No, you are confused.

Turing machines and Hypercomputation are both mathematical models, and they are both consistent because we can build mathematical models in which all functions are Turing computable, as well as models in which hypercomputable functions exist. These are of course different models. There is no mystery about having a lot of mathematical models of various theories, for instance, there are models of both euclidean and non-euclidean geometry.

The mathematical theory of computation should not be confused with "the real world". This is a bad thing to do because Turing machines are a piece of mathematics. Do you also think that infinite straight thin lines really exist in the physical world? Or maybe that they are slightly bent because of gravity?

Church's thesis is a piece of premathematical or philosophycal analysis which essentially says "Turing's mathematical definition of computation correctly models what can actually be computed in the real world". This is not a mathematical statement.

In one of the comments you made the following faulty line of reasoning: "... that imaginary worlds are from our mind and, since our brain is physical, that imaginary worlds are part of the physical world." To see why this makes no sense, consider a similar line of reasoning: "Yesterday I imagined a fairy with golden wings, and since the fairy was in my mind, and my brain is physical, the fairy is part of the physical world". The problem is that you are confusing the thoughts in your mind with their physical representation (the electro-chemical functioning of your brain).

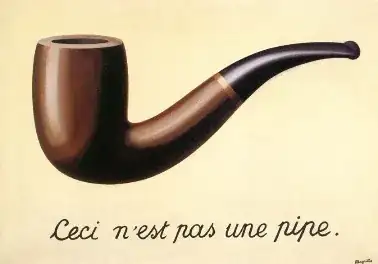

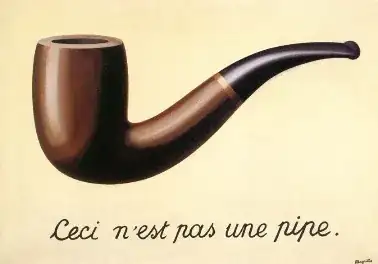

A Belgian artist put it very eloquently: