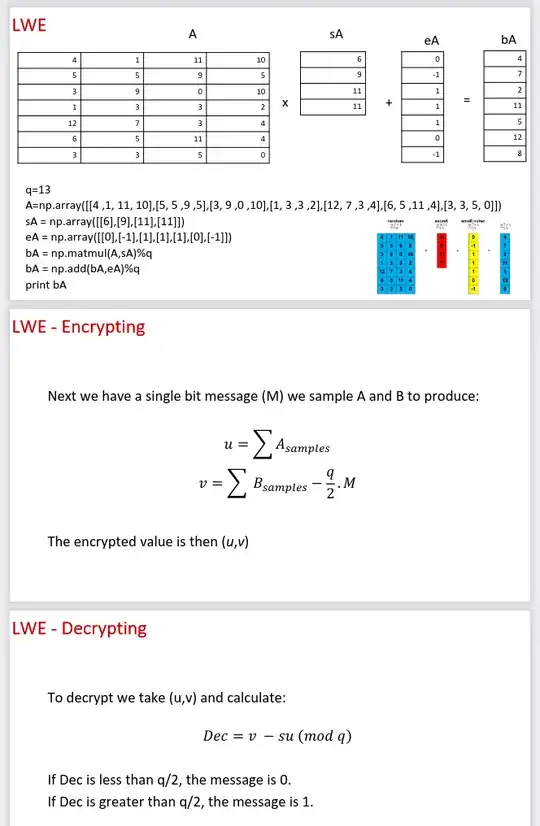

Someone told me that when decrypting we get $qM/2 + r e$. If we can

bound $r e$ by $q/4$ then we can retrieve $M$ by checking if this is closer

to 0 or $q/2$. May I ask how bounding $r e$ by $q/4$ helps ?

In this case, $M$ is either $0$ or $1$ and what we actually receive on decrypting is a value $d=qM/2+re\mod q$. Suppose for example that $q=10,000$, then

- $qM/2$ will be either 0 (corresponding to $M=0$) or

- It will be 5000 (corresponding to $M=1$).

If we can be sure that $|re|\le 2499$ then

- in the case $M=1$ our decryption can only lie in $[2501,7499]$ and

- in the case $M=0$ our can only lie in the ranges $[0,2499]$ and $[7501,9999]$.

These ranges do not overlap and so recovery of $M$ is unambiguous.

On page 33 of the similar document, what is the purpose of the

assumption on $\alpha$? and how to derive the expressions for this

assumption and its corresponding probability?

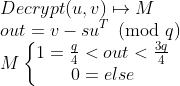

In these slides, $\alpha$ is chosen to be the standard deviation of the discretised Gaussian from which the coefficients of $\mathbf e$ are sampled. Likewise, coefficients of $\mathbf r$ are taken to be either 0 or 1 based on independent coin-flips. This means that the value $\mathbf r\cdot\mathbf e$ is the sum of approximately $m/2$ discrete Gaussian samples, each with standard deviation $\alpha q$ and so we expect this value to be distributed roughly Gaussian with standard deviation $\sqrt{m/2}\alpha q$. By the choice $\alpha=o(1/\sqrt m\log n)$, the standard deviation of $\mathbf r\cdot\mathbf e$ will be $o(q/\sqrt{\log n})$ and so the chance of observing a value of absolute value greater than $q/4$ will be bounded by the chance of observing a Gaussian outside of $\sqrt{\log n}/o(1)$-standard deviations. Standard tail estimates for the Gaussian distribution then apply to give the bound $n^{-1/o(1)}$ on the probability of such an event.

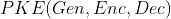

![\

Gen() \mapsto (PublicKey, SecretKey) \

PublicKey: [A,B] \

A: \mathbb{Z}{q}^{m\times n}\

n: \text{Independent variable} \

m: \text{Amount of ecuations} \

q: \text{prime number} \

B: A\times SecretKey + e \pmod{q}\

SecretKey: \mathbb{Z}{n}^{q} \

e: \mathbb{Z}^{m}](../../images/a2f9da066d7b792372144b4692a7f3cf.webp)