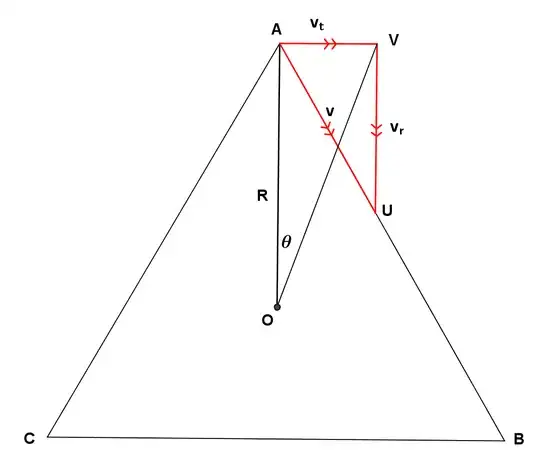

This question was suggested to be placed in the math forum. 3 particles are at the corners of an equilateral triangle with side $a$. Assume that particle 1 is at $(0,0)$, particle 2 is at $(a,0)$ and particle 3 is at $(a/2, a\sqrt 3/2)$. They all start moving simultaneously with a velocity $v$ constant in modulus, but with the first particle heading towards the second one, the second towards the third, and the third towards the first particle.

The typical question is how soon will they meet? I can easily answer this question with symmetry and relative speed considerations (they meet at the centroid after a time $2a/3v$). My question is a bit more complicated.

- Can we solve this without invoking symmetry, but purely mathematically?

- Second, can we describe the velocity vector of particle 1 as a function of time $t$ assuming it started at the origin?

- Third, can we describe the trajectory of particle 1 as a curve mathematically?