$\def\dbl{\mathrm{dbl}}$Okay, let's give the missing step between mikeazo's and poncho's answers.

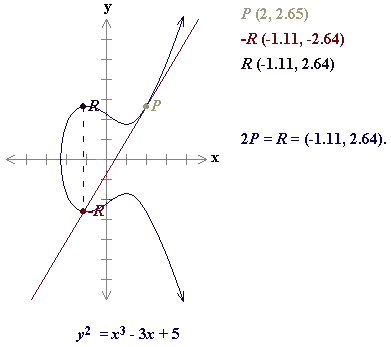

I assume you've read mikeazo's answer to know how to add and double points.

Now, how do we get a scalar multiple of a point?

A simple algorithm is called "double-and-add", as it just does this.

In a simple example, we have $5 = 4 + 1 = 2·2 + 1$, and thus $5·P = (2·2+1)·P = 2·2·P + P$. So we calculate $P → \dbl(P) = 2·P → \dbl(\dbl(P)) = 4·P → 4·P + P=5·P$.

For your example of $200$, we have $200 = 128 + 64 + 8 = 2^7 +2^6+2^3$, and thus $200·P = 2^7·P + 2^6·P + 2^3·P$, which can be calculated as $\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(P))))))) + \dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(\dbl(P)))))) + \dbl(\dbl(\dbl(P)))$. (Of course, you would calculate the common sub-terms only once.)

Alternatively, we can use the distributive law to write it this way: $200·P = 2·2·(2·2·2·(2·P + P) + P)$.

(Note that we used the binary form of the scalar factor here to decide when to add and when not to add.)

Here are two general forms of this algorithm to calculate $d·P$, when $d$ has the binary form $d_kd_{k-1}\dots d_1d_0$ (assuming d_k = 1):

Starting from the small-endian bits:

Q := 0

R := P

for i = 0 .. k:

if(d_i = 1)

Q = add(Q, R)

R = double(R)

return Q

Starting from the big-endian bits:

Q := 0

for i = k ... 0:

Q := double(Q)

if(d_i = 1)

Q := add(Q, P)

return Q

Note that this is actually the same algorithm you are using for modular (or other) exponentiation, just with the operations square and multiply instead (and then usually named square-and-multiply).

Also, this trivial implementation is quite vulnerable to a power analysis attack, if implemented on a smart card, as doubling and adding doesn't use quite the same amount of power, and the adding is only done when a bit in the (usually secret) exponent is set. There are measures against this, and also a bit more efficient point multiplication algorithms – any book about elliptic curves should mention some of them.