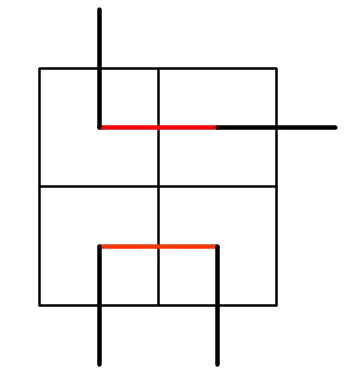

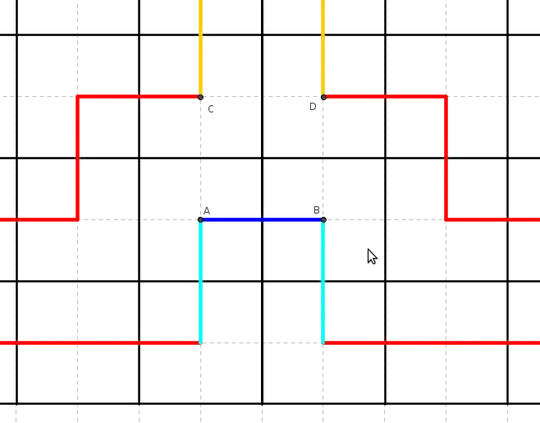

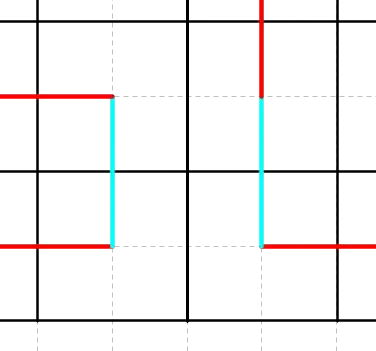

The idea from the link is correct. If we have some $2\times2$-subsquare with two parallel moves inside it (and no other moves inside it - remember about this), then we can change the two parallel moves into parallel moves in other direction and call it a swap. Here is a typical example:

Swap:

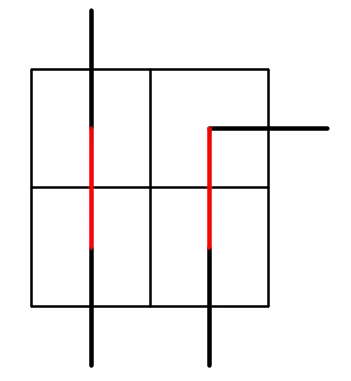

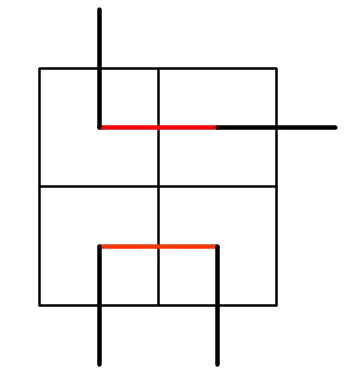

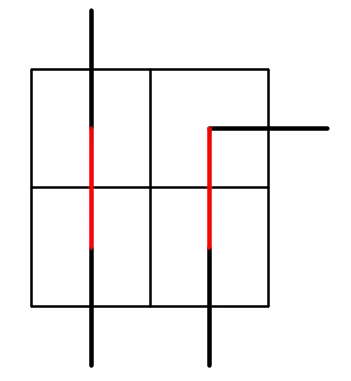

Swap:

One can prove that if we have some number of closed rook paths drawn on the board, then one swap always changes this number by 1 up or down, that is, changes parity. Indeed, let's think how the squares of the $2\times 2$ square where we make a swap can be connected from the the outside. WLOG, we can assume that swap changes 2 horizontal moves into 2 vertical. If the upper two squares are connected with each other from the outside, and the bottom two are connected from the outside, then we have two components affected under swap, and they become 1 component after the swap. If two right squares are connected and two left also, the situation is the opposite: we have 1 component with two red edges as in the picture before swap and 2 after the swap. There can never be a situation when upper left is connected with bottom right corner and upper right with bottom left. This is pretty obvious from the picture, but not so easy to prove formally: I'll add the details later, if you want.

