I suppose that you are expected to use the argument principle. Let $\gamma$

be the curve

$$

\gamma: [0, 2 \pi] \to \Bbb C, \gamma(t) = e^{i t} \, .

$$

and $a \in \Bbb C$. If $f$ does not take the value $a$ on $|z|=1$

then the number of solutions to $f(z) - a = 0$ in $|z| < 1$ is

$$

N = \frac{1}{2\pi i} \int_{\gamma} \frac{f'(z)}{f(z)} \, dz

= \frac{1}{2\pi i}\int_{f \circ \gamma} \frac{dw}{w-a}

= \text{n}(f \circ \gamma, a)

$$

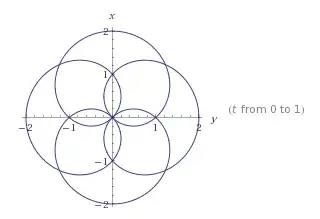

and that is the winding number of the curve $ \Gamma := f \circ \gamma$ with respect to $a$, and $\Gamma$ is exactly what you

plotted.

There is a simple method to determine the winding number $\text{n}(\Gamma, a)$ in each connected component of $G := \Bbb C \setminus |\Gamma|$ (see for example Determine the Winding Numbers of the Chinese Unicom Symbol): It is zero in the unbounded

component, and it changes by $+1$ or $-1$ when you cross $\Gamma$,

depending on the curve direction at the crossing:

From now on let us consider a real number $x \ge 0$ (the case $x \le 0$

is identical because $f(-z) = -f(z)$).

The argument principle gives us the following

number of solutions $N_{<}(x)$ of $f(z) = x$ with $|z|<1$:

$$

\begin{array}{l|c|c|c|c|c|c}

\mbox{} & x=0 & 0<x<1 & x=1 & 1<x<2 & x=2 & 2<x \\

N_{<}(x) & ? & 3 & ? & 1 & ? & 0 \\

\end{array}

$$

The argument principle is not directly applicable in the cases $x=0,1,2$.

I don't know what the most elegant way is to treat these special cases.

Here is one possible approach:

The number of solutions of $f(z) = x$ with $|z|=1$ can be read from the graph

of $\Gamma$ (how often does it pass through $x$), and the total number of solutions must be 5 (the degree of the

polynomial). This gives the following values for the

number of solutions $N_{<}(x)$, $N_{=}(x)$, $N_{>}(x)$ of $f(z)=x$ with $|z|<1$, $|z|=1$, or $|z|>1$,

respectively:

$$

\begin{array}{l|c|c|c|c|c|c}

\mbox{} & x=0 & 0<x<1 & x=1 & 1<x<2 & x=2 & 2<x \\

N_{<}(x) & ? & 3 & ? & 1 & ? & 0 \\

N_{=}(x) & 4 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

N_{>}(x) & ? & 2 & ? & 4 & ? & 5 \\

\end{array}

$$

$f(z) = 0$ has one solution in the unit circle ($z=0$).

The remaining unknowns can be determined using the fact that

the zeros of a polynomial depend continuously on the coefficients

(here: on $x$). For example, for $x > 2$, $f(z)=x$ has 5 solutions satisfying

$|z|>1$, therefore $f(z)=2$ must have at least 5 solutions satisfying

$|z| \ge 1$. But we already know that there is exactly one solution with

$|z|=1$. A similar reasoning can be applied at $x=1$.

This gives the complete picture:

$$

\begin{array}{l|c|c|c|c|c|c}

\mbox{} & x=0 & 0<x<1 & x=1 & 1<x<2 & x=2 & 2<x \\

N_{<}(x) & 1 & 3 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

N_{=}(x) & 4 & 0 & 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

N_{>}(x) & 0 & 2 & 2 & 4 & 4 & 5 \\

\end{array}

$$