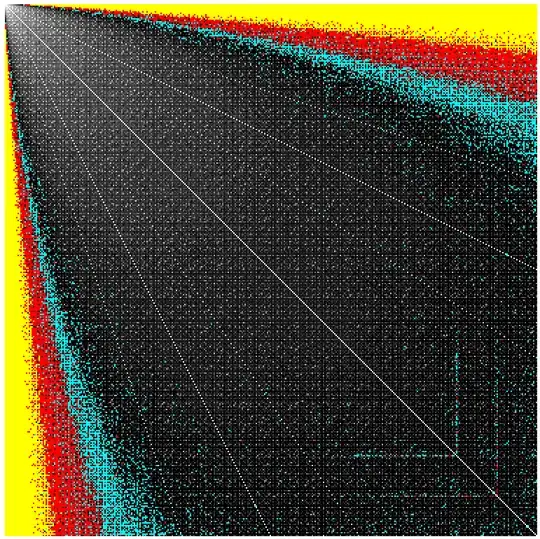

If f(a,b) is the minimal number of squares needed for an aXb rectangle, an array plot of those values looks like the following, with gray levels for 1 to 13 squares, cyan for 14 squares, red for 15-18 squares, and yellow for 19+ squares. The anomalies are at 323 and 352.

What is special about 323 (and 352) and squared rectangles?

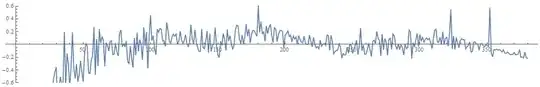

For rectangles with aspect ratios under 2 and relatively prime sides, calculate the average number of squares needed for a given longest edge. By the oblong conjecture, subtract (edge)^(1/3) +6. The last two spikes are at 323 and 352. The middle spike is at 180.

Where is the next hard value after 180, 323, 352?

UPDATE: As shown in the answer below, some better solutions exist for f(323,319). So it turns out there is nothing special about 323, it's just a runtime glitch of some sort on those two rows. Indeed, it turns out a 13 square solution exists for 323x319.