The standard formula for a Riemann sum of an integral is as follows: $$\int_a^b f(x) dx = \lim_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i) \Delta x$$ where $\Delta x = \frac{b-a}{n}$ and $x_i = a+i\Delta x$.

Since in the limit this sum is infinite, my question thus is

Can it be possible for the sum to be conditionally convergent?

If so, what is the function $f(x)$ that satisfies this? My intuition tells me that no, but real analysis is full of obscure and weird counterexamples.

Everything that follows below is my attempt. I approach at constructing this was to somehow replicate the alternating harmonic series: $$\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{i+1}}{i}$$ which converges conditionally. My early attempts all depended on the value of $n$, which the function $f(x)$ should not depend on. I managed to construct something like the sum though:

Let the interval on which we will work on be $[0,1]$ (not sure if it is open or closed). Thus $\Delta x = \frac{1}{n}$. Now, define $r(x) = \lfloor\frac{1}{x}\rfloor$, and $f(x) = (-1)^{r(x)} r(x)$. The idea for the $r(x)$ term is to somehow "cancel" the effects of the small $\Delta x$ term as $x\to 0$.

If I try and directly substitute the values into the Riemann sum I get something like this: $$\int_0^1 f(x) dx = \lim_{n\to\infty} \sum_{i=1}^n (-1)^{\lfloor\frac{n}{i}\rfloor} \lfloor\frac{n}{i}\rfloor \frac{1}{n}$$ and I really don't know what to do with this. Also notice that $f(0)$ is undefined so I am not sure if this sum is a well-defined value at all.

I also tried doing this: Consider

$$\int_\epsilon^1 f(x) dx$$

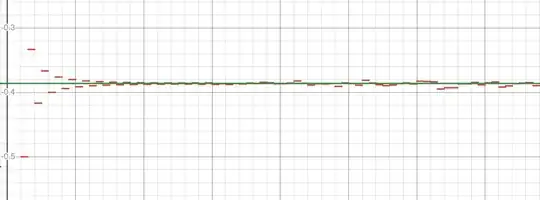

for $\epsilon> 0$. I let $\epsilon = \frac{1}{N}$ for some $N \in \mathbb{N}$. The graph that I get for the value of this integral for different values of $N$ looks as follows:

which seems to converge like the alternating series but breaks for numerical

reasons past some point. In any case, does the corresponding Riemann sum converge conditionally?

which seems to converge like the alternating series but breaks for numerical

reasons past some point. In any case, does the corresponding Riemann sum converge conditionally?

I also tried an alternative definition for $f(x)$: $f_2(x) = (-1)^{r(x)}$. This behaves very similarly, and may be an easier approach to this. This time Desmos is able to directly compute the integral from 0 to 1 (denoted by the green line).

EDIT: I figured out the value of the integral of $f(x)$:

$$\int_{0}^{1} f(x) dx = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \left(\frac{1}{k} - \frac{1}{k+1}\right)\cdot (-1)^k k = \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^k}{k+1} = \ln(2) - 1$$ However, this sum converges conditionally. I got the formula by having an infinite sum of integrals: $$\int_{0}^{1} f(x) dx = \int_{1/2}^{1} f(x) dx + \int_{1/2}^{1/3} f(x) dx + \cdots + \int_{1/k}^{1/(k+1)} + \cdots$$ Would this mean that the linearity of the integral operator can break when we have infinitely many terms, because the sum is conditionally convergent and thus by rearranging the terms (the integrals) it can have a different value?