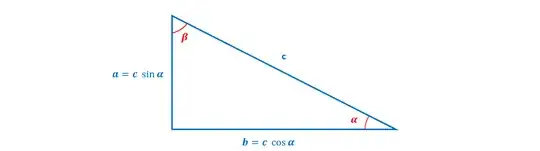

Let $\alpha$ be the angle opposite to side $a$, and $\beta$ be the angle opposite to side $b$, and without loss of generality, assume that $0 < \alpha \leq \beta < 90^\circ$.

We now have:

$$\begin{align} \cos(\beta) &= \cos(\alpha − (\alpha − \beta)) \\ &= \cos(\alpha) \cos(\alpha − \beta) + \sin(\alpha) \sin(\alpha − \beta) \\ &= \cos(\alpha)(\cos(\alpha) \cos(\beta) + \sin(\alpha) \sin(\beta)) + \sin(\alpha)(\sin(\alpha) \cos(\beta) − \cos(\alpha) \sin(\beta)) \\ &= (\cos^2(\alpha) + \sin^2(\alpha)) \cos(\beta), \end{align}$$

from which it follows that $\cos^2(\alpha) + \sin^2(\alpha) = 1$, since $\cos(\beta)$ is the ratio between one leg and the hypotenuse of a right triangle, and as such is never zero. The theorem now follows from the definitions of sine and cosine and scaling.

I am not sure if I am understanding the proof correctly; I have trouble getting what the "scaling" means and why it is necessary.