Yes - actually, you have in $\mathbb{R}^n$ that all the norms are equivalent, that means, exists $a, b>0$ such that

$$ a|x|_1\leq |x|_2\leq b|x|_1 $$

This is the same as your neighborhood image - for every sphere (neighborhood using euclidean norm) you can place inside a cube (neighborhood using sup norm). This makes a lot (sadly, not all) of the theorems have very similar proofs when you change the norm.

For example, lets call $|\cdot|_1$ the sup norm, and $|\cdot |_2$ the euclidean norm. If we know that

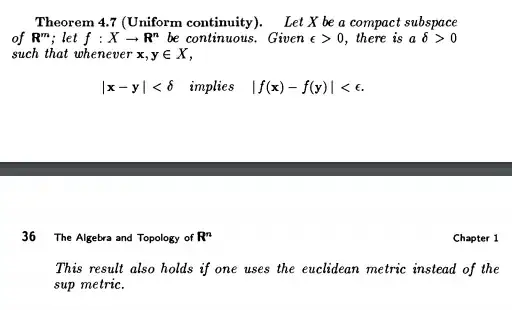

4.7-Sup: Let $X$ be a compact subspace of $\mathbb{R}^m$; let $f:X\to \mathbb{R^n}$ be continuous. Given $\varepsilon>0$, there is a $\delta>0$ such that whenever $x, y\in X$,

$$|x-y|_1<\delta \text{ implies } |f(x)-f(y)|_1<\varepsilon $$

Using that, we can prove the following theorem

4.7-Euc: Let $X$ be a compact subspace of $\mathbb{R}^m$; let $f:X\to \mathbb{R^n}$ be continuous. Given $\varepsilon>0$, there is a $\delta>0$ such that whenever $x, y\in X$,

$$|x-y|_2<\delta \text{ implies } |f(x)-f(y)|_2<\varepsilon $$

Proof: Recall that exists some (fixed) $a, b>0$ such that, for all $p\in \mathbb{R}^m$

$$a|p|_1\leq |p|_2 \leq b|p|_1$$

Let $\varepsilon>0$. We know that exists a $\eta>0$ such that, for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R^m}$

$$ |x-y|_1<\eta \text{ implies } |f(x)-f(y)|_1<\frac{\varepsilon}{b} $$

Now, if, $\eta> \frac{1}{b}|x-y|_2$, then $\eta>\frac{1}{a}|x-y|_2\geq |x-y|_1$, and then implies $\varepsilon>b|f(x)-f(y)|_1\geq |f(x)-f(y)|_1$. And calling $\delta=\eta b >0$, we have

$$ |x-y|_2<\delta \text{ implies } |f(x)-f(y)|_1<\varepsilon$$

So, 4.7-Sup implies 4.7-Euc.