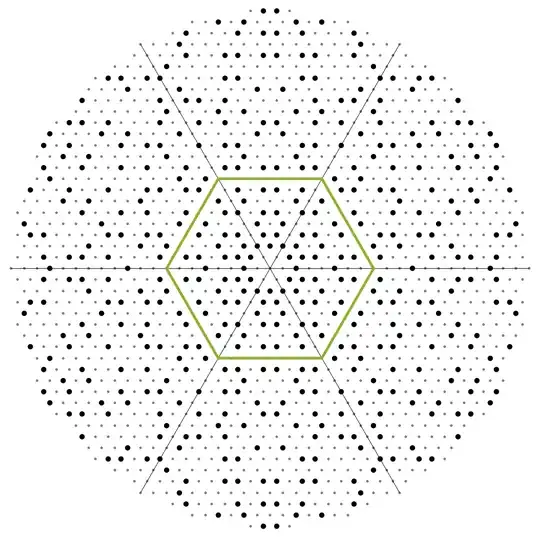

I recently played around with Eisenstein primes a bit (in an admittedly very amateurish way) and noticed among other things that there are no primes on the hexagonal ring that goes through (8,0) on the Eisenstein grid of the complex plane:

I thought this was a neat feature of the distribution of the primes and started looking for further such gaps. To my astonishment I haven't been able to find a single such gap up to at least a "radius" of 40,000,000. So now I'm wondering whether 8 is indeed the only such gap (ignoring the trivial cases of 0 and 1), or whether there might be further gaps at larger radii.

My Google efforts haven't turned up anything on this and I'm not sure how one would go about answering the question short of keeping the search running in hopes of finding another gap (which of course will never yield the answer "no further gaps exist"). I assume one could make a statistical argument based on the density of the Eisenstein primes, but I'm not sure how the prime number theorem applies to them.