It's something of a truism to say that inclusive definitions are better, because any properties proved of a more general category automatically apply to all special cases contained within it.

However, consider the following theorems:

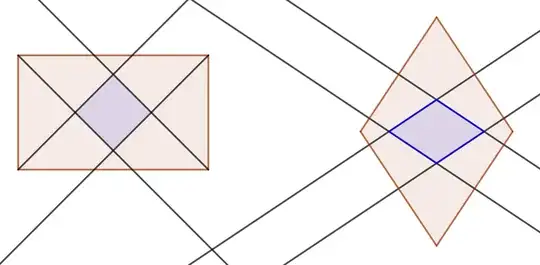

Theorem. The angle bisectors of any rectangle intersect at four points which form the vertices of a square.

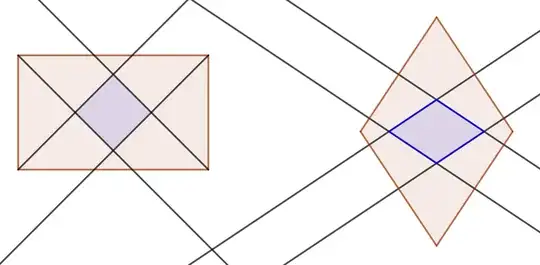

Theorem. The perpendicular bisectors of any rhombus intersect at four points which form the vertices of another rhombus.

(See Figures.)

These theorems are true statements if rectangle and rhombus are defined exclusively, i.e. if "rectangle" is defined as "a quadrilateral that is equiangular but not equilateral" and if "rhombus" is defined as "a quadrilateral that is equilateral but not equiangular". However, if inclusive definitions are used, these theorems are false, because if the rectangle (resp. rhombus) is a square, then the angle bisectors (resp. perpendicular bisectors) would be concurrent, and the "figure" formed by them would be a single point.

In other words: the theorems are true for the general category only if the more specific category is excluded. Depending on whether or not you think these theorems are things you want to be true in your theory, this could be a reason in support of adopting exclusive definitions.

There is another option, of course: one could define "rectangle" and "rhombus" inclusively, but in the statement of the theorem specify in the hypothesis that it is true of a non-square rectangle or a non-square rhombus. But if you have to do this often enough, at a certain point it might make sense to introduce a name for "non-square rectangle" and "non-square rhombus" -- and then we are right back to exclusive definitions again.

What about trapezoids, the topic the OP specifically asks about? As discussed in this answer, if trapezoids are defined exclusively, then it is possible to calculate the area of a trapezoid given only its four lengths (provided you know which ones are the parallel ones and which ones are the non-parallel ones). (Even if you do not know which sides are the parallel ones, you can determine that the area must be one of six uniquely determined possible values.) However, if trapezoid are defined inclusively, then the four lengths do not determine the area at all, as the area of a trapezoid with side lengths $a,b,a,b$ can take on any real value between $0$ and $ab$.

(Related: For historical background on when the "inclusive" definitions of quadrilaterals came to be standard, see also this answer on MESE.)