Recently I was studying a linear algebra class which introduce some basic concepts of fields, groups

Once again I tried to divide by zero by constructing an algebraic structure from scratch using just a few axioms because I stumbled across this when browsing the site

We knew that the important theorem in fields that

$$0\cdot n=0$$

holds for all n

and one of the shortest proof of this is as follows

$$\text{Take any }a \in S$$ $$a\cdot 0=a\cdot (0+0) \text{ (Additive identity)}$$ $$a\cdot 0=a\cdot 0+a\cdot 0 \text{ (Distributivity of }\cdot n\text{ over }+)$$ $$a\cdot 0=0 \text{ (Cancellation using additive inverses of }a\cdot 0) $$ $$\square$$

In my following attempt, I have not assumed anything for this set $S$ except

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Associativity} \\ \text{Additive and multiplicative identities}\\ \text{Multiplicative inverses}\\ \text{Distributivity} \end{matrix}$$ and the following was set as an axiom inspired from the link

$$0\cdot m=n \text{ (Call it "Zero axiom") }$$

The following 13 Theorems was then obtained (in order) from $S$ after some algebra

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 0.1,0.2,0.3} \\ 0 =n\cdot m^{-1} \\ n^{-1}\cdot 0=m \\m\cdot n \cdot m^{-1}=m \cdot 0 \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 1} \\ m+n=m \\ \text{Proof: } m=1 \cdot m=(1+0)\cdot m=m+0\cdot m=m+n \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 2} \\ n+n=n \\ \text{Proof: } n+n=(0 \cdot m)+(0 \cdot m)=(0+0)\cdot m=0\cdot m=n \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 3} \\ n+m=m \\ \text{Proof: } n+m=(0 \cdot m)+m=(0+1)\cdot m=1\cdot m=m \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 4} \\ m=m+1 \\ \text{Proof: } n\cdot m=(n+0) \cdot m=n\cdot m+0\cdot m=n\cdot m+n=n\cdot (m+1)\Rightarrow m=m+1 \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 5} \\ 1=1+m^{-1} \\ \text{Proof: } m\cdot n=m \cdot (n+0)=m\cdot n+m\cdot 0=m\cdot n+m\cdot n\cdot m^{-1}=m\cdot n \cdot (1+ m^{-1})\Rightarrow 1=1+m^{-1} \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 6} \\ (1+n^{-1})\cdot 0=m^{-1} \\ \text{Proof: } (1+n^{-1})\cdot 0=0+ n^{-1}\cdot 0=n^{-1}\cdot 0=m^{-1} \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 7} \\ n\cdot 0=0 \\ \text{Proof: Multiply n on the left both sides of Theorem 6 and then use Theorem 0.1} \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 8} \\ n\cdot n=n \\ \text{Proof: Using Theorem 7, } n\cdot n=n \cdot (0 \cdot m)=(n \cdot 0)\cdot m=0 \cdot m=n \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 9} \\ m^{-1}=0 \\ \text{Proof: Apply Theorem 7 to Theorem 0.2} \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 10} \\ n=1 \\ \text{Proof: Multiply m on the right both sides of Theorem 9 and then use the Zero Axiom} \\ \text{and multiplicative inverse property}. m\cdot m^{-1}=1 \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 11} \\ 1+1=1 \\ \text{Proof: Apply Theorem 10 to the Zero Axiom followed by} \\ \text{Theorem 9 to obtain } \\1=0\cdot m=(0+0) \cdot m=0\cdot m + 0\cdot m=m^{-1} \cdot m+m^{-1} \cdot m=1+1 \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 12} \\ m+m=m \\ \text{Proof: Factor out m and then apply Theorem 11} \end{matrix}$$

$$\begin{matrix} \text{Theorem 13} \\ 1+m=m \\ \text{Proof: Apply Theorem 10 to the Zero Axiom and then factor out m to obtain}\\ 1+m=0\cdot m+m=(0+1)\cdot m=1\cdot m=m \end{matrix}$$

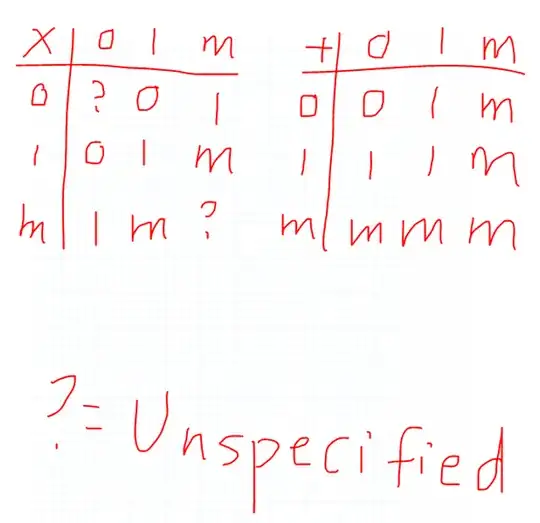

Sumarise all the findings in a Caley table we get the following:

Now since m remains unspecified by the axioms of $S$, if $m=0$ then we got a contradiction in Theorem 1 and Theorem 4

$$\begin{matrix} \color{red}{\text{Theorem 1 & 4} \\ 0+1=0\Rightarrow 1=0 \\ 0=0+1\Rightarrow 1=0 }\end{matrix}$$

However I don't understand, $\square$ was never proven in $S$ due to lack of additive inverses to apply cancellation property (and $S$ is possibly non integral domain, because $m \cdot m$ is unspecified and can be set to $0$ thus cancellation may not work in $S$).

But the contradictions of S clearly suggests that $\square$ must still be able to be proved in $S$ even without the cancellation law

Question:Why $$0\cdot 0=1$$ is not allowed, even if we lacked the cancellation law in this set to prove that $\square$ holds for all elements?