(This answer is based on fleablood's answer and provides more details on how exactly to compute the result. Also, I have renamed some variables from the question to make the answer IMO easier to follow in isolation but hopefully the mapping is clear.)

Math

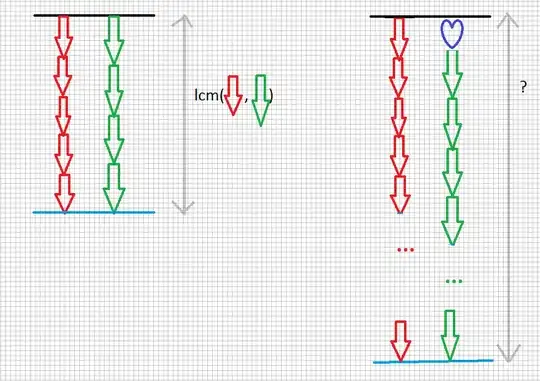

Assume that we have two periodic systems $A$ and $B$ with periods $p_A$, $p_B$ and phases $\phi_A$, $\phi_B$.

I found that it was mathematically simplest to take "phase" to mean the number of steps past the most recent reference point.

So in the question: steps are y-axis ticks, the arrow lengths are the periods, the ends of the arrows are reference points, and the phase of the second arrow is the negative advantage (since advantage measures steps-to-go from the origin to the next reference point rather than steps completed so far).

It takes time $p_A - \phi_A$ to visit the reference point of $A$ for the first time and additional time $p_A$ after that.

So the time after visiting the reference point of $A$ $m$ times is $m \cdot p_A - \phi_A$.

We want to find a time where $A$ and $B$ are both at their reference points, so we want $m$, $n$ such that $m \cdot p_A - \phi_A = n \cdot p_B - \phi_B$.

We don't have to worry about this being non-negative or minimal because we know that the combined period of $(A, B)$ is $p_C = \mathrm{lcm}(p_A, p_B)$ so we can just mod by that.

Rearrange this to get:

$$

m \cdot p_A - n\cdot p_B = \phi_A - \phi_B \tag{1}\label{1}

$$

Using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm, we can find values $s$, $t$ such that

$$

s \cdot p_A + t \cdot p_B = g \tag{2}\label{2} \\

\text{ where } g = \mathrm{gcd}(p_A, p_B)

$$

If $g$ does not divide $\phi_A - \phi_B$ then we cannot proceed: $A$ and $B$ will never land on their reference points at the same step. Otherwise, multiply (2) by $z = \frac{(\phi_A - \phi_B)}{g}$ to get (1) with $m = z \cdot s$ and $n = - z \cdot t$.

Therefore, $A$ and $B$ are both at the reference points at step $m \cdot p_A - \phi_A$. Take this mod $p_C$ to get the first positive time they coincide:

$$

x = (m \cdot p_A - \phi_A) \text{ mod } p_C

$$

or in terms of phases:

$$

\phi_C = (-m \cdot p_A + \phi_A) \text{ mod } p_C.

$$

Python Implementation

def combine_phased_rotations(a_period, a_phase, b_period, b_phase):

"""Combine two phased rotations into a single phased rotation

Returns: combined_period, combined_phase

The combined rotation is at its reference point if and only if both a and b

are at their reference points.

"""

gcd, s, t = extended_gcd(a_period, b_period)

phase_difference = a_phase - b_phase

pd_mult, pd_remainder = divmod(phase_difference, gcd)

if pd_remainder:

raise ValueError("Rotation reference points never synchronize.")

combined_period = a_period // gcd * b_period

combined_phase = (a_phase - s * pd_mult * a_period) % combined_period

return combined_period, combined_phase

def arrow_alignment(red_len, green_len, advantage):

"""Where the arrows first align, where green starts shifted by advantage"""

period, phase = combine_phased_rotations(

red_len, 0, green_len, -advantage % green_len

)

return -phase % period

def extended_gcd(a, b):

"""Extended Greatest Common Divisor Algorithm

Returns:

gcd: The greatest common divisor of a and b.

s, t: Coefficients such that s*a + t*b = gcd

Reference:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_Euclidean_algorithm#Pseudocode

"""

old_r, r = a, b

old_s, s = 1, 0

old_t, t = 0, 1

while r:

quotient, remainder = divmod(old_r, r)

old_r, r = r, remainder

old_s, s = s, old_s - quotient * s

old_t, t = t, old_t - quotient * t

return old_r, old_s, old_t

print(arrow_alignment(red_len=9, green_len=15, advantage=3)) # 18

print(arrow_alignment(red_len=30, green_len=38, advantage=6)) # 120

print(arrow_alignment(red_len=9, green_len=12, advantage=5)) # ValueError

Then the combination acts like another index-0 bus

---- What do you mean by this? I always took the lcm I calculated as period and the result of your formula (aka the meeting point) as offset/phase.

– atticus Dec 16 '20 at 21:30