Proof is in the eye of the reader. A way I like to teach inductive proofs is to back up the inductive hypothesis by one, put the next item in it, then see if you match the claimed formula.

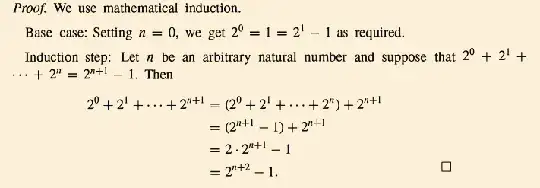

The base case is as described elsewhere: verify that the sum of $2^n$ is $2^{n+1}-1$ when $n=0.$ Tryng this out gives $1$ on the left and $1$ on the right, so the base case is legit.

The inductive hypothesis states that the sum of $2^i$ for $i=0, 1, 2, ...$ is $2^{n+1}-1$.

If that hypothesis is true at $n$, then it is also true at $n-1$. That is, it is assumed to be true, for the moment, at any value including $n-1$. If we believe this, then the sum up to $n-1$ is $2^{n-1+1}-1$.

Let's take that assumption and see what happens when we put the next item into it, that is, when we add $2^n$ into this assumed sum: $$2^{n-1+1}-1 + 2^n$$

$$= 2^{n} - 1 + 2^n$$by resolving the exponent in the left term, giving

$$= 2\cdot2^n - 1$$ because there are two $2^n$ terms. Finishing up,

$$= 2^1\cdot2^n - 1$$

$$= 2^{n+1} - 1$$by properties of exponents, giving us our claimed formula.

By adding the next term to the $n-1$ result, we get the claimed hypothesis, and therefore this pattern holds for any choice of $n$. Therefore, the hypothesis is true, and the presumed formula is correct.

Induction is a case of proof by "conveyor belt." You have an endless sequence of items starting at zero and your goal is to prove - by picking some arbitrary $n-1$ and $n$ somewhere along the way - that this formula holds as the sequence continues on forever. You use the sequence to help you verify the formula.