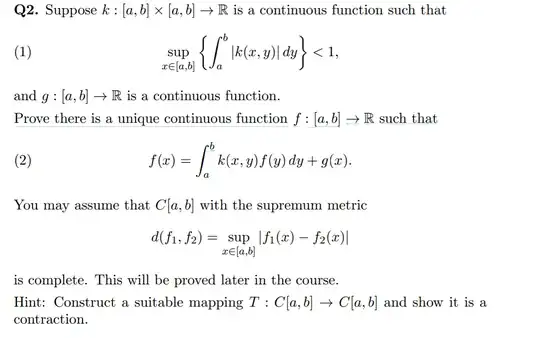

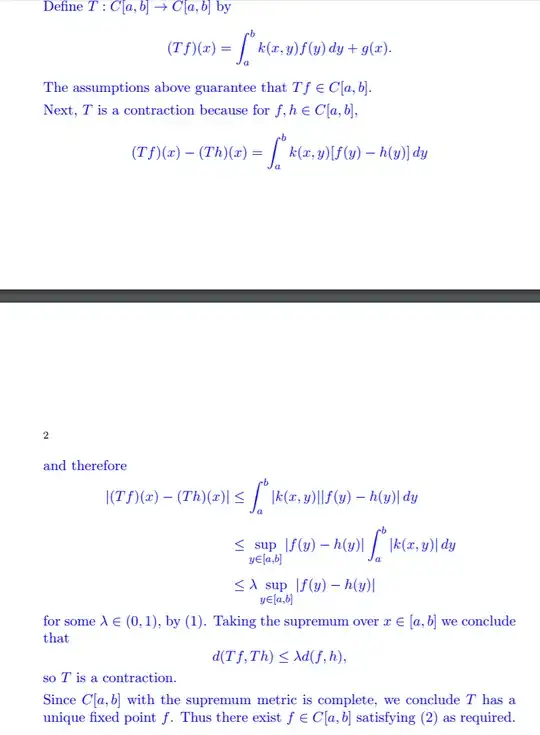

The above is the question, and here is a solution:

In the solution above, I do not quite understand:

Why the assumptions that $C[a,b]$ is complete with the sup metric guarentee that $Tf\in C[a,b]$?

Why do we say that $|(T f)(x) − (T h)(x)| ≤ \int^b_a |k(x, y)||f(y) − h(y)| dy$? I think it is $|(T f)(x) − (T h)(x)| = |\int^b_a k(x, y)[f(y) − h(y)] dy|= \int^b_a |k(x, y)||f(y) − h(y)| dy$. Is that correct?

Could someone please explain? Thanks!