Summary

After some numerical investigation and heuristic arguments, I come to the following conclusions:

- The optimal value achievable is $n/2 - \Theta(\sqrt{n})$.

- Numerically, it seems pretty close to $n/2 - \sqrt{n}$.

- Theoretically, I have most of an argument that one can't do better than $n/2 - \Omega(\sqrt{n})$.

- Theoretically, I have sketched an argument that one can achieve value $n/2 - O(\sqrt{n})$.

- A near-optimal policy is the square-root gap policy: when there are $k$ balls in the urn, accept a ball of the leading color if and only if the current gap is less than $\sqrt{k}$.

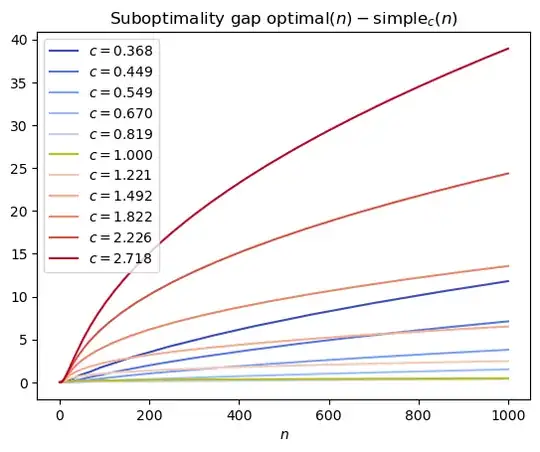

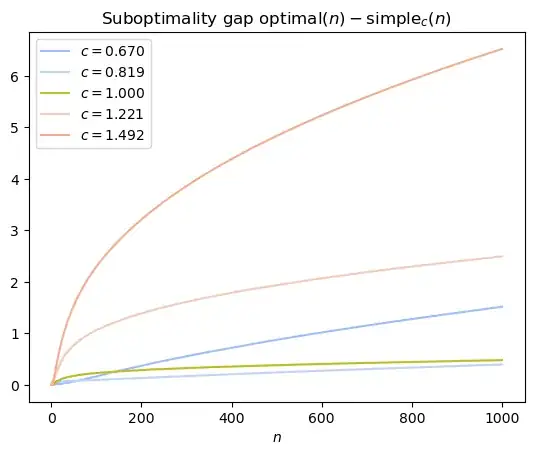

- Numerically, I tried gap limits of the form $c \sqrt{k}$ for several constants $c$, and $c = 1$ appears to be the best for large $n$, with a suboptimality gap that remains much less than $1$.

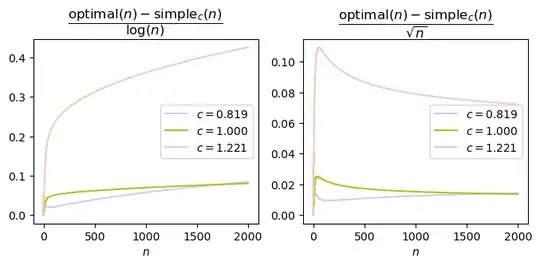

I conjecture that the square-root gap policy achieves expected value that is $o(\sqrt{n})$ less than the optimal value. I wouldn't be surprised if it were constant, because as of $n = 2000$, the suboptimality gap is still only $0.611$.

All code is included in an appendix.

