We can quickly compute a representation of a prime $ \,p\equiv 1\pmod{\!4}\,$ as a sum of two squares by using the Euclidean GCD algorithm in $ \mathbb Z[i]\,$ (and a $\!\bmod p\,$ square root algorithm).

Theorem $\ $ Let $ \ \, c = \sqrt{-1}\pmod{\!p}\, $ and $\,\gcd(p,\,i-c) = a+b\,i\ $.$\ $ Then $ \ p = a^2 + b^2\,$.

Proof $\ $ We shall show: $\ [\![1]\!]\, $ Representing $ \, p\,$ as a sum of squares is equivalent to finding a proper splitting $ \, p = \alpha\beta\ $ in $ \, \mathbb Z[i].\,$ $ [\![2]\!]\ $ Since $\,\Bbb Z[i]\,$ has a Euclidean algorithm, a proper splitting of $ \, p\,$ can be computed by GCD with a suitable splitting of some multiple of $ \, p.\,$ $ [\![3]\!]\ $ A suitable splitting of some multiple of $ \, p\,$ arises by factoring $\, x^2+1\pmod{\!p},\,$ i.e. by computing $\,c = \sqrt{-1}\pmod{\!p}.$

$ [\![1]\!]\ $ If $ \,\alpha\mid p\ $ properly, conjugating $\:\!\Rightarrow \alpha'\mid p\ $ properly. Multiplying $\,\Rightarrow\,\alpha\alpha'\mid p^2$ properly in $\,\Bbb Z,\,$ where $\,p\,$ is the only proper factor $>0$ of $\,p^2,\,$ so $ \, p = \alpha\alpha' = (a\!+\!b\,i)(a\!-\!b\,i) = a^2\! + b^2.$

$ [\![2]\!]\, \ p\gamma = \alpha\beta,\,$ $p\nmid\alpha, \beta\,$ $\Rightarrow\, \gcd(\alpha,p)\mid p\,$ properly. Else $\,\gcd(\alpha,p) = p\,$ or $1.\,$ If the gcd is $\,p\,$ then $ \, p\mid\alpha\,$ contra hypothesis. Hence $ \ \gcd(\alpha,p)=1\, $ so by Euclid's Lemma $\, \alpha\mid p\,\gamma\, \Rightarrow\, \alpha\mid\gamma\,$ thus $\, \gamma/\alpha = \beta/p\, \Rightarrow\, p\mid \beta,\,$ again contra hypothesis. $ $ [Note: $ $ generally, in rings, GCDs are unique only up to unit multiples. Here the units are $ \ i^n = \pm 1,\,\pm i\,$].

$ [\![3]\!]\,\ x^2 + 1 = (x\!-\!c)(x\!+\!c) + p\, f(x)\ $ in $\,\Bbb Z[x]\, \overset{\large x\,=\,i}\Longrightarrow -p\, f(i) = (i\!-\!c)(i\!+\!c)\, $ in $\,\Bbb Z[i].\,$ By $[\![2]\!]$ this splitting is suitable to split $ \,p\,$ since $ \,p\nmid i\pm c\,$ in $\,\Bbb Z[i].$

