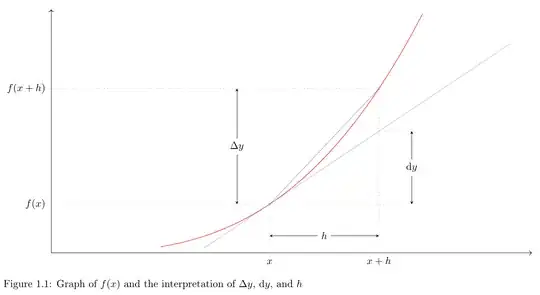

Let $f(x)$ be an arbitrary function, as shown in the figure below (Figure 1.1).

When $x$ increases by $h$, the change in $y$ is straightforward: $$ \Delta y = f(x+h) - f(x). $$

The average rate of change with respect to $h$ (where $h \neq 0$) is given by: $$ \frac{\Delta y}{h} = \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}. $$

So far, this makes sense to me.

Now, I'm struggling with two things:

First:

I understand that Leibniz's notation, $\frac{dy}{dx}$, is just that — a notation. What it represents is the limit: $$ \lim\limits_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}. $$ But what about $dy$? Is $dy$ also "just" a notation, or does it have a different meaning? My interpretation is that: $$ dy = \left\{\lim\limits_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \right\} \cdot dx. $$ Is this correct?

Second:

Using Leibniz's notation, I could write: $$ dy = \frac{dy}{dx} \cdot dx. $$ However, this form contains two identical $dx$ symbols. One is in the denominator of $\frac{dy}{dx}$ (which is part of Leibniz's notation and doesn’t represent anything specific), and the other $dx$ represents the step in $x$. In this context, $dx = h$. This confuses me because both are written the same, but seem to mean different things. Can someone explain how to interpret these two $dx$ symbols correctly?