This question has been successfully answered if you combine the other answers and the comment discussion that they contain. I will summarize:

There are various differences between the definitions. First is a technical one: May requires flatness of certain modules. Although this condition is technically important for some statements, it is inconsequential when it comes to the moral differences between the definitions. Anyway, you can (and should) ask about the difference over a field, where every module is flat.

Second, Hatcher asks that a Hopf algebra be connected. This condition allows him to drop any explicit reference to an antipode:

Proposition: Suppose that $H = \bigoplus_n H_n$ is a $\mathbb{Z}$-graded bialgebra over $R$, associative unital and coassociative counital, which is connected in the sense that $H_{<0} = 0$ and $H_0 = R$. Then $H$ has an antipode.

For later linguistic ease, I'll call the grading on $H$ the cohomological grading. But this is just a name.

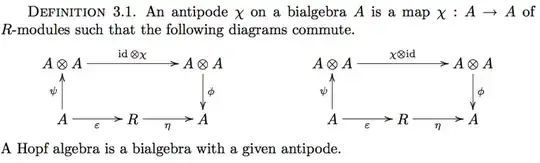

Recall that the multiplication $m$ and comultiplication $\Delta$ together supply a convolution product to $\operatorname{End}(H)$, given by $f \star g = m \circ (f \otimes g) \circ \Delta$, which is unital and associative if $H$ is both unital associative and counital coassociative. An antipode is a (two-sided) $\star$-inverse to the identity map. (In particular, the antipode is unique if it exists, so that it is a property, not structure, for a bialgebra to admit an antipode.)

Ben already supplied a link to a proof. But I want to present a proof strategy that is very general, and applies to lots of similar cases, because I think it is good to see it:

Proof: Let $I = \bigoplus_{n>0} H_n$. Since $H_{<0} = 0$, $I$ is both an ideal and a coideal, and so $H / I^m$ is Hopf. Moreover, since $I^m$ is supported in cohomoligcal degree $\geq m$, $H$ is isomorphic, as a cohomoligcally-graded bialgebra, to its $I$-adic completion:

$$ H \cong \varprojlim_{m \to \infty} H / I^m.$$

Let $\operatorname{gr}(H)$ denote the associated graded of the filtration $H \supset I \supset I^2 \supset \dots$. In other words,

$$ \operatorname{gr}(H) = \bigoplus_{m \geq 0} I^m / I^{m+1}.$$

This new grading is in addition to the cohomological grading. But I remark in passing that $I^m/I^{m+1}$ is supported in cohomological degree $\geq m$, and so $\operatorname{gr}(H)$ is also equal, as a cohomologically-graded object, to the infinite product $\prod_{m\geq 0} I^m/I^{m+1}$.

In any case, $\operatorname{gr}(H)$ is a bialgebra, generated as a ring by $I/I^2$. Just from considering degrees (with respect to the new grading), you see that for any generator $x \in I/I^2$, $\Delta x$ must be a linear combination of $x \otimes 1$ and $1 \otimes x$; from counitality, we must have $\Delta x = x \otimes 1 + 1 \otimes x$, or in other words $x$ is primitive. But then setting $S(x) = -x$ on the generators supplies an antipode.

Now the trick is to continuously interpolate between $H$ and $\operatorname{gr}(H)$. This trick goes under the name Rees. What I'll do is to introduce a new formal variable $\epsilon$. Now look at the sum

$$ X = H[\epsilon] \oplus I[\epsilon] \oplus I^2[\epsilon] \oplus \dots = \bigoplus_{m \geq 0} I^m[\epsilon]_m = \bigoplus_{m\geq 0} X_m,$$

where the subscript "$m$" just keeps track of which summand we are in. I remark in passing that, in the cohomologically-graded world, I can ignore whether this is an infinite sum or an infinite product, since the $m$th summand is supported in cohomological degrees $\geq m$. Now to this total sum $X$, I'll impose the following relation: for any $x \in X_m$, let me write $x_{m-1}$ for "the same" element thought of in $X_{m-1}$ (via the canonical map $X_m \hookrightarrow X_{m-1}$); now force $x_{m-1} \equiv \epsilon x$ for all $x \in X_m$.

