Note that a thickened neighborhood of each $X_i$ for $i = 1,2$ open covers $X_1 \cup_f X_2$. Let the open cover we constructed be $\{U, V\}$. $U$ and $V$ deformation retracts to $X_1$ and $X_2$ respectively. Note that $U \cap V$ is the boundary torus of $X_i$, hence $i_U : \pi_1(U \cap V) \to \pi_1(U)$ takes the meridian to $0$ and longitude to $1$ and $i_V : \pi_1(U \cap V) \to \pi_1(V)$ takes the meridian to $1$ and longitude to $0$.

Hence, the relators make the generators vanish. Thus, by Siefert-van Kampen theorem, we conclude $\pi_1(X_1 \cup_f X_2) \cong 0$.

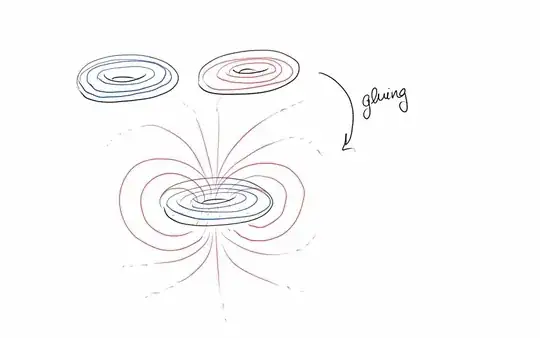

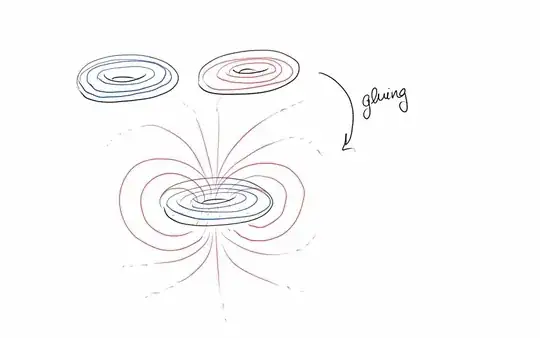

A straight-forward "cheat" to do these problems is to determine the homotopy type of the adjunction space. In this case, $X_1 \cup_f X_2$ is actually homeomorphic to $S^3$. To see this, consider a solid torus in $\Bbb R^3$. Take the complement. This also looks somewhat like a genus $1$ thing. Indeed, compactifying precisely gives you a torus. Thus, $S^3$ can be decomposed into two tori glued precisely by the homeomorphism you mention (you should be able to see this with some practice).

Here's a sketch to help you see this (from this answer) :

Thus, $\pi_1(X_1 \cup_f X_2) \cong \pi_1(S^3) \cong 0$.

As a side-note, decomposing $3$-manifolds into solid genus $g$ surfaces (usually called handlebodies) is called Heegaard decompositon for the $3$-manifold. It is known that every $3$-manifold admits a Heegaard decomposition. Thus, the problem of computing $\pi_1$ of $3$-manifolds in general becomes a problem of determining the homeomorphism by which the handlebodies are glued along.