I'm a graphical artist who is completely out of my depth on this site.

However, I'm dabbling in WebGL (3D software for internet browsers) and trying to animate a bouncing ball.

Apparently we can use trigonometry to create nice smooth curves.

Unfortunately, I just cannot see why.

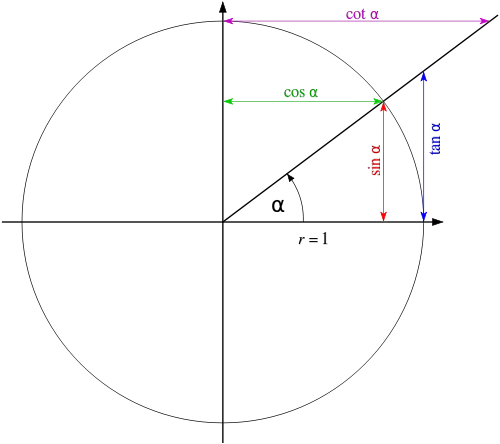

I can accept this diagram:

However, running some calculations just do not make sense to me:

Let's set $\alpha$ to 45 (around where it appears to be in the diagram) and find the cosine value, thus giving us the green line. $$\cos(45) = 0.5$$

Fair enough. $\cos(\alpha)$ / the green line is $0.5$ units.

But now this is where it all falls apart. I would have thought if we set $\alpha$ to $90$, $\cos$ would become $0$. Do you see why I think this? Look at the digram, isn't that reasonable to think? Similarly, $\cos(0)$ I would have said should equal $1$ (twice that of $\cos(45)$ )

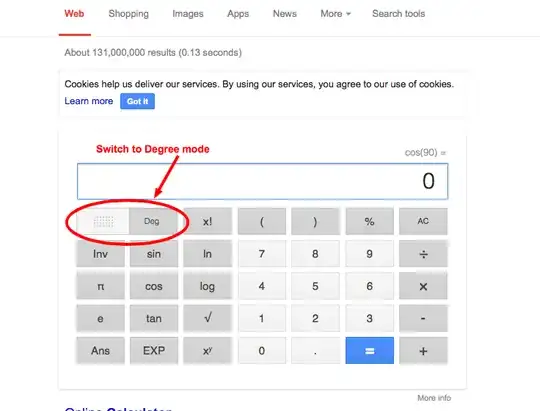

While $\cos(0)$ does equal $1$, this does not check out: $$ cos(90) = -0.4$$

Just do not get that $0.4$? Could someone explain? That just makes no sense to me. None.

I'm using the google calculator and I would stress I have not touched maths for about $6$ years (ever since I left school!) so please lots of examples and words to explain!

40°.45°is half of a right angle and it doesn't seem to be half. – Qwerty May 13 '14 at 09:23diameterof2, right? Judging from the fact thatcos(0Pi)=1andcos(1Pi)=-1? – Starkers May 13 '14 at 12:21