As the comments say, in the worst case you end up traversing the whole graph.

No matter what graph you have, breadth first search is always O(V + E).

So it's better to start with O(V + E) and see how we end up with O(b^d)

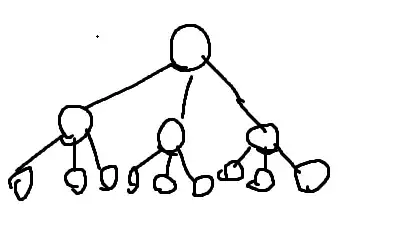

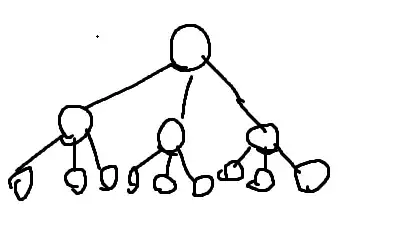

Specifically, in a basic example, the equation b^d is usually used for a tree, where every vertex branches out to b other vertices. With d layers to the tree.

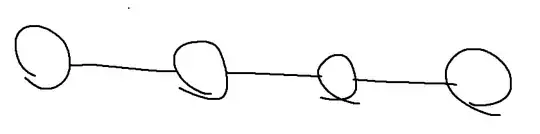

I'll use a 3^2 tree for it. 2 steps, with 1 vertex leading to 3 new vertices.

But there aren't 3^2 vertices, and there aren't 3^3 vertices.

There are V = 3^0 + 3^1 + 3^2 vertices.

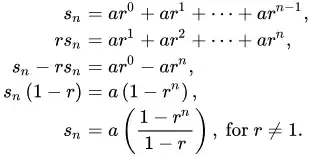

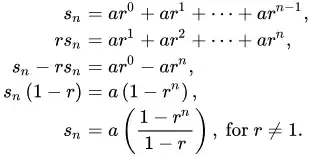

Which is the geometric sum formula. Where a = 1, r = 3, n = 3

So we have the formula $$\frac{1-r^n}{1-r}$$

For b^0 + b^1 + b^2 + ... + b^d, we can plug in the variables: a = 1, r = b, n = d + 1

So we have this amount of vertices:

$$V = \frac{1-b^{d+1}}{1-b} = \frac{-(1-b^{d+1})}{-(1-b)} = \frac{b^{d+1} - 1}{b - 1}$$

So we know, $$O(V) = O(\frac{b^{d+1} - 1}{b - 1})$$

But due to the way Big-O notation works, we know that the formula only matters for significantly large values of b and d. This actually allows us to remove the -1's, as the -1 is likely to be super insignificant if b is a very big number. You can probably use limits with b and d going to infinity to prove this, but I don't want to make this unnecessarily long.

This is just to show a general understanding, of how we get to b^d.

So now we know that $$O(V) = O(\frac{b^{d+1} - 1}{b - 1}) = O(\frac{b^{d+1}}{b}) = O(b^d)$$

$$O(V) = O(b^d)$$

What about E though?

Well we can see from the tree drawing, that for every vertex, there is 1 edge directly above it connected to it. (Except for the root)

So we know that essentially for a tree we have $O(E) = O(V)$, plugging this back into our formula we have $O(V + E) = O(2 \cdot b^d) = O(b^d)$

That was just for a tree though, how do we apply this to any general graph though? Well a tree is always just a subset of a general graph.

And a true breadth-first search never visits the same vertex twice, this is a property that allows us to build a breadth-first search tree. (Similar to a tree built from a depth first search).

So we know that a breadth first search on any general graph will always be $O(V + E) = O(b^d)$

Now onto the bidirectional breadth first search:

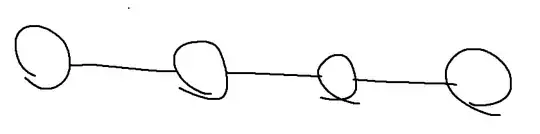

A bidirectional breadth first search starts 1 search from the source, and 1 search from the goal, allowing the two searches to meet halfway.

In essence, if we did a bidirectional breadth first search on a general graph, we'd be drawing 2 trees where their tips/leaves meet each-other.

That is directly $O(2 \cdot b^{d/2}) = O(b^{d/2})$ as each search is only taking half the required steps (d).

But that's now $O(V1 + E1 + V2 + E2)$ (We've split all the edges and vertices into 2 equally large sets).

$$O(V1 + E1) = O(V2 + E2)$$

$$O(V1) = O(E1) = O(V2) = O(E2) = O(b^{d/2})$$

We know their general sizes are equal due to the stuff said earlier about how we have 1 edge for each vertex in the tree, and the fact that the search is cut pretty much perfectly in half.

So we now have $O(V1 + E1 + V2 + E2) = O(4 \cdot b^{d/2}) = O(b^{d/2})$

Now, the weird and funny part, is where we decide to say that $O(V1 + E1 + V2 + E2) = O(V + E)$.

Is this true?

Sort of. Computer Science math related to Big-O notation is sort of this funny part of mathematics, where a lot of it is done somewhat informally. We usually use it to tell ourselves how many steps an algorithm is going to take when we program it. But that's not true here. You shouldn't think of it as the exact amount of steps required for the algorithm to take.

Big-O is only about the growth of the amount of steps required in the worst case for large inputs, and for the types of inputs that give you the worst case.

This is one of those worst cases. If you do a bidirectional search, starting from the left side and right side. Then it becomes more obvious why $O(V1 + E1 + V2 + E2) = O(V + E)$.

But that's generally not what we see for the average case such as a very large graph representing Rubik's cube states. You might use a bidirectional search, starting at your current random state, and starting at the solved state.

This is generally why a lot of people try to draw a difference between amortized (meaning average) worst-case, and actual worst-case. But they'd use Big-O to represent both of them.

The worst-case worst-case is $O(V + E)$. But the amortized worst-case for a lot of specific inputs is more accurately, and not as cleanly represented as $O(V1 + E1 + V2 + E2)$.

But it is cleanly represented as $O(b^{d/2})$

Final note/edit: I hope this general explanation gives somewhat of an understanding on why it is the way it is. It's not meant to be a super formal pure math proof, but it's just meant to say that, the mathematical approach $O(V + E)$ describes the worst case for any type of input we might have. Whereas in real applications, we don't tend to see every type of input out there, so our intuition tells us that $O(V + E)$ doesn't seem right (even though, in a pure mathematical sense it is).