For a rectangle of size $m\times n$ with sizes being coprime:

- when a diagonal leaves the starting corner, it goes through the first square;

- and before it reaches the opposite corner it crosses $n-1$, say, horizontal lines of the grid, and $m-1$ vertical lines, each time entering a new square.

So the diagonal visits $m+n-1$ unit squares.

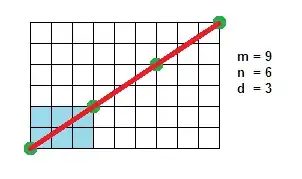

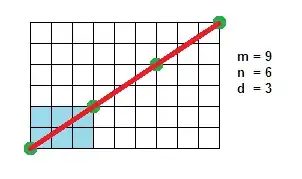

For sizes not coprime let $d = \gcd(m,n)$. Then we can reduce the problem to $d$ rectangles of size $\frac md\times\frac nd$ which makes a result of

$$d\cdot \left(\frac md + \frac nd - 1\right) = m + n - d$$

$$ = m + n - \gcd(m,n)$$

And we can see, that the former result is a special case of the latter: the 'minus one' term is a 'minus GCD of sizes', since a GCD of coprime numbers is $1$.