The existence of intermediate logics between intuitionistic logic and classical logic is well known (for example, adding $(A \to B) \lor (B \to A)$ as an "axiom of linearity" to Heyting's logic defines Gödel-Dummett logic, a logic stronger than intuitionistic logic but weaker than classical logic). But is there an argument to exclude the possibility of an intermediate logic between minimal logic and intuitionistic logic or, on the contrary, an argument to assert that such an intermediate system is possible?

Reminder: in intuitionisitic logic, we have $$\lnot \lnot A \nvdash A $$ contrarily to classical logic, and in minimal logic, we have $$\bot \nvdash C$$ contrarily to intuitionistic logic.

Here is what should be a clue to answer my question. In intuitionistic logic, the assumption of the classical theorem called "Dummett's formula", that is,

$$(A \to B) \lor (B \to A)$$

does not entail the law of elimination of double negation: \begin{equation*} \tag{1} (A \to B) \lor (B \to A) \nvdash_{i} \lnot \lnot A \to A \end{equation*}

We can therefore add $(A \to B) \lor (B \to A)$ to the system of intuitionistic logic to obtain an intermediate system.

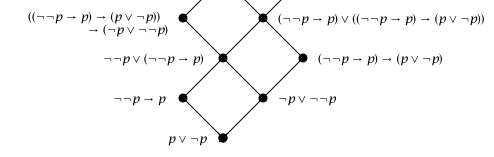

Is there a formula that is provable in intuitionistic logic, but not in minimal logic, and that is such that its assumption in minimal logic does not entail the explosion rule? If there is such a formula, adding this formula to minimal logic would provide an intermediate logic. On the contrary, if it is provable that such a formula does not exist, it must be admitted that there is no intermediate logic between minimal logic and intuitionistic logic.

Contrarily to the first reply made to this question, my intuition is "No, there is no intermediate logic between minimal and intuitionistic logic". Here is a sketch of argument: the proof of any formula F that is provable only thanks to the explosion rule contains a contradiction of two literals, say $\lnot A$ and $A$, to get an atomic formula B via the explosion rule. The assumption of F in minimal logic must therefore entail this instance of explosion rule. For example, this sequent: \begin{equation*}\tag{2} ( (A \lor B) \land \lnot A) \to B \vdash (\lnot A \land A) \to B \end{equation*} is provable in minimal logic, by contrast with (1) where the assumption of the Dummett formula does not entail the provability of an instance of the rule of Double Negation Elimination. That is why I suspect there is no intermediate logic between minimal logic and intuitionistic logic, at least not like in the well-known case of intermediate logics between intuitionistic logic and classical logic.