Numerical investigations

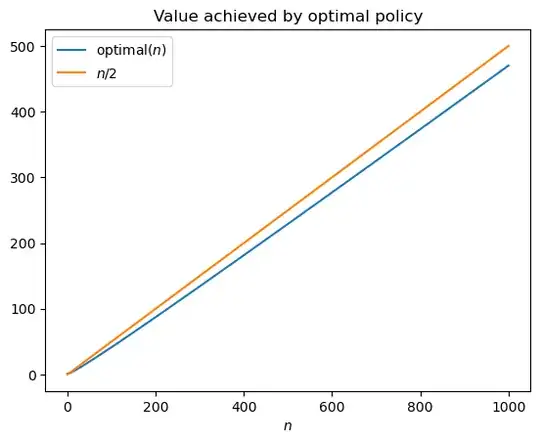

Value of the optimal policy

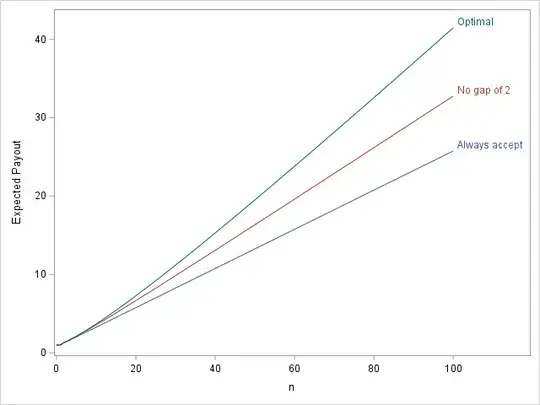

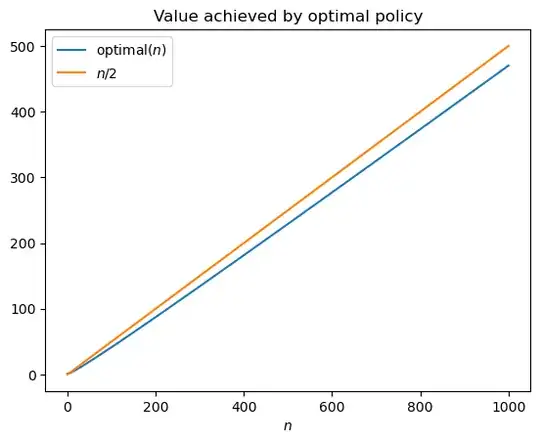

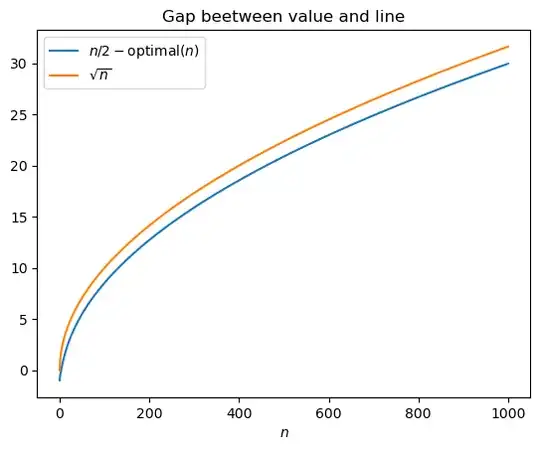

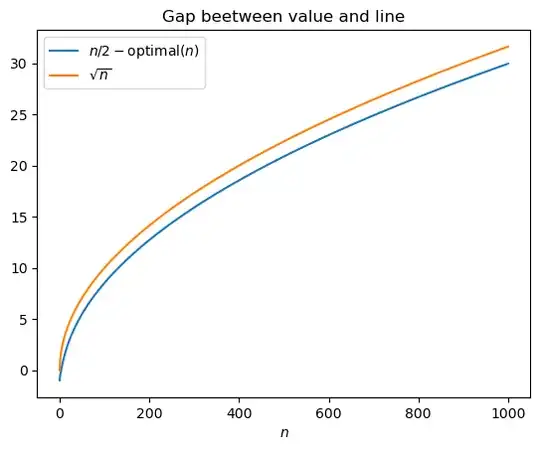

Using dynamic programming, we can compute the optimal value of the optimal policy (along the lines of RobPratt's answer). The following two plots shows that $\text{optimal}(n)$, the value of the optimal policy, is (a) pretty close to $n/2$, and (b) the gap between them is slightly less than $\sqrt{n}$.

This is somewhat surprising: $n/2$ is the best we could possibly hope for, and we can achieve something pretty close to that. The fact that the value gap is $\sqrt{n}$ suggests that at the end, the gap between the colors is probably something like $\Theta(\sqrt{n})$ on average. This inspires a simple heuristic policy: always keep at most a square-root sized gap.

