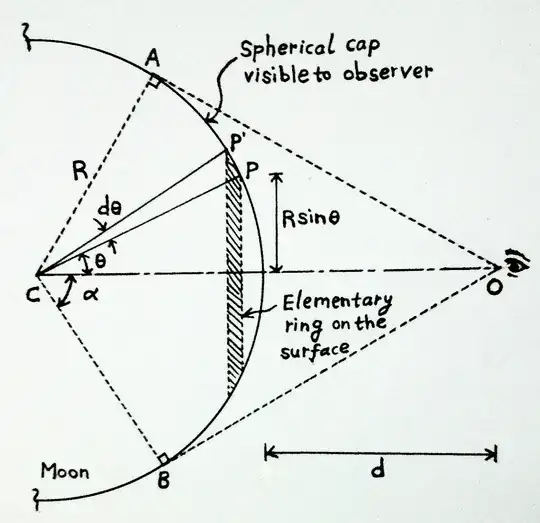

Let's assume you're looking from above, so that you see a region of the sphere that looks like the arctic --everything above some latitude line $y = c$ (which constitutes a circle on the sphere itself). The area of this "cap" region is $2\pi R (R - c)$ (See below).

So the only question is "what's $c$?" From the earth's center to the eye to a point on the circle-of-latitude is a right triangle; the short leg is $R$, the hypotenuse is $R + d$, so the long leg is

$$

a = \sqrt{ (R+d)^2 - R^2 }

$$

The angle at the earth's center is then $\theta = \arccos(\frac{R}{R+d})$, so the $y$-coordinate of the latitude line is $R$ times the cosine of that angle, i.e.,

$$

c = R\cos\left(\arccos\frac R{R+d}\right) = \frac{R^2}{R+d},

$$

and the area is

\begin{align}

2\pi R (R - c)

&= 2\pi R \left(R - \frac{R^2}{R+d}\right) \\

&= 2\pi R\frac{R(R+d)-R^2}{R+d}\\

&= 2\pi R\frac{Rd}{R+d}\\

&= 2\pi R^2\frac d{R+d}\\

\end{align}

Reason for the area claim above: the map that projects a point $(x, y, z)$ of a sphere to the point $(x/R, y, z/R)$ of the circumscribed cylinder, where $R = \sqrt{x^2 + z^2}$, has a derivative whose determinant is 1, so it's area preserving. So the area of a cap of the sphere above height $c$ is the same as the area of a slice of a cylinder above height $c$, namely $2\pi R (R - c)$.