Yes, if the middle row is a complex, then it will be exact. This is mentioned at the nlab. It seems to be a consequence of Bergman's salamander lemma. A direct proof is also possible:

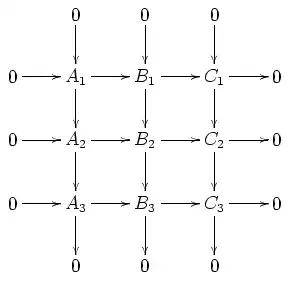

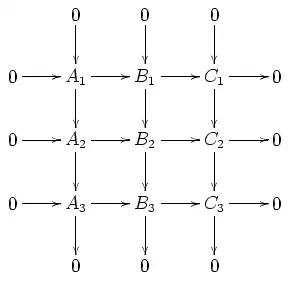

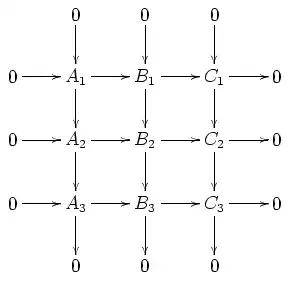

Let the columns be exact and the first and third row be exact, and assume that $A_2 \to C_2$ is zero. We prove that $0 \to A_2 \to B_2 \to C_2 \to 0$ is exact. (I suggest the reader to move the mouse over the diagram while following the proof.)

1) $A_2 \to B_2$ is monic: If $a_2 \in A_2$ maps to $0 \in B_2$, it also maps to $0 \in B_3$. Since $A_3 \to B_3$ is monic, the image in $A_3$ will also be $0$. Hence, there is a preimage $a_1 \in A_1$ of $a_2 \in A_2$. Look at its image $b_1 \in B_1$. Since it maps to $0 \in B_2$ and $B_1 \to B_2$ is monic, it follows $b_1=0$. Since $A_1 \to B_1$ is monic, it follows $a_1=0$, hence $a_2=0$. $\square$

2) $B_2 \to C_2$ is epic: This follows from 1) (generalized to abelian categories as usual) by duality. A diagram chase is also possible, but a little bit longer. $\square$

3) $\ker(B_2 \to C_2) = \mathrm{im}(A_2 \to B_2)$: We have $\supseteq$ by assumption that $A_2 \to C_2$ is zero. Conversely, let $b_2 \in \ker(B_2 \to C_2)$. Consider the image $b_3 \in B_3$. It maps to $0 \in C_3$, hence has a preimage $a_3 \in A_3$. Choose a preimage $a_2 \in A_2$ and look at its image $b'_2 \in B_2$. Then $b_2-b'_2$ maps to $0 \in B_3$, hence we find a preimage $b_1 \in B_1$. Notice that $b_2-b'_2$ maps to $0 \in C_2$ (in fact, $b'_2$ does since $A_2 \to C_2$ is zero). It follows that $b_1$ maps to $0 \in C_1$, hence it has a preimage $a_1 \in A_1$. Let $a'_2 \in A_2$ be its image. It maps to $b_2-b'_2 \in B_2$, so that $a'_2+a_2$ maps to $(b_2-b'_2)+b'_2=b_2$. $\square$

Without the assumption that $A_2 \to C_2$ is zero, we cannot conclude that the middle row is exact. Even in the case that each column is split exact. So let us assume $A_2=A_1 \oplus A_3$, $B_2=B_1 \oplus B_3$, $C_2 = C_1 \oplus C_3$ and that the columns are the canonical ones. Then $A_2 \to B_2$ may be written as a matrix $\begin{pmatrix} A_1 \to B_1 & A_3 \to B_1 \\ A_1 \to B_3 & A_3 \to B_3 \end{pmatrix}$ and similarly $B_2 \to C_2$ can be written as a matrix $\begin{pmatrix} B_1 \to C_1 & B_3 \to C_1 \\ B_1 \to C_3 & B_3 \to C_3 \end{pmatrix}$. Even though the product of the two upper (lower) diagonal entries is zero, the product of the matrices doesn't have to be zero. There are mixed terms such as $A_1 \to B_3 \to C_1$, and it should be easy to write down specific examples, say of vector spaces.

Finally, let me mention that diagram lemmas "should" be really seen as statements about complexes (or double complexes), not about commutative diagrams. Therefore, it is not "bad" that the "middle nine-lemma" "only" works for double complexes.