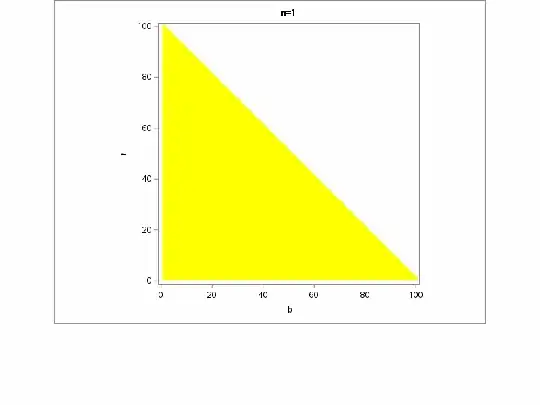

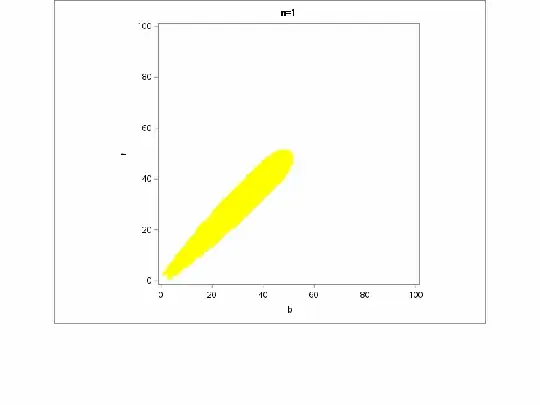

Simple heuristic: $c$-square-root gap policy

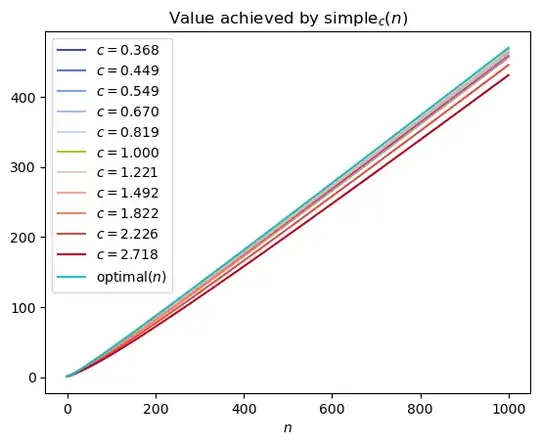

Let $\text{simple}_c(n)$ be the value of the $c$-square-root gap policy that operates as follows. Suppose there are $r$ red, $b$ blue, and $k = r + b$ total balls, and WLOG say $r > b$. The policy always accepts blue, but it only accepts red if $r - b < c \sqrt{k}$.

