According to Fowler, Mariantoni, Martinis, and Cleland, 2012, Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation (PRL link, page 29), braiding transformations are doing the same thing that CNOT and its adjacent are doing to 2Q gates:

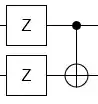

$$\hat{CNOT}\:^\dagger\big(\hat I\otimes\hat X\big)\hat{CNOT}\:^=\hat I\otimes \hat X,\\ \hat{CNOT}\:^\dagger\big(\hat X\otimes\hat I\big)\hat{CNOT}\:^=\hat X\otimes \hat X,\\ \hat{CNOT}\:^\dagger\big(\hat I\otimes\hat Z\big)\hat{CNOT}\:^=\hat Z\otimes \hat Z,\text{and}\\ \hat{CNOT}\:^\dagger\big(\hat Z\otimes\hat I\big)\hat{CNOT}\:^=\hat Z\otimes \hat I.$$

which is exactly what a braiding transformation is doing.

And they say that therefore, braiding is analogous to CNOT.

But I say no! - it is analogous to $$\hat{CNOT}\:^\dagger\big(2Qubit Operator)\hat{CNOT}\:^.$$ which is 2 CNOTs, and not one CNOT!

Can someone settle this for me please?

Thank you!