I understand that if there exist 2 or more left or right derivation trees, then the grammar is ambiguous, but I am unable to understand why it is so bad that everyone wants to get rid of it.

6 Answers

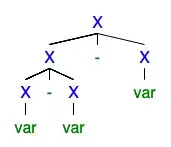

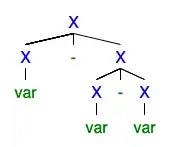

Consider the following grammar for arithmetic expressions: $$ X \to X + X \mid X - X \mid X * X \mid X / X \mid \texttt{var} \mid \texttt{const} $$ Consider the following expression: $$ a - b - c $$ What is its value? Here are two possible parse trees:

According to the one on the left, we should interpret $a-b-c$ as $(a-b)-c$, which is the usual interpretation. According to the one on the right, we should interpret it as $a-(b-c) = a-b+c$, which is probably not what was intended.

When compiling a program, we want the interpretation of the syntax to be unambiguous. The easiest way to enforce this is using an unambiguous grammar. If the grammar is ambiguous, we can provide tie-breaking rules, like operator precedence and associativity. These rules can equivalently be expressed by making the grammar unambiguous in a particular way.

Parse trees generated using syntax tree generator.

- 280,205

- 27

- 317

- 514

In contrast to the other existing answers [1, 2], there is indeed a field of application, where ambiguous grammars are useful. In the field of natural language processing (NLP), when you want to parse natural language (NL) with formal grammars, you've got the problem that NL is inherently ambiguous on different levels [adapted from Koh18, ch. 6.4]:

Syntactic ambuigity:

Peter chased the man in the red sports car

Was Peter or the man in the red sports car?

Semantic ambuigity:

Peter went to the bank

A bank to sit on or a bank to withdraw money from?

Pragmatic ambuigity:

Two men carried two bags

Did they carry the bags together or did each man carry two bags?

Different approaches for NLP deal differently with processing in general and in particular these ambuigities. For example, your pipeline might look as follows:

- Parse NL with ambiguous grammar

- For every resulting AST: run model generation to generate ambiguous semantic meanings and to rule out impossible syntactic ambiguities from step 1

- For every resulting model: save it in your cache.

You do this pipeline for every sentence. The more text, say, from the same book you process, the more you can rule out impossible superfluous models, which survived until step 3, from previous sentences.

As opposed to programming language, we can let go of the requirement that every NL sentence has precise semantics. Instead, we can just bookkeep multiple possible semantic models throughout parsing of larger texts. From while to while, later insights help us to rule out previous ambiguities.

If you want to get your hands dirty with parsers being able to output multiple derivations for ambiguous grammar, have a look at the Grammatical Framework. Also, [Koh18, ch. 5] has an introduction to it showing something similar to my pipeline above. Note though that since [Koh18] are lecture notes, the notes might not be that easy to understand on their own without the lectures.

References

[Koh18]: Michael Kohlhase. "Logic-Based Natural Language Processing. Winter Semester 2018/19. Lecture Notes." URL: https://kwarc.info/teaching/LBS/notes.pdf. URL of course description: https://kwarc.info/courses/lbs/ (in German)

[Koh18, ch. 5]: See chapter 5, "Implementing Fragments: Grammatical and Logical Frameworks", in [Koh18]

[Koh18, ch. 6.4] See chapter 6.4, "The computational Role of Ambiguities", in [Koh18]

- 458

- 2

- 14

Even if there’s a well-defined way to handle ambiguity (ambiguous expressions are syntax errors, for example), these grammars still cause trouble. As soon as you introduce ambiguity into a grammar, a parser can no longer be sure that the first match it gets is definitive. It needs to keep trying all the other ways to parse a statement, to rule out any ambiguity. You’re also not dealing with something simple like a LL(1) language, so you can’t use a simple, small, fast parser. Your grammar has symbols that can be read multiple ways, so you have to be prepared to backtrack a lot.

In some restricted domains, you might be able to get away with proving that all possible ways to parse an expression are equivalent (for example, because they represent an associative operation). (a+b) + c = a + (b+c).

- 1,241

- 9

- 12

Does IF a THEN IF b THEN x ELSE y mean

IF a THEN

IF b THEN

x

ELSE

y

or

IF a THEN

IF b THEN x

ELSE

y

? AKA the dangling else problem.

- 82,470

- 26

- 145

- 239

Take the most vexing parse in C++ for example:

bar foo(foobar());

Is this a function declaration foo of type bar(foobar()) (the parameter is a function pointer returning a foobar), or a variable declaration foo of type int and initialized with a default initialized foobar?

This is differentiated in compilers by assuming the first unless the expression inside the parameter list cannot be interpreted as a type.

when you get such an ambiguous expression the compiler has 2 options

assume that the expression is a particular derivation and add some disambiguator to the grammar to allow the other derivation to be expressed.

error out and require disambiguation either way

The first can fall out naturally, the second requires that the compiler programmer knows about the ambiguity.

If this ambiguity stays undetected then it is possible that 2 different compilers default to different derivations for that ambiguous expression. Leading to code being non-portable for non-obvious reasons. Which leads people to assume it's a bug in one of the compilers while it's actually a fault in the language specification.

- 4,696

- 1

- 18

- 15

I think the question contains an assumption that's only borderline correct at best.

In real life it's pretty common to simply live with ambiguous grammars, as long as they aren't (so to speak) too ambiguous.

For example, if you look around at grammars compiled with yacc (or similar, such as bison or byacc) you'll find that quite a few produce warnings about "N shift/reduct conflicts" when you compile them. When yacc encounters a shift/reduce conflict, that signals an ambiguity in the grammar.

A shift/reduce conflict, however, is usually a fairly minor problem. The parser generator will resolve the conflict in favor of the "shift" rather than the reduce. The grammar is perfectly fine if that's what you want (and it does seem to work out perfectly well in practice).

A shift/reduce conflict typically arises in a case on this general order (using caps for non-terminals and lower-case for terminals):

A -> B | c

B -> a | c

When we encounter a c, there's an ambiguity: should we parse the c directly as an A, or should we parse it as a B, which in turn is an A? In a case like this, yacc and such will choose the simpler/shorter route, and parse the c directly as an A, rather than going the c -> B -> A route. This can be wrong, but if so, it probably means you have a really simple error in your grammar, and you shouldn't allow the c option as a possibility for A at all.

Now, by contrast, we could have something more like this:

A -> B | C

B -> a | c

C -> b | c

Now when we encounter a c we have conflict between whether to treat the c as a B or a C. There's a lot less chance that an automatic conflict resolution strategy is going to choose what we really want. Neither of these is a "shift"--both are "reductions", so this is a "reduce/reduce conflict" (which those accustomed to yacc and such generally recognize as a much bigger problem than a shift/reduce conflict).

So, although I'm not sure I'd go quite so far as to say that anybody really welcomes ambiguity in their grammar, in at least some cases it's minor enough that nobody really cares a whole lot about it. In the abstract they might like the idea of removing all ambiguity--but not enough to always actually do it. For example, a small, simple grammar that contains a minor ambiguity can be preferable to a larger, more complex grammar that eliminates the ambiguity (especially when you get into the practical realm of actually generating a parser from the grammar, and finding that the unambiguous grammar produces a parser that won't run on your target machine).

- 731

- 4

- 10