Compiling and (over?-)expanding my comments to @RobinSparrow's answer ...

Loomis' maxim "Trigonometry is because the Pythagorean Theorem is" is succinct and catchy ... and wrong. :)

(Well, it's correct from a certain point of view. We'll get to that.)

I prefer: "Trigonometry is because similarity is."

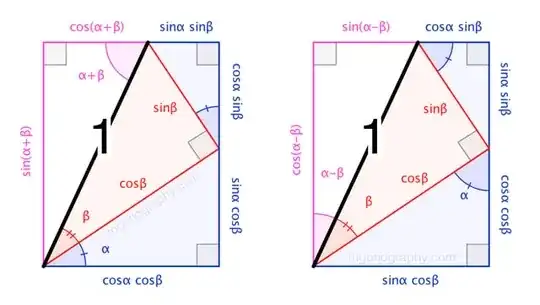

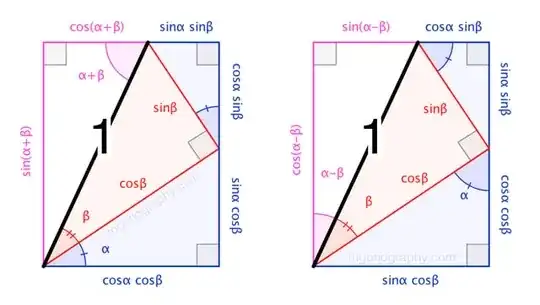

After all, the identity $\sin x/\cos x=\tan x$ is nothing more than an algebraic consequence of the SOHCAHTOA definitions. The same is true for any result derived via mere ratio-chasing through a diagram ... for instance, the Angle-Sum and -Difference identities (via my trigonography site):

$$\begin{align}

\sin(\alpha\pm\beta) &= \,\sin\alpha\cos\beta\pm\cos\alpha\sin\beta \tag1\\

\cos(\alpha\pm\beta) &= \cos\alpha\cos\beta\mp\,\sin\alpha\sin\beta \tag2

\end{align}$$

These are certainly "fundamental formulae", yet they are not "based upon the truth of the Pythagorean Theorem", despite Loomis' blanket declaration that "all [of them] are".

Perhaps to Loomis, ratio-chasing amounts to elementary geometry —a kind of pre-trigonometry— while trigonometry-proper only comes into its own upon the introduction of the Unit Circle, which brings with it an inherent dependence upon Pythagoras, which in turn justifies his maxim. That's a not-unreasonable stance, but the qualification needs to be clearly articulated to avoid confusion among those (myself and many? most? almost-all? others) with a more-inclusive view —especially non-experts (eg, journalists) who may lack an awareness of the distinction between, say, Right-Triangle trig and Unit Circle trig— or else we'll keep getting questions like this one. ;)

Regarding the Johnson-Jackson proof, and others whose trigonometric components are of the ratio-chasing variety, the upshot is this:

The oft-overlooked nuance in Loomis' oft-cited rejection of "trigonometric" proofs of Pythagoras is that Loomis' rejection does not apply to ratio-chasing arguments, simply because Loomis' particular conception of "trigonometric" does not apply to ratio-chasing arguments.

So, people need to stop dismissing any Pythagorean proof that happens to feature a sine or cosine as automatically circular "because Elisha Loomis said so". He didn't.

As I've commented elsewhere, Calcea Johnson and Ne’Kiya Jackson deserve applause for their cleverness. However, inflated claims that these precocious high-schoolers somehow "accomplished the impossible" only do them a disservice.

Granted, as I repeat myself from this answer, caution is advised when considering such things, as it's all-to-easy to inadvertently invoke a Pythagorean identity. Indeed, in the 1940 edition of The Pythagorean Proposition (PDF link via ed.gov) (p 244), Loomis follows-up the passage highlighted in @RobinSparrow's answer by calling-out such an error in Jan Versluys' previous compilation of proofs:

Therefore the so-styled Trigonometric Proof, given by J. Versluys, in his Book, Zes en Negentig Bewijzen, 1914 (a collection of 96 proofs), p. 94, proof 95, is not a proof since it employs the formula $\sin^2A+\cos^2A=1$.

Versluys #95 (shown in a screenshot in this answer on History of Science and Math SE) amounts to substituting $\alpha+\beta=90^\circ$ into $(1)$ ...

$$\sin^2\alpha+\cos^2\alpha=\sin\alpha\cos\beta+\cos\alpha\sin\beta=\sin(\alpha+\beta)=\sin90^\circ=1$$

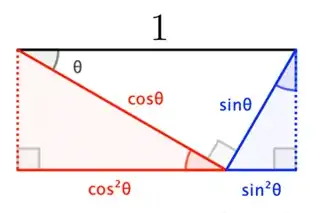

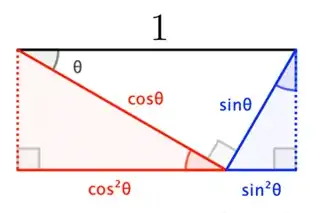

... which seems all well and good, except that that final, innocuous-looking equality is subtly dependent upon the Pythagorean Theorem (say, by way of the Unit Circle). Observe that if we grant ourselves a $1$ from the get-go, we can avoid this pitfall and arrive a what amounts to the standard high-school proof by ratio-chasing:

$$1 = \cos^2\theta+\sin^2\theta$$

(Note that this serves as the $\alpha+\beta=90^\circ$ limiting case of the Angle-Sum trigonograph above.)

Versluys may be suggesting something (ahem) similar by writing:

If one arranges this proof in such a way that one avoids the trigonometric relations, by including the proof of the first formula, then one arrives at the proof by means of proportionality of the sides of triangles having equal angles.

I'll stop typing now. :)