If it was a pure mathematics, it would be OK. If it is kinematics, i.e. physics, it is absurd. In physics you need to track the physical quantities denoted by every expression and keep them consistent to make a reasonable calculations.

The expression $t^2$ is a physical quantity 'time squared', different from the acceleration's 'length divided by time squared'; the latter has an SI unit $m/s^2$ while the former is in $s^2$.

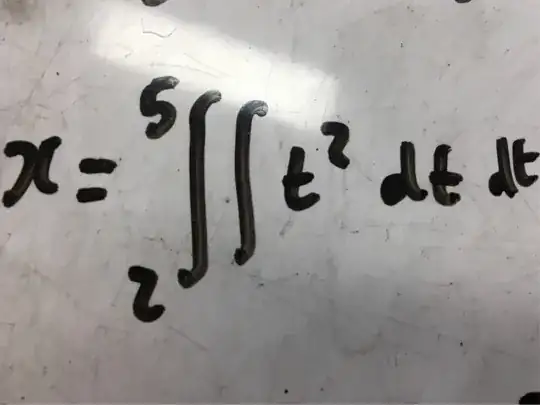

You need at least some constant $q$ in $m/(s^4)$ for a double integration $\int\int q t^2 \,dt\,dt$ to make any sense. And then, as others said, you need to carefully define limits of integration.

A distance $s$ travelled over time $T$ is an integral of a velocity over that time:

$$s(T) = \int\limits_{t=T_0}^T v(t)\,dt $$

and a final position is an initial position $x_0=x(T_0)$ plus the distance:

$$x(T) = x_0 + s(T)$$

Next, the velocity change over time follows from the acceleration, namely it's an integral of $a$:

$$v(t) = v_0 + \int\limits_{\tau=T_0}^t a(\tau)\,d\tau$$

where $v_0=v(T_0)$ is the initial velocity.

Now plug $v(t)$ into the first equation:

$$x(T) = x_0 + \int\limits_{t=T_0}^T \left(v_0 + \int\limits_{\tau=T_0}^t a(\tau)\,d\tau\right)\,dt $$

Add the acceleration definition and the integration expression is complete:

$$x(T) = x_0 + \int\limits_{t=T_0}^T \left(v_0 + \int\limits_{\tau=T_0}^t q\tau^2\,d\tau\right)\,dt $$

Work it from inside out:

$$\int q\tau^2\,d\tau = \frac 13 q\tau^3$$

so

$$v(t) = v_0 + \int\limits_{\tau=T_0}^t q\tau^2\,d\tau = v_0 + \left[\frac 13q\tau^3\right]_{\tau=T_0}^t = v_0 + \frac q3(t^3-{T_0}^3)$$

then

$$x(T) = x_0 + \int\limits_{t=T_0}^T \left(v_0 + \frac q3(t^3-{T_0}^3)\right)\,dt $$

$$= x_0 + \int\limits_{t=T_0}^T \left(v_0 + \frac q3 t^3- \frac q3 {T_0}^3\right)\,dt $$

$$= x_0 + \left[\frac q{12} t^4 + \left(v_0 - \frac q3 {T_0}^3\right)t\right]_{t=T_0}^T $$

$$= x_0 + \frac q{12} (T^4 - {T_0}^4) + \left(v_0 - \frac q3 {T_0}^3\right)(T-T_0) $$

Assuming your frame of reference has been chosen so that $x_0=0\,m$ and $v_0=0\,\frac ms$, the expression simplifies to

$$x(T) = \frac q{12} (T^4 - {T_0}^4) - \frac q3 {T_0}^3 (T-T_0) $$

For $T=5\,s$ and $T_0=2\,s$:

$$x(5\,s) = \frac q{12} ((5\,s)^4 - (2\,s)^4) - \frac q3 (2\,s)^3 (5\,s-2\,s) $$

$$ = \frac q{12} (625 - 16)s^4 - \frac q3 8\cdot 3\, s^4 $$

$$ = \left(\frac {625 - 16}{12} - 8\right)q\,s^4 $$

$$ = 42.75\, q\,s^4$$

If $q = 1\,\frac m{s^4}$, as I suppose from your attempt to write the double integral:

$$ x(5\,s) = 42.75\,m$$