A field must have a unit element. Without loss of generality we can assume that element to be: $e_1 = (1, 0)$.

From this we get $e_1^2 = 1$, $e_1e_2 = e_2$.

The only remaining unknown is ${e_2}^2$.

We will denote $e_1 = 1$ and $e_2=i$ for convenience.

Let $i^2 = x + iy$ for some $x$ and $y$.

Our multiplication is:

$$(a+ib)(c+id) = ac +i(ad+bc)+i^2(bd)=\\

=(ac + x\;bd) +i(ad + bc + y\; bd) $$

We will examine how our choice of $x,y$ for $i^2 = x + i\; y$ affects the structure of our algebra. We have:

$$(a+ib)^2 = (a^2 + b^2 x) + i(2 a b + b^2 y)$$

Solving $(a+ib)^2 = -1$ gives us:

$$a+ib =\pm \frac{y-i2}{\sqrt{-(4x+y^2)}}$$

Therefore, when (and only when) $i^2 = x+iy$ satisfies $4x+y^2 < 0$, we can set: $a+ib = \frac{y-i2}{\sqrt{-(4x+y^2)}}$ as our new imaginary unit (squaring to -1), and our algebra is isomorphic to the complex numbers. This still leaves $2$ more cases to be examined:

When $i^2 = x+iy$ satisfies $4x+y^2 > 0$, we can solve $(a+ib)^2 = 1$ giving us:

$$a+bi=\pm 1 \;\;\text{or}$$

$$a+ib =\pm \frac{y-i2}{\sqrt{4x+y^2}}$$

Setting $a+ib =\frac{y-i2}{\sqrt{4x+y^2}}$ as our imaginary unit shows this algebra isomorphic to the split-complex numbers .

When $i^2 = x+iy$ satisfies $4x+y^2 = 0$, we can solve $(a+ib)^2 = 0$ giving us:

$$a+ib = (\frac{y}{2}-i)*c$$ for any choice of constant factor $c$. Setting $a+ib = y-i 2$ as our new imaginary unit shows the algebra to be isomorphic to the dual numbers.

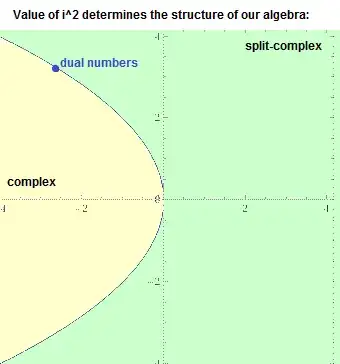

In summary, if we set $i^2 = x+iy$, the sign of $4x+y^2$ determines the structure of our algebra:

$4x+y^2 < 0$ makes it isomorphic to the complex numbers, which have $i^2=-1$

$4x+y^2 > 0$ makes it isomorphic to the split-complex numbers, which have $i^2 = 1$

$4x+y^2 = 0$ makes it isomorphic to the dual numbers, which have $i^2 = 0$

A field, in addition to having a unit element must have no divisors of zero.

The split-complex and dual numbers do not satisfy these conditions (eg. $(1+i)(1-i)=0$ for split-complex and $i^2 = 0$ for duals), therefore are not fields.

Therefore, every field structure of $\mathbb{R}^2$ is isomorphic to $\mathbb{C}$.

Dropping the field requirements (existence of a unit element and a lack of zero-divisors) allows for far richer algebraic structures, which have been referenced in the other answer to this question.