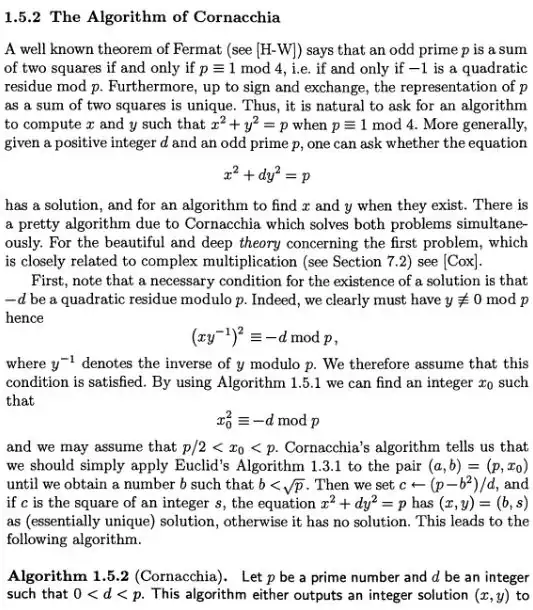

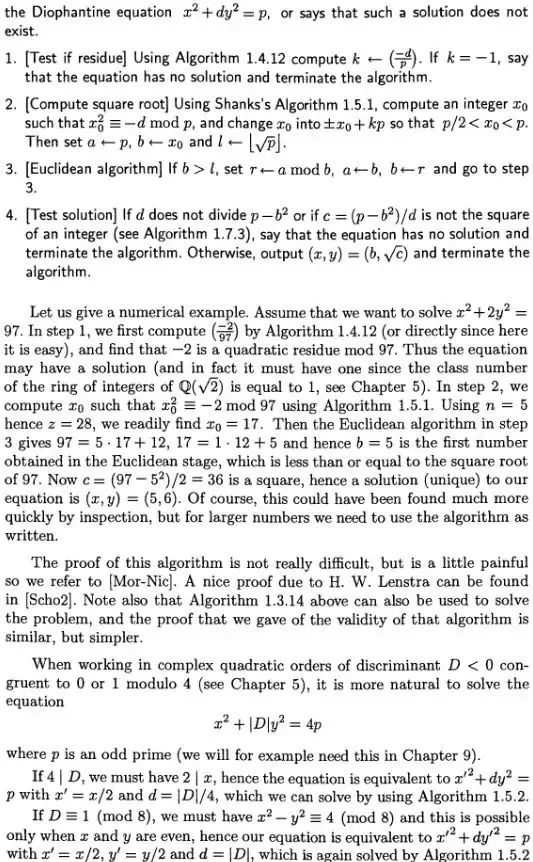

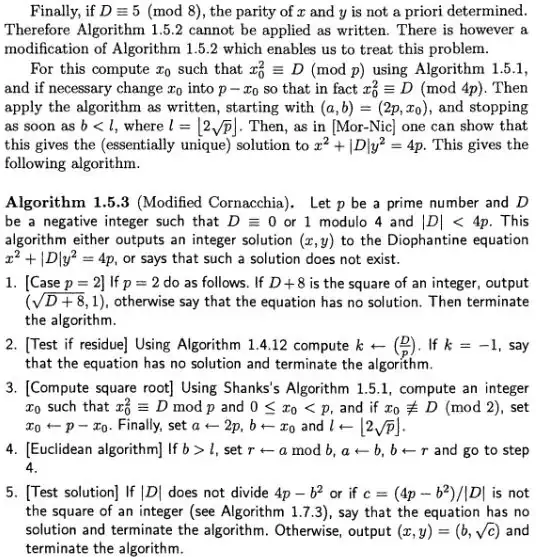

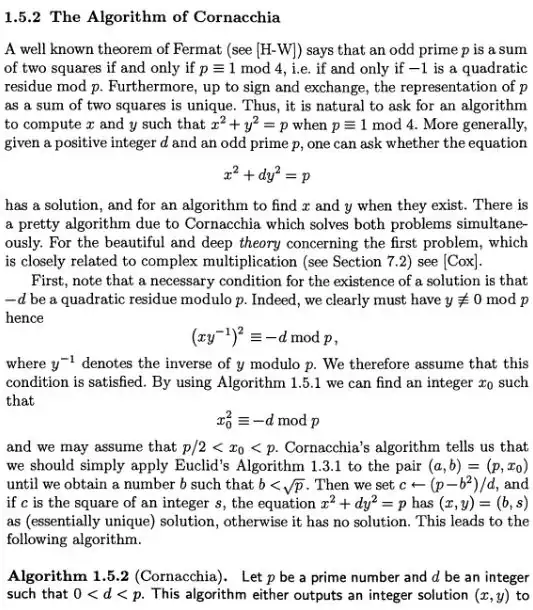

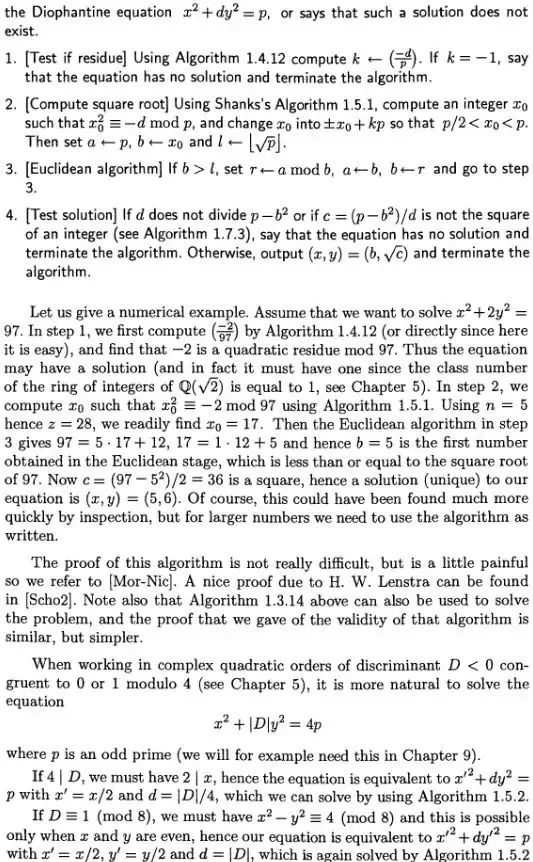

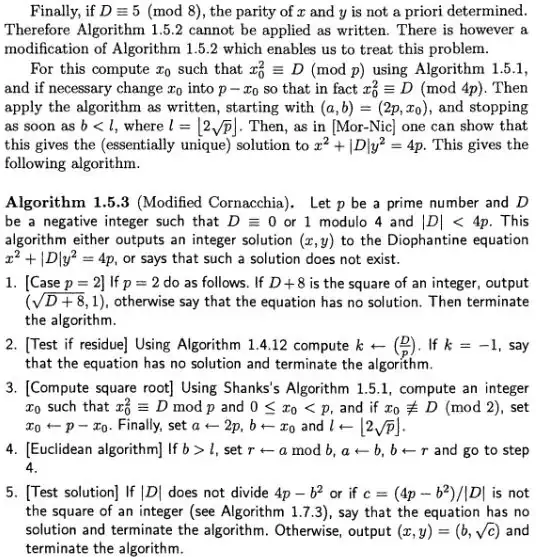

Remark $ $ There are many variations on the Euclidean algorithm in the Gaussian integers $\,\Bbb Z[i],\,$ e.g. employing continued fractions, binary quadratic forms, etc. Also, there are also at least a few algorithms for computing sqrts $\!\!\pmod{\!p},\,$ e.g. by factoring polynomials, by elliptic curves (Schoof), Tonelli, Shanks. For much further information see Henri Cohen's book A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory. Below is an excerpt on Cornacchia's algorithm.

http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1972771/is-this-the-general-solution-of-finding-the-two-original-squares-that-add-up-to

– user25406 Oct 18 '16 at 19:37