Let us write the equation as $$z^4-a^4=0$$ for some $a$ to be determined.

We can factor as

$$(z^4-a^4)=(z^2-a^2)(z^2+a^2)$$ and with a little more effort,

$$(z-a)(z+a)(z-ia)(z+ia).$$

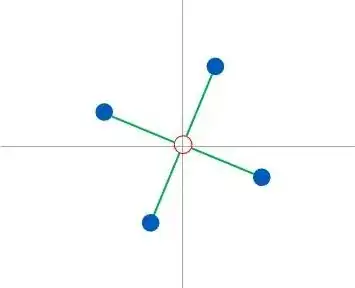

So the roots are of the form $a,ia,-a,-ia$, and we also have that $a^4=-i$. Without knowing how to extract the roots of a complex number, you can already write

$$(z-\sqrt[4]{-i})(z-i\sqrt[4]{-i})(z+\sqrt[4]{-i})(z+i\sqrt[4]{-i}).$$

To go further, you can use the polar form. Remember that the modulus of a product is the product of the moduli, and the argument of a product is the sum of the arguments.

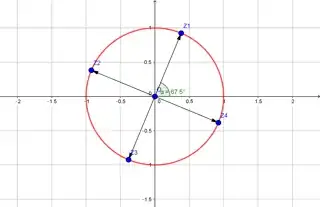

Then the modulus of a fourth power is the fourth power of the modulus ($-i\to1$ in our case) and the argument of a fourth power is four times the argument ($-i\to3\pi/2$).

Hence,

$$a=e^{i3\pi/8}.$$

You can also work this out directly, taking the square root twice.

$$(x+iy)^2=x^2-y^2+i2xy=-i$$

gives the system

$$x^2-y^2=0,\\2xy=-1.$$

Choosing $x=y$, we have the solution

$$\frac1{\sqrt2}(1-i).$$

Now let us solve

$$x^2-y^2=\frac1{\sqrt2},\\2xy=-\frac1{\sqrt2},$$ or after multiplication by $x^2$,

$$x^4-x^2y^2=\frac{x^2}{\sqrt2}$$ or

$$x^4-\frac{x^2}{\sqrt2}-\frac18=0.$$

One of the real solutions is

$$x=\frac12\sqrt{2+\sqrt2},$$ with $$y=-\frac1{\sqrt2\sqrt{2+\sqrt2}}=-\frac12\sqrt{2-\sqrt2}.$$

Solve. The format might look a bit strange but you can get it into format that you might expect (though, complicated) like so:FunctionExpand[ExpToTrig[z /. Solve[z^4 + I == 0, z]]]. Once you see that, you might try theExtensionoption ofFactor:Factor[z^4 + I, Extension -> {Sqrt[2 + Sqrt[2]]}]. – Mark McClure Jan 19 '17 at 16:43