The simplest way of solving this equation is the method based on DeMoivre's Formula that Lab Bhattacharjee outlined.

That said, you can make your method work. You found the roots $z \pm i$ by setting the factor $z^2 + 1$ equal to zero. As Rasolnikov and 5xum noted, you should have obtained

$$z^2 = \frac{1 \pm \sqrt{-3}}{2}$$

when you set the factor $z^4 - z^2 + 1$ equal to zero.

Let $z = a + bi$, with $a, b \in \mathbb{R}$. Then

\begin{align*}

z^2 & = \frac{1 \pm i\sqrt{3}}{2}\\

(a + bi)^2 & = \frac{1 \pm i\sqrt{3}}{2}\\

a^2 + 2abi - b^2 & = \frac{1 \pm i\sqrt{3}}{2}

\end{align*}

Equating real and imaginary parts yields

\begin{align*}

a^2 - b^2 & = \frac{1}{2}\tag{1}\\

2ab & = \pm\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\tag{2}

\end{align*}

Solving equation 2 for $b$ yields

$$b = \frac{\pm\sqrt{3}}{4a}\tag{3}$$

Substituting this expression in equation 1 yields

\begin{align*}

a^2 - \frac{3}{16a^2} & = \frac{1}{2}\\

16a^4 - 3 & = 8a^2\\

16a^4 - 8a^2 & = 3\\

16a^4 - 8a^2 + 1 & = 4 && \text{complete the square}\\

(4a^2 - 1)^2 & = 4\\

4a^2 - 1 & = \pm 2\\

4a^2 & = 3 && \text{since $a \in \mathbb{R}$}\\

a^2 & = \frac{3}{4}\\

a & = \pm \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}

\end{align*}

Substituting this expression into equation 3 yields the four roots

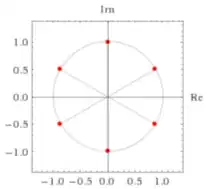

$$z = \pm\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \pm \frac{1}{2}i$$

of the equation $z^4 - z^2 + 1 = 0$. As you can check, these roots correspond to the values $n = 0, 2, 3, 5$ in the formula Lab provided.