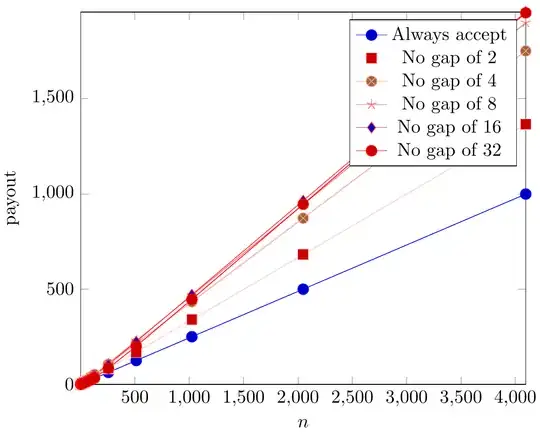

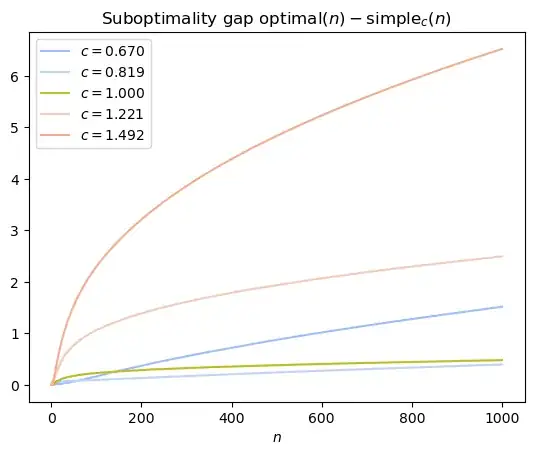

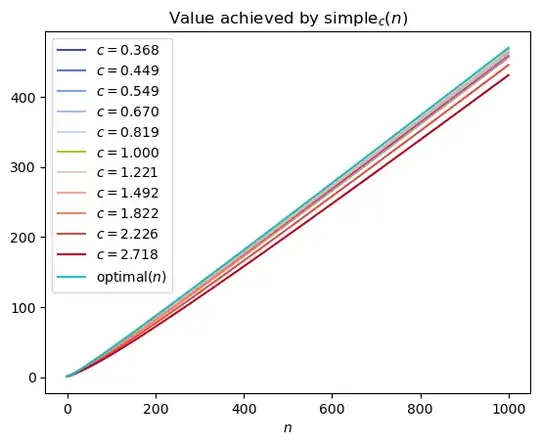

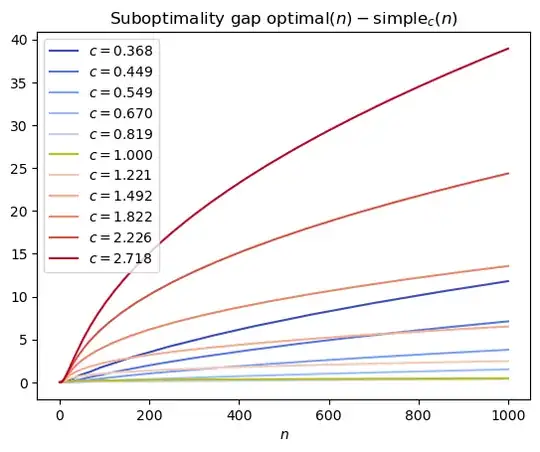

The following plots show that for a range of values of $c$, the $c$-square-root gap policy is pretty close to optimal. The specific case of $c = 1$ is highlighted yellow-green.

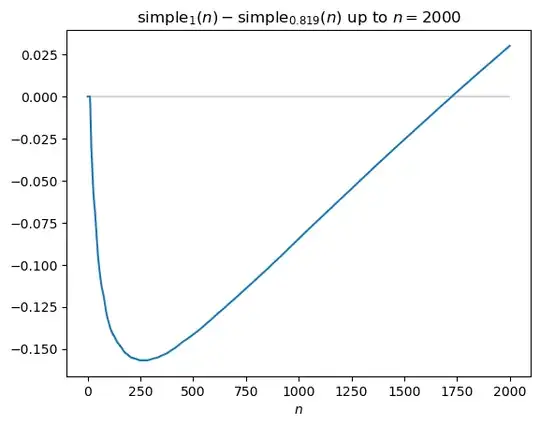

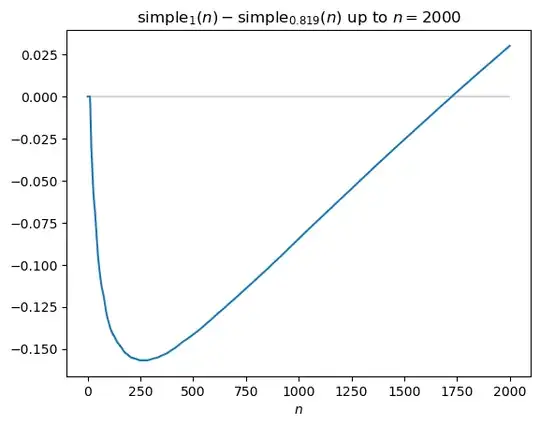

Zooming in on the best performers, it initially looks like $c < 1$ might outperform $c = 1$, but looking at larger values of $n$, it seems like $c = 1$ is the right choice asymptotically.

[update] Suboptimality gap of the $1$-square-root gap policy

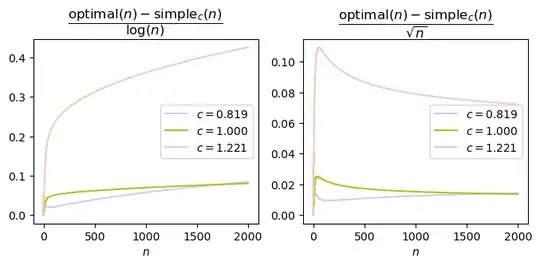

I initially thought the suboptimality gap of the $1$-square-root policy might be constant. However, after making the plot below, I'm no longer fully convinced: it's conceivable that the gap is growing logarithmically, or even slightly faster. I do suspect it's still $o(\sqrt{n})$.

Heuristic arguments

There are two things we can argue theoretically:

- The optimal value is at most $n/2 - \Omega(\sqrt{n})$.

- One can achieve a value at least $n/2 - O(\sqrt{n})$.

I'm not going to write full proofs, though I believe turning these arguments into full proofs is possible.

Upper bound

Here's why the optimal value is at most $n/2 - \Omega(\sqrt{n})$. Imagine that every time step, we proposed adding red or blue each with probability $1/2$, instead of probabilities according to the current state. This increases the chance of proposing the trailing color, which should only help the optimal value. (This conclusion is the main thing that needs to be formalized.)

