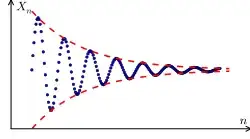

The important thing about a convergent sequence is that the convergent behavior has nothing to do with the first few terms; it doesn't have anything to do with the first hundred terms, or the first billion terms, or any given number of terms. The convergence is a property of the "tail".

The math is just saying (in technical language) what you intuitively know: that by going far enough out into the tail of the sequence, you can guarantee that EVERY TERM IN THE TAIL FROM THAT POINT ON is as close to the limit as you want.

How far do you need to go? Well, it depends on how close to the limit you want the tail to be. In fact, YOU don't get to choose that -- I get to say how close ("within $0.000001$") and then you have to go out into the tail and find a point where the entire rest of the tail is within MY SPECIFIED CLOSENESS of the limit. In a specific example, maybe you found that if you go out to the $537$th term, that term and all the terms after it are within $0.000001$ of the limit.

In the technical language of mathematics, I have specified a closeness (here, I said $\epsilon = 0.000001$, but it could have been any number, so we just call it $\epsilon$) and you have found a point in the tail (here, you found $N=537$) after which all subsequent terms (all $a_n$ for $n\geq N$) are within my specified closeness of the limit (that is, $|a_n-a|<\epsilon$ for all $n\geq N$). Remember, numbers are "close" if their difference is small in absolute value.

Now, how did I know $a$ was the limit? I didn't. It's the DEFINITION of being the limit if it has that property (if you can find the tail when I give the closeness, no matter what closeness I give). And if it happens that the "$a$" is NOT the limit, you will find that there is indeed a value of $\epsilon$ I could specify for which NO TAIL, no matter how far out, stays close to $a$. This could happen if either the sequence actually converges to some OTHER number, or doesn't converge at all.

Addendum: Since I'm the one that gave you $\epsilon$, and you still have to find an $N$ whenever I give you an $\epsilon$, we say "for all $\epsilon$" (and of course $\epsilon>0$; if $\epsilon=0$, then that would require a sequence for which the tail is eventually constant with every term equal to $a$, not very interesting).