I am wondering why Pascal's Theorem, as well as other 'Euclidean' results in projective geometry like Brianchon's Theorem should be true for not only circles, but also conics in general. Is there some sort of projective transformation that sends conics to circles, and how exactly does projective geometry present such a nice setting for conics in the Euclidean plane?

2 Answers

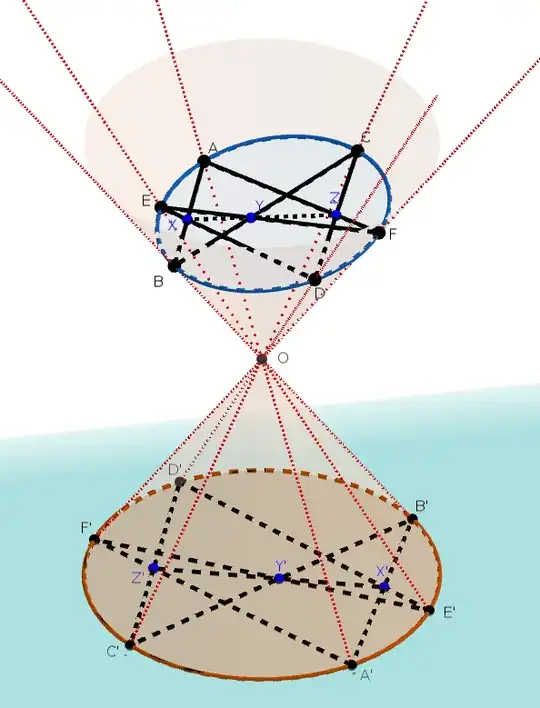

To provide such an intuitive explanation, I will prove Pascal's theorem and Brianchon's theorem for conics using a central projection (given that the theorems for circles are already proved)

Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a conic.

(i) (Pascal's theorem) $A, B, C, D, E, F$ are six points on $\mathcal{S}$ then the intersections of $AB$ and $DE$, $BC$ and $EF$, $CD$ and $FA$ are collinear.

(ii) (Brianchon's theorem) $a, b, c, d, e, f$ are six tangent lines of $\mathcal{S}$, then the following three lines are concurrent:

- the line through the intersections of $a, b$ and $d, e$

- the line through the intersections of $b, c$ and $e, f$

- the line through the intersections of $c, d$ and $f, a$

Proof of Pascal's theorem for conics

Let $X$ be the intersection point of $AB$ and $DE$, $Y$ be the intersection point of $BC$ and $EF$, $Z$ be the intersection point of $CD$ and $FA$. We will show that $X, Y, Z$ are collinear.

Because a conic is the intersection of a (circular) conical surface and a plane not passing through the cone point, there exists a (circular) conical surface $\mathcal{C}$ and a plane $\mathcal{P}$ such that the section of $\mathcal{C}$ with $\mathcal{P}$ is the conic $\mathcal{S}$.

Denote the cone point by $O$. Let $\mathcal{P'}$ be a plane that is perpendicular to the axis of the conical surface then the section of $\mathcal{C}$ by $\mathcal{P'}$ is a circle.

Consider the central projection $f_{O}: \mathcal{P}\to \mathcal{P'}$ that maps a point $M$ on $\mathcal{P}$ to the intersection point of $OM$ and $\mathcal{P'}$. Let $$f_{O}: A, B, C, D, E, F, X, Y, Z \mapsto A', B', C', D', E', F', X', Y', Z'$$

The inverse of $f_{O}$ is the central projection from $\mathcal{P'}$ onto $\mathcal{P}$ where the center of projection is still $O$.

Because central projections preserve collinearity, it follows that $A'B'$ intersects $D'E'$ at $X'$, $B'C'$ intersects $E'F'$ at $Y'$, and $C'D'$ intersects $F'A'$ at $Z'$. Due to Pascal's theorem for circles, $X', Y', Z'$ are collinear. Since central projections preserve collinearity, we conclude that $X, Y, Z$ are collinear.

The proof of Brianchon's theorem is similar. One can still use this central projection and the property that central projections preserve tangency.

- 2,159

In projective geometry, a circle is just a special case of a conic, namely one passing through the ideal circle points $(1,\pm i,0)$. So if you allow for complex transformations, then you can take a pair of conics and map two points of intersection to these special points to obtain a configuration with two circles. For more than two conics, though, this only holds true if all of the conics have two points of intersection (real or complex) in common.

A circle is a fundamentally Euclidean concept. Or perhaps I should say a metric-dependent object. In neutral projective geometry, with no points designated to play the role of the ideal circle points, you can't speak about circles but you can still speak about conics. For this reason, conics are the more natural objects in projective geometry. You will notice how a projective transformation tends to transform a circle to some non-circular conic in general.

The Euclidean plane is essentially the projective plane with the ideal circle points as distinguished points (and derived from them the line at infnity as a distinguished line). In the context of Cayley-Klein geometry one can distinguish any conic to introduce a metric on the projective plane. The pair of ideal circle points is a special degenerated conic, namely one where the primal representation describes the set of all points at infinity, as a line with multiplicity two, while the dual representation describes as tangents the set of all lines passing through either of these ideal circle points. But perhaps this is going way further than what you were actually asking.

- 44,006