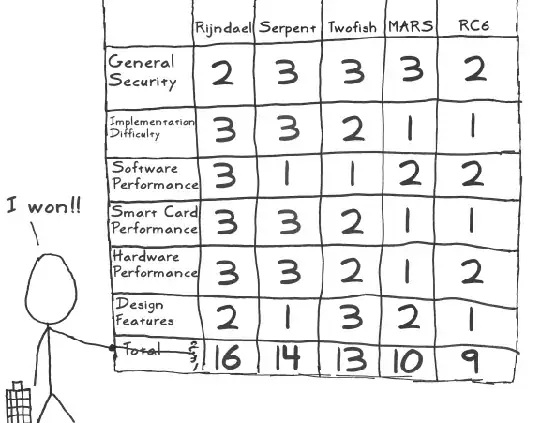

I was just reading the Stick Figure Guide to AES and came across an interesting table explaining how the winner was chosen:

Unfortunately the NIST site is down so I can't gain further information about the approval process so I was hoping someone here would know in more detail.

- Who or what decided on the numbers in this table which ranks each algorithm? I.e. can the exact analysis process be described?

- Who created that process? People in NIST or an equally divided group of government, industry and public cryptographers?

- What is included in "Design Features"? I.e. What were those features that were important?

- "Performance" analysis could have been done with benchmarks but "Implementation Difficulty" sounds subjective. How was that quantified?

- Could the numbers in that table been tweaked to skew the results in favor of a particular algorithm?

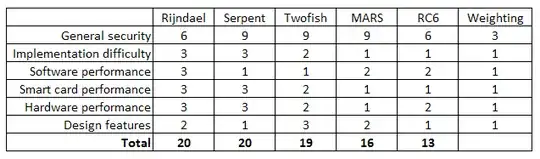

Those questions aside and assuming the magic numbers above were arrived at a fair and equitable process without bias or hidden agendas, it seems to me this table or ranking system is still missing a "weighting" criteria. All categories seem to be weighted with the same importance. That is "Smart Card Performance" is equally important as "General Security". That seems incorrect. I would argue that security is of the utmost importance so that should have a higher weighting relative to the other criteria which would be secondary concerns. A good quote would be:

Security at the expense of usability, comes at the expense of security.

I wondered what would happen if I applied a high weighting factor to security and left the other points as they are. For example:

Now Serpent is first equal with Rijndael with Twofish coming in a close second. Interesting.

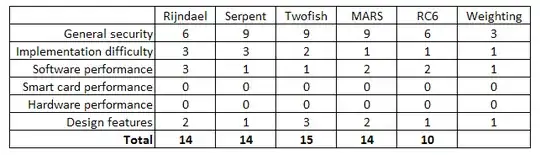

What about if I am developing a software product, I don't care about about hardware performance or smart card performance so I can rule those two out completely in my decision. The table might look like this:

Now Twofish is the winner and Rijndael is second equal with Serpent and MARS. MARS might even be more attractive with its variable key size up to 448 bits.

My overall point is that Rijndael, Serpent, Twofish and MARS all appear to be within the same ballpark quality range as far as block ciphers go and this rating criteria. There might be a more accurate mathematical way to apply a weighting factor. If I was revamping the security on a project and concerned about NSA involvement in weakening encryption standards then I could re-weight some of the criteria and priorities to suit my project's specific goals. I might decide on a different algorithm from Rijndael. Back in 2000 Rijndael might have suited the US government's purposes and planned surveillance agendas but not my project's. I would compare it to selecting an algorithm just like TrueCrypt gives you the option of choosing between 3 different algorithms. Would that be a reasonable call?