I will call this quotient $\operatorname{Rees}(H)$. It is by construction an object over the polynomial ring $R[\epsilon]$. Note that:

$$ \operatorname{Rees}(H) / (\epsilon = 0) = \operatorname{gr}(H), \quad \operatorname{Rees}(H) / (\epsilon \neq 0) = H,$$

where by "$\epsilon \neq 0$" I mean for any invertible value of $\epsilon$.

Moreover, $\operatorname{Rees}(H)$ turns out to be a (cohomologically-graded) bialgebra over $R[\epsilon]$. The last step is then a rather standard application of the following idea (but translated into algebraic geometry): the existence of $S$ is the statement that something, somewhere, is invertible; but invertibility is an open condition; so, since $S$ exists when $\epsilon = 0$, it exists for $\epsilon$ sufficiently small; but there are small invertible numbers.

Ok, that wasn't a convincing paragraph except maybe when $R = \mathbb{R}$, and even then it's sketchy. But the real argument is essentially the same: you show from very abstract principles that the region where $S$ exists is an intersection of countably many Zariski-open subsets of $\operatorname{Spec}(R[\epsilon])$, and that this intersection contains $0$, but then this intersection contains an invertible value of $\epsilon$.

Let me make this argument completely explicit in the case when $R$ is a field. In this case, you can (arbitrarily) choose a splitting of the inclusion $I^{m+1} \subset I^m$, i.e. you can set $I^m \cong J_m \oplus I^{m+1}$. Having made these arbitrary choices, you find vector space isomorphisms $H \cong \bigoplus J_m \cong \operatorname{gr}(H)$.

These vector space isomorphisms also provide a vector space decomposition of the Rees algebra: as a vector space, $\operatorname{Rees}(H) \cong H[\epsilon ]\cong \operatorname{gr}(H)[\epsilon ]$. Moreover, the comultiplication and multiplication on $\operatorname{Rees}(H)$ differ from those on $\operatorname{gr}(H)[\epsilon ]$ by terms of order $\epsilon$. So you take the antipode $S_{\epsilon=0}$ on $\operatorname{gr}(H)$, and try to use it as an antipode for $\operatorname{Rees}(H)$, and calculate how far off you are, and you find: $S_{\epsilon=0} \star \operatorname{id} = 1_\star + \text{error}$, where $1_\star$ is the unit for the convolution product, and $\text{error}$ is of order $\epsilon$. But now you are in business, because $\star$ is bilinear, and so you how to invert things of the form $1 + O(\epsilon)$:

$$ (1_\star + \text{error})^{-1} = 1 - \text{error} + \text{error}^2 - \text{error}^3 + \dots.$$

And the true antipode would be

$$S_\epsilon = (1 + \text{error})^{-1} \star S_{\epsilon=0}.$$

Well, this would work as soon as this power series converges. This is where I come back to my constant refrain that I can ignore the difference between sums and products. See, in addition to being order $\epsilon$, the error term also strictly-raises the (noncohomological) degree. So the sum converges if you think of it as a map from the infinite sum to the infinite product. $\Box$

There is one more difference between the two proposed definitions of "Hopf algebra": May (and Wikipedia) requires a Hopf algebra to be coassociative, and Hatcher does not.

This is a nontrivial difference, as pointed out by darij grinberg.

Counterexample: Consider a polynomial ring $H = R[h_1, h_2, h_3]$, in which the generator $h_i$ is in degree $i$ (and I'm not doing any Koszul signs, I just mean a totally-bosonic ordinary polynomial ring; so if you want, place $h_i$ instead in degree $2i$). Counitality and degree considerations force:

$$ \Delta h_1 = h_1 \otimes 1 + 1 \otimes h_1,$$

$$ \Delta h_2 = h_2 \otimes 1 + 1 \otimes h_2 + \alpha h_1 \otimes h_1,$$

$$ \Delta h_3 = h_3 \otimes 1 + 1 \otimes h_3 + \beta h_2 \otimes h_1 + \gamma h_1 \otimes h_2,$$

for some constants $\alpha,\beta,\gamma \in R$.

Slightly remarkably, for any $\alpha$, the subalgebra $R[h_1,h_2]$ is coassociative. However:

$$ (\Delta \otimes \operatorname{id})\Delta h_3 - (\operatorname{id} \otimes \Delta)\Delta h_3 = \alpha(\beta -\gamma) h_1 \otimes h_1 \otimes h_1.$$

So this is coassociative iff $\alpha(\beta -\gamma) = 0$.