But now that we have equal-probability proposal colors, it never hurts to accept a ball, so we always accept. So the process becomes one driven by an unbiased random walk. Specifically, letting $S_n = \sum_{i = 1}^n B_i$ for $B_i \sim \operatorname{Uniform}\{-1, 1\}$ i.i.d., we have, by a central limit theorem approximation,

$$

\text{optimal}(n) \leq \frac{n}{2} - \mathbb{E}[|S_n|] \approx \frac{n}{2} - \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi} n}.

$$

Lower bound

Here's a policy that I think achieves value at least $n/2 - O(\sqrt{n})$. It's a variant of the $c$-square-root gap policy, but with a change to make the dynamics mimic an unbiased random walk. Specifically, at every step:

- If the $c$-square-root gap policy would reject a leading-color ball in this state, do the same.

- If $c$-square-root gap policy would accept a leading-color ball in this state, then if a leading-color ball is drawn, reject it with some probability. Choose the probability such that the overall probability of accepting a leading-color ball equals that of accepting a trailing-color ball.

This means the number of balls evolves as a random walk with pauses, plus extra rejections from the gap hitting the $c \sqrt{k}$ barrier, where $k$ is the number of balls in the current state.

We now sketch why the number of rejections is at most $O(\sqrt{n})$. Because we keep a $c \sqrt{k}$ gap, this means the eventual value achieved is at least $n/2 - c \sqrt{k} - O(\sqrt{n}) = n/2 - O(\sqrt{n})$.

We first count the random rejections, those from list item 1 above. Because we're always maintaining a gap of at most $c \sqrt{k}$, the expected number of random rejections is

$$

\mathbb{E}[\text{number of random rejections}] \leq \sum_{k = 2}^{n + 1} O\biggl(\frac{1}{\sqrt{k}}\biggr) \leq O(\sqrt{n}).

$$

We should be able to use a concentration inequality to refine this into a high-probability statement. This means we're effectively running the $c$-square-root gap policy, but with equal-probability ball color proposals, for $n - O(\sqrt{n})$ steps.

To conclude, we need to argue that we only reject due to hitting the barrier $O(\sqrt{n})$ times, assuming equal-probability ball color proposals. I believe this is true but difficult to show. The rough idea is that an unbiased random walk will take, in expectation, $\ell - 1$ time to go from $1$ to either $0$ or $\ell$. This should mean that if we hit the barrier with $k$ balls in the urn, we'll reject some constant number of times to get away from the barrier, then take $\Omega(\sqrt{k})$ time in expectation until we next hit a barrier. Of course, the number of balls is increasing, but that should only further delay the time until the next barrier hit.

The above analysis can likely be adapted to the $c$-square-root gap policy without the random rejections, because the $\ell - 1$ hitting time should still approximately hold with slight bias in the walk. A policy that just uses random rejections with no barrier might also work, but one would need to show it doesn't get stuck in a state early on where it rejects a large number of leading-color balls.

Appendix: code

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def dp_step_opt(v):

"""One step of dynamic programming, optimal policy

Parameters

----------

v : array of shape `(n, n)`

Value function as a function of the number of reds and blues

for some fixed number of time steps from the end.

Returns

-------

out : array of shape `(n - 1, n - 1)`

Value function for one more time step from the end.

"""

v = np.asarray(v)

i = np.arange(v.shape[0] - 1)[:, np.newaxis]

j = np.arange(v.shape[1] - 1)[np.newaxis, :]

p = (i + 1) / (i + j + 2)

return (

# v[i, j] == v[:-1, :-1]

# v[i + 1, j] == v[1:, :-1]

# v[i, j + 1] == v[:-1, 1:]

p * np.maximum(v[:-1, :-1], v[1:, :-1])

+ (1 - p) * np.maximum(v[:-1, :-1], v[:-1, 1:])

)

def dp_step_simple(c, v=None):

"""One step of dynamic programming, simple square-root heuristic policy

Alternative usage: instead of `dp_step_simple(c, v)`,

can call as `dp_step_simple(c)(v)`.

Parameters

----------

c : float

Constant for use in gap bound: when there are `k` balls in the urn,

reject if the current gap is greater than `c * sqrt(k)`.

v : array of shape `(n, n)`

Value function as a function of the number of reds and blues

for some fixed number of time steps from the end.

Returns

-------

out : array of shape `(n - 1, n - 1)`

Value function for one more time step from the end.

