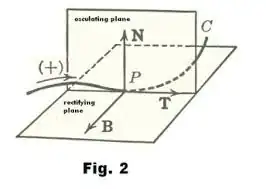

In studying calculus of space curves, we calculate the quantities "curvature" ($\kappa$) and "torsion"($\tau$). Both have inverse-length as units, so their reciprocals $\frac{1}{\kappa}$ and $\frac{1}{\tau}$ have units of length, and are called "radius of curvature" and "radius of torsion".

I understand that radius of curvature is the radius of a curve's osculating circle at a point. That's is a pretty clear notion geometrically, but I struggle to obtain a corresponding notion for radius of torsion.

Can anyone share a geometric intuition behind this length, and what it tells us about a non-planar curve? According to http://mathworld.wolfram.com/OsculatingSphere.html, the osculating sphere does not have radius $\frac{1}{\tau}$, so it's not that. Calling it a "radius" seems to imply that it's a radius of something.

Thanks in advance for any insight.

Edit: If a helix is given by $\left<a\cos t,a\sin t,bt\right>$, ($a$ and $b$ positive), then the curvature is $\frac{a}{a^2+b^2}$ and the torsion is $\frac{b}{a^2+b^2}$. There's a lovely duality there, and if you define a dual helix by swapping $a$ and $b$, then the curvature of one is the torsion of the other, and vice versa. Thus, we could say that the radius of torsion is the radius of curvature for a "dual" helix, but I hesitate to define a whole new kind of duality just to awkwardly impart meaning to a phrase I saw in a book. I don't know whether people who know a lot about helices think this way.

I'm still hoping there's a more natural answer out there.