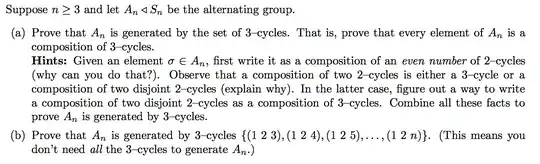

Even permutations (elements of $A_n$) are products of "pairs of transpositions". So it behooves us to examine what pairs of two arbitrary transpositions behave like.

Suppose our two transpositions both move (swap) the same two elements, that is we have:

$(a\ b)(a\ b) = e$.

Such a pair of adjacent transpositions, if they exist, can safely be cancelled, so we will worry about them no more.

One other possibility is our adjacent transpositions in a product share no common elements in their swaps-that is, they are disjoint, like:

$(a\ b)(c\ d)$.

We'll look at these later. Let's look at the only other possibility, that our pair of transpositions share exactly one common element they move, as in:

$(a\ b)(a\ c)$.

This is easily seen to be the $3$-cycle $(a\ c\ b)$.

So we have that any adjacent pair of transpositions reduces to either:

a) the identity

b) a disjoint pair of transpositions

c) a $3$-cycle.

So any element of $A_n$ can be written as a combination (product) of those $3$ possibilities above. Let's look more closely at option b):

Verify that $(a\ b\ c)(b\ c\ d) = (a\ b)(c\ d)$.

This shows any disjoint pair of transpositions can be written as a product of $3$-cycles, so any element of $A_n$ is a product of $3$-cycles, that is, the $3$-cycles generate $A_n$.

Note that we need $n \geq 4$ for this to work, however, for $n = 3$, the only elements of $A_3$ are the $3$-cycles and the identity, and for $n = 2$, we have $A_2 = \{e\}$, which is "vacuuously" generated by the non-existent $3$-cycles (similar considerations hold for $n = 1$, which is rarely considered as a permutation group since it has no transpositions at all).