Your idea of the rope spanned over a circle is the right way of atacking such problems. The method is called Euler-Lagrangian equations of motion with undetermined parameters simulating the boundary of a free particle taking the shortest path between two points; avoiding an area with such a high potential (a high mountain with steep flanks), that would be slowing down the velocity, such that any path circumventing the area is cheaper wrt to kinetic energy and shorter wrt to travel time.

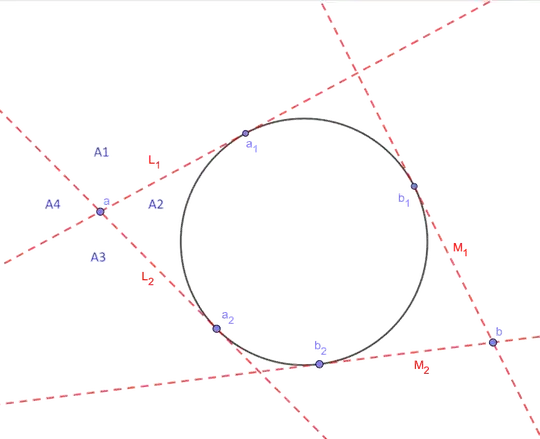

Lagranges method of undetermined free parameters is using an arbitrary high potential energy inside the forbidden area resulting in a very hard, potentially infinite, elastic repulsion forces acting orthogonal to the tangent of the boundary, such that the boundary causes a momentum reflection if the path touches the boundary.

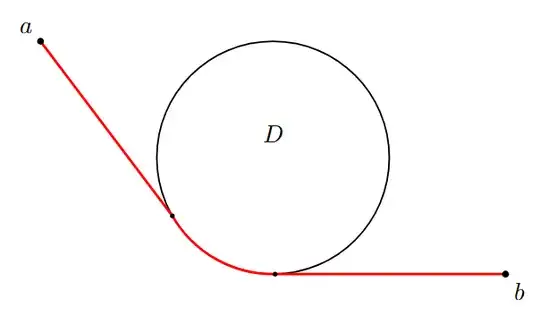

Without much mathematical ado it easy to show that the shortest path is a series of straight lines and pieces of the boundary, that between first and last touch of the boundary forms a convex hull og its inner segment between the two touching points.

For a segment of the circle the convex hull is the segment itself.

If there are defects or inward curved parts of the segment, they are bridged by shortest straight thangents.

In a way this is old roman art of road construction, were the number of stones and brigdes on the on hand and the travel tíme and coast on the other hand were the variation principles for the engineers to find the optimal route.

As a mathematical profund description the method needs so much of calculus of variation and differential geometry, that it fills about half of any textbook of theoretical mechanics.