I was solving the following problem, just for reference (441 - Lotto). It basically requires the generation all $k$-combinations of $n$ items

void backtrack(std::vector<int>& a,

int index,

std::vector<bool>& sel,

int selections) {

if (selections == 6) { // k is always 6 for 441 - lotto

//print combination

return;

}

if (index >= a.size()) { return; } // no more elements to choose from

// two choices

// (1) select a[index]

sel[index] = true;

backtrack(a, index+1, sel, selections+1);

// (2) don't select a[index]

sel[index] = false;

backtrack(a, index+1, sel, selections);

}

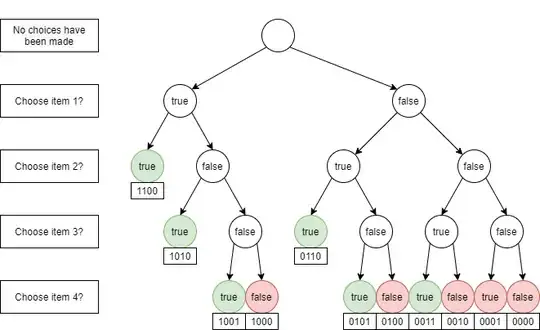

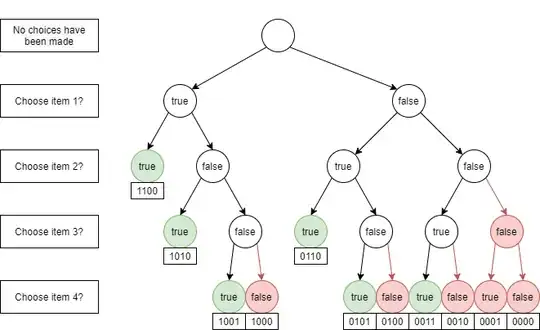

I wanted to analyze my own code. I know at the top level (level = 0), I'm making one call. At the next level (level=1) of recursion, I have two calls to backtrack. At the following level, I have $2^2$ calls. The last level would have $2^n$ subproblems. For each call, we make $O(1)$ work of selecting or not selecting the element. So the total time would be $1+2+2^2+2^3+...+2^n = 2^{n+1} - 1 = O(2^{n})$

I was thinking since we're generating $\binom{n}{k}$ combinations that there might be a better algorithm with a better running time since $\binom{n}{k}=O(n^2)$ or maybe my algorithm is wasteful and there is a better way? or my analysis in fact is not correct? Which one is it?