A challenge problem asked to show that if rectangle $R$ with axis-parallel sides is partitioned into finitely many subrectangles $R_1,R_2,\ldots,R_n$ (also with axis-parallel sides), such that each $R_i$ has at least one integer side length, then $R$ must also have at least one integer side length. The only proof I've seen, although simple, is quite unintuitive. Namely you look at the integral $$ \int_R e^{2 \pi i (x+y)} dx dy $$ and note that the integral is $0$ if and only if $R$ has an integer side length, and then note that by assumption the integral is $0$ over all the $R_i$, hence summing the integral over all $R_i$ gives that the integral is also $0$ over $R$. Can someone give a more direct/intuitive argument that doesn't use voodoo like a complex-valued integral?

-

I don't even understand the complex integral proof. Could you expand a bit? – Jack M Oct 02 '13 at 16:14

-

@JackM from Euler's identity we know that $e^{i x}$ repeats itself with a period of $2\pi$ and $\int_0^{1} e^{2\pi i x} dx = 0$ thus if the length of the $x$ domain for $R$ is an integer this integral is zero. Similarly for $y$, thus if either one of them is an integer length the product is zero. – Dan Oct 02 '13 at 16:19

-

There is an article with 14 proves of the stated theorem. Maybe you will find an intuitive one among them. – LRDPRDX Aug 07 '18 at 01:44

-

Please, pay attention to eighth proof. – LRDPRDX Aug 07 '18 at 02:26

5 Answers

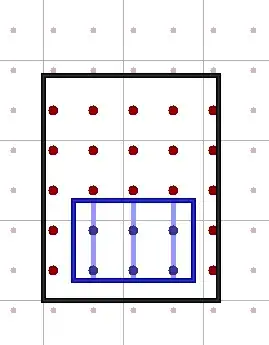

Make the plane into a giant checkerboard grid with squares of size $\tfrac{1}{2}\times\tfrac{1}{2}$. In this problem we consider only rectangles with sides parallel to the axes. It is (intuitively) clear that such a rectangle with a side of integer length covers equal amounts of black and white area.

Let $R$ be a rectangle of size $a\times b$ partitioned into finitely many subrectangles, each having a side of integer length. Note that $R$ then covers equal parts black and white, because each of the smaller rectangles does. Without loss of generality we may assume that the lower left corner of $R$ is at the origin.

Divide $R$ into two rectangles of sizes $\lfloor a\rfloor\times b$ and $(a-\lfloor a\rfloor)\times b$, with the first rectangle having its lower left corner at the origin. The first covers equal amounts of black and white. The second can again be subdivided into two rectangles of sizes $$(a-\lfloor a\rfloor)\times\lfloor b\rfloor\qquad\text{ and }\qquad(a-\lfloor a\rfloor)\times(b-\lfloor b\rfloor),$$ with the former having one side adjacent to an axis. This rectangle again cover equal parts black and white. The latter rectangle must then also cover equal parts black and white.

Note that this smaller rectangle is positioned in the lower left corner of a unit square, covered by precisely two black and two white squares. For it to cover equal parts black and white, one of its sides must have integer length. But for $a-\lfloor a\rfloor$ or $b-\lfloor b\rfloor$ to be an integer, it must be zero. We conclude that either $a$ or $b$ is an integer, and hence that $R$ has a side of integer length.

- 67,306

- 8

- 82

- 171

First let's assume an additional constraint: that we may only partition rectangles by splitting them in two, recursively.

Note that when we split the largest rectangle into two, we may only achieve the integer constraint on the two sub-rectangles if at least one of the sides of the parent rectangle has an integer side also.

Now, let's relax the additional splitting in two constraint by noting that any configuration of rectangles can be achieved by recursively splitting and then merging adjacent rectangles - noting that the original large rectangle still has an integer side.

This sounds right in my head - please pick holes in it :)

- 104

-

1I voted up, but now I'm not sure. Splitting can destroy the property (P) "every rectangle has an integer side" and merging can create this property. So how do we know that property (P) was false at the beginning (i.e. false of the big rectangle) and was created during the merging stage? – Trevor Wilson Oct 02 '13 at 16:41

-

I believe the first part, so if a rectangle is a recursive union of two rectangles per parent rectangle then the result holds, but I'm not yet sure how the construction and proof verification works for the second "relaxed" part. I'll think a bit and if I figure it out, I'll upvote and accept. Meanwhile if you can fill in more details for the second part, that would be great. – user2566092 Oct 02 '13 at 16:46

-

My thinking was that: you may only split when preserving property P with subrectangles. And, given this rule, merging always results in property P also (since merging compatible rectangle with property P has to also result in P). – Luke Oct 02 '13 at 16:50

-

1This is not true actually. Consider a rectangle $R$ with another rectangle $R_1$ positioned exactly in the centre of $R$. Then from each of vertex of $R_1$, extend the edge of $R_1$ until reaches the edge or $R$. Do this for each vertex of $R_1$, clockwise w.l.o.g. Or just imagine one of those expanding camera lenses but square. This is a valid tiling in which no tiles can be combined into another tile. If this wasn't the case, then merging tiles would indeed work. – Ruochan Liu Jul 02 '22 at 19:48

I believe I have completed the proof, unless someone can find a gap. Per the original argument I posted, we know the result holds when all side lengths of subrectangles are rational of the form $q/p$ for fixed prime $p$. So assume we have a rectangle without integer sides, such that each subrectangle has an integer side. Let $r_x = |x - \lbrace{x \rbrace}|$ and $r_y = |y - \lbrace{y \rbrace}|$ be the distances of the overall side lengths of the original rectangle to the nearest integer. Choose prime $p$ so that $r_x,r_y$ are both greater than $2/p$. We can approximate the rectangle and subrectangles by replacing each vertex with the closest rational vertex coordinates of the form $q/p$. Then each approximated subrectangle has an integer side, and so the approximated overall rectangle must also have an integer side. But this means the original rectangle must have either $r_x$ or $r_y$ less than or equal to $2/p$, a contradiction.

- 26,450

If $R$ doesn't have an integer-sized side, you can draw a grid on the rectangle, with horizontal and vertical lines placed everyy $\frac 1 2$ units, such that there is an odd number of grid points inside the rectangle.

Since every small rectangle contains an even number of grid points, you have a contradiction.

Here is an example within a rectangle of size $2+? * 2+?$

- 51,119

I can prove it assuming that all side lengths of subrectangles are rationals of the form $q/p$ where $p$ is a fixed prime. In that case, if we scale the rectangle and subrectangles by a factor of $p$ then we get that all side lengths are integers, and all subrectangles have a side length divisible by $p$, and we want to show that the overall rectangle also has a side length divisible by $p$. But this is trivial: every subrectangle has area divisible by $p$, so the total area of the overall rectangle is also divisible by $p$, and hence at least one side of the total rectangle must have length divisible by $p$.

- 26,450

-

"Every subrectangle has area divisible by p" - no, if a rectangle has width and height of length 1/p and $\sqrt{2}$, then this rectangle will not have an area divisible by p. – mercury0114 Feb 25 '18 at 21:17

-

And the problem does not assume that both sides of a rectangle are rational. – mercury0114 Feb 25 '18 at 21:18