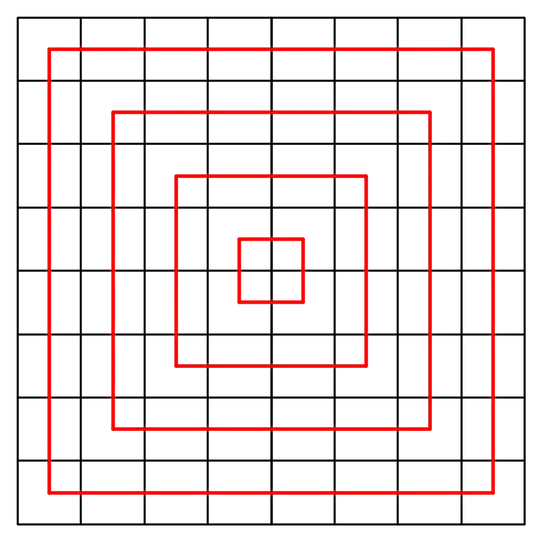

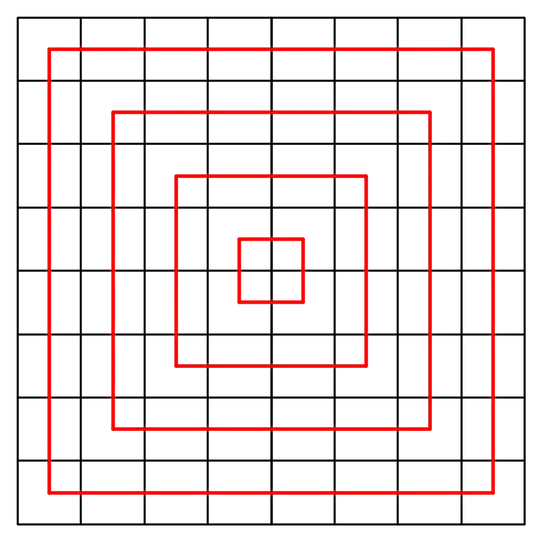

Now let us prove that any path can be reduced to the union of the following 4 paths by a series of swaps:

Why is this enough to disprove the existence of the path, described in the question? Obviously, we did an odd number of swaps, while reducing to this union of 4 paths, because each swap changed parity of the number of components, and initially there was the only one. However, this means that the number of swaps where we changed horizontal to vertical is not equal to the number of vice versa swaps. This means that we could not possibly preserve the property that the numbers of vertical and horizontal moves are the same, but in this union of 4 paths it is the same.

Why is this enough to disprove the existence of the path, described in the question? Obviously, we did an odd number of swaps, while reducing to this union of 4 paths, because each swap changed parity of the number of components, and initially there was the only one. However, this means that the number of swaps where we changed horizontal to vertical is not equal to the number of vice versa swaps. This means that we could not possibly preserve the property that the numbers of vertical and horizontal moves are the same, but in this union of 4 paths it is the same.

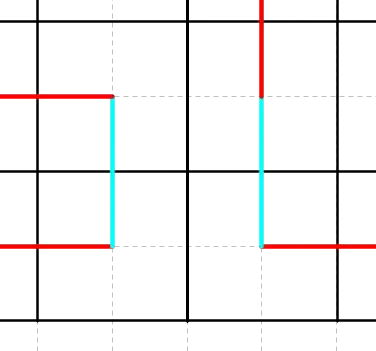

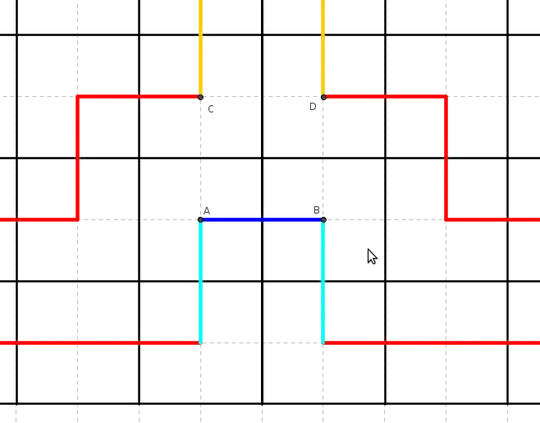

Now let us prove the main part: how we reduce any path to this union. We start to build firstly the outside layer, then after we done this, we can use similar method for inner $6\times 6$ square etc. Suppose in some moment the path along the border is not built: this means that there exist two neighbor squares at the border, not connected by a rook move:

Then we can swap two cyan edges and thus increase the number of edges along border by one. If we do this long enough, we eventually build the path along the border. However, there is an unpleasant case, where we can't do this:

If $A$ and $B$ are connected, we can't perform a swap. But if $C$ and $D$ are also connected, we can first make a swap in $ABCD$ square. Then $A$ and $B$ become disconnected, and we can swap two cyan moves. So the only bad case is when $C$ and $D$ are disconnected. Since they must be connected with two neighbor squares each, this means that the edges from them look like on the picture above. Then we can swap two orange edges and win... unless the two non-shown ends of the orange edges are also connected. Then move the picture two squares upper and repeat the argument until we hit the opposite side of the board. We obtain a structure where a lot of edges are known and there can be shown that this is impossible to continue it for covering the whole board by closed paths. I'll add technical details later.