I would like to know if there is a rule to prove this. For example, if I use the distributive law I will get only $(A \lor A) \land (A \lor \neg B)$.

11 Answers

I find pictures are great for anything simple enough to use them, which this is.

Remember:

AND means the area taken up by both things. So the middle one is what is taken up outside B, but also inside A. Their junction is not counted because it is inside A but not outside B.

OR means it is covered by either one or both. Both of them cover the part of A that is outside B, and the junction is covered by A (first picture) so it is counted too. All in all, you just have A again.

Sorry if this is too simplistic, not sure what level you are at.

- 371

- 2

- 18

- 511

- 3

- 5

There are many ways to see this. One is a truth table. Another is to use the distributive rule: $$ A \lor (A \land \lnot B) = (A \land \top) \lor (A \land \lnot B) = A \land (\top \lor \lnot B) = A \land \top = A. $$

- 280,205

- 27

- 317

- 514

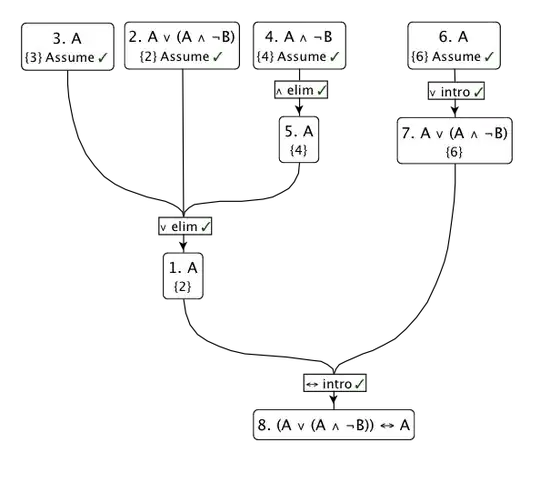

I would use my least favourite inference rule: Disjunction Elimination. Basically, it says that if $R$ follows from $P$, and $R$ follows from $Q$, then $R$ must be true if $P \vee Q$: $$(P \to R), (Q \to R), (P \lor Q) \vdash R$$

So let's assume $A \lor (A \land \neg B)$. Set $P = A$, $Q = A \land \neg B$, $R = A$ and apply the rule:

- If $P$ ($= A$) we are done.

- If $Q = A \land \neg B$ then $A$ (by conjunction elimination, $S \land T \vdash S$)

- By disjunction elimination $A \lor (A \land \neg B) \to A$.

The inverse is trivial: assume $A$, then by one of the variants of conjunction introduction ($S \vdash S \lor T$ for any $T$) $A \to A \lor (\cdots)$.

Here is a diagram of this proof:

- 371

- 2

- 18

- 203

- 1

- 5

Note that, when we know that $C$ implies $D$, we have $C \lor D = D$. This is analogous to taking the union of a set (corresponding to $D$) and one of its subsets ($C$): we get the largest set ($D$) back.

In your case, $C = A \land \lnot B$ and $D = A$, and the implication trivially holds.

- 14,704

- 1

- 31

- 40

A more intuitive look:

A is always true when A is true.

A & -B is only true when A is true.

Intuitively, applying OR to these two would produce a result C which is always true when A is true. As such, C is always true when A is true.

(Stop reading here if this explanation works for you.)

This is how I think about this problem. However, this explanation is not complete since all we've shown is that A -> C and not A <-> C.

So, let's also also show that C -> A.

A is always false when A is false.

A & -B is always false when A is false.

Intuitively, applying OR to these two would produce a result C which is always false when A is false. As such, C is always false when A is false; -A -> -C, which is the same thing as C -> A.

So A -> C and C -> A, so A <-> C.

- 133

- 4

Sometimes, people are confused by the letters. People like food, because it's easy to think about.

Pretend I ask you to flip a coin to choose between one OR the other of the following two options:

- An Apple, OR...

- An Apple, and definitely no Banana.

[The first is equal to "A", the second "A and not B". But don't think of the letters. Think about the apple, and the whether you also get a banana.]

That first one really means "An apple fersure, and maybe you'll get a banana."

So leaving something out is the same as saying "maybe".

Looking at them as a pair, whichever you get, there's definitely going to be an Apple involved. Yay. And if your coinflip picks the right one, you might get a Banana.

But isn't that the same as saying "maybe you'll get a Banana"? Just, with half the likelihood?

So all you can definitely logically say is, you'll get an Apple. You can't say anything about whether you'll get a Banana.

- 200

- 2

- 6

Similar to answer of Yuval Filmus. Using boolean algebra, in engineering notaion, and factoring (or factorising) out A.

$A+A\cdot\bar B=A\cdot(1+\bar B)=A\cdot1=A$

- 131

- 3

It seems as though no one mentioned it yet so I will go ahead.

The law to deal with these kinds of problems is the absorption law it states that p v (p ^ q) = p and also that p ^ (p v q) = p. If you try to use distributive law on this it will keep you going in circles forever:

(A v A) ^ (A v ~B) = A ^ (A v ~B) = (A ^ A) v (A ^ ~B) = A v (A ^ ~B) = (A v A) ^ (A v ~B)

I used the wrong symbol for not and equals but the point here is that when you are going in circles / when there is an and-or mismatch usually you should look to the absoprtion law.

B is irrelevant to the outcome as you will notice if putting this in a truth table.

- 31

- 1

Another intuitive way to look at this:

If A is a set, then we can say any given object is either (in A) or (not in A).

Now look at S = A or (A and not B):

If an object is in A, then "A or anything" contains all elements in A, so the object will also be in S.

If an object isn't in A, then "A and anything" excludes all elements not in A, so the object is neither in A nor in (A and not B), so it isn't in S.

So the outcome is that any object in A is in S, and any object not in A isn't in S. So intuitively, the objects in S must be exactly those in A, and no other objects.

When two sets have identical elements, they are defined to be the same set. So A = S.

- 121

- 3

A simple method you can always use if you're stuck is case analysis.

Assume $A$ is true. In that case the left side is true, because true OR anything is true.

Assume $A$ is false. False AND anything is false. False OR false is false.

Since $A$ can have no more possible values, you've proven the proposition.

- 233

- 1

- 4

lets consider:

1) A as 1 and B as 0.

2) A as 0 and B as 1.

3) A as 1 and B as 1.

4) A as 0 and B as 0.

using the first scenario : A or (A and !B) => 1 or ( 1 and 1) => 1 0r 1 => 1

using the second scenario: A or (A and !B) => 0 or ( 0 and 0) => 0 or 0 => 0

using the third scenario : A or (A and !B) => 1 or ( 1 and 0) => 1 or 0 => 1

using the fourth scenario: A or (A and !B) => 0 or ( 0 and 1) => 0 or 0 => 0

From the above four cases, the result always depends on A not on B, so the result is A.