"""

if v is None:

return lambda v: dp_step_simple(c, v)

v = np.asarray(v)

i = np.arange(v.shape[0] - 1)[:, np.newaxis]

j = np.arange(v.shape[1] - 1)[np.newaxis, :]

p = (i + 1) / (i + j + 2)

d_max = c * np.sqrt(i + j + 2)

return (

# v[i, j] == v[:-1, :-1]

# v[i + 1, j] == v[1:, :-1]

# v[i, j + 1] == v[:-1, 1:]

p * np.where(i - j >= d_max, v[:-1, :-1], v[1:, :-1])

+ (1 - p) * np.where(j - i >= d_max, v[:-1, :-1], v[:-1, 1:])

)

def dp(n, dp_step=dp_step_opt):

"""Dynamic programming for entire process

Parameters

----------

n : int

Number of steps.

dp_step : callable, default=dp_step_opt

One-step dynamic programming function, which encodes the policy used.

Returns

-------

out : list of arrays, `i`th of shape `(n + 1 - i, n + 1 - i)`

Value functions for each number of time steps left.

Overall value of the `i`-step game is `out[i][0, 0]`.

"""

i = np.arange(n + 1)[:, np.newaxis]

j = np.arange(n + 1)[np.newaxis, :]

vs = [1.0 + np.minimum(i, j)]

for _ in range(n):

vs.append(dp_step(vs[-1]))

return vs

Value of optimal policy

dp_1000 = dp(1000)

v_opt = np.array([v[0, 0] for v in dp_1000])

ns = np.arange(len(v_opt))

Figure 1

plt.plot(v_opt, label=r"$\text{optimal}(n)$")

plt.plot(ns / 2, label="$n/2$")

plt.title("Value achieved by optimal policy")

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Figure 2

plt.plot(ns / 2 - v_opt, label=r"$n/2 - \text{optimal}(n)$")

plt.plot(np.sqrt(ns), label=r"$\sqrt{n}$")

plt.title("Gap beetween value and line")

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Value of simple policy

cvs_simple = [

(c, np.array([v[0, 0] for v in dp(1000, dp_step=dp_step_simple(c))]))

for c in np.exp(np.linspace(-1, 1, 11))

]

def color(c):

if c == 1:

return 'C8'

else:

return plt.get_cmap('coolwarm')(0.5 + 0.5 * np.log(c))

Figure 3

for c, v_simple in cvs_simple:

plt.plot(v_simple, label=fr"$c = {c:.3f}$", color=color(c))

plt.plot(v_opt, label=r"$\text{optimal}(n)$", color='C9')

plt.title(r"$\text{Value achieved by }\text{simple}_c(n)$")

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Figure 4

for c, v_simple in cvs_simple:

plt.plot(v_opt - v_simple, label=fr"$c = {c:.3f}$", color=color(c))

plt.title(

r"$\text{Suboptimality gap }\text{optimal}(n) - \text{simple}_c(n)$"

)

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Value of simple policy, longer horizon

cvs_simple_2000 = [

(c, np.array([v[0, 0] for v in dp(2000, dp_step=dp_step_simple(c))]))

for c in np.exp(np.linspace(-1, 1, 11))[4:7]

]

Figure 6

plt.hlines(0, 2000, 0, color='lightgray')

plt.plot(cvs_simple_2000[1][1] - cvs_simple_2000[0][1])

plt.title(

r"$\text{simple}1(n) - \text{simple}{0.819}(n)$ up to $n = 2000$"

)

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.show()

Estimating the suboptimality gap

dp_2000 = dp(2000)

v_opt_2000 = np.array([v[0, 0] for v in dp_2000])

ns_2000 = np.arange(len(v_opt_2000))

print(v_opt_2000[-1] - cvs_simple_2000[1][1][-1])

-> np.float64(0.6111886241664024)

Figure 7

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

for c, v_simple in cvs_simple_2000:

plt.plot(

(v_opt_2000 - v_simple)[2:] / np.log(ns_2000[2:]),

label=fr"$c = {c:.3f}$", color=color(c),

)

plt.title(r"$\dfrac{\text{optimal}(n) - \text{simple}_c(n)}{\log(n)}$")

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

for c, v_simple in cvs_simple_2000:

plt.plot(

(v_opt_2000 - v_simple)[2:] / ns_2000[2:]**(1/2),

label=fr"$c = {c:.3f}$", color=color(c),

)

plt.title(r"$\dfrac{\text{optimal}(n) - \text{simple}_c(n)}{\sqrt{n}}$")

plt.xlabel("$n$")

plt.legend()

plt.show()