Consider the problem from Introduction to Algorithms by Cormen et. al below:

Suppose we use a hash function h to hash n distinct keys into an array T of length m . Assuming simple uniform hashing, what is the expected number of collisions? More precisely, what is the expected cardinality of {{k,l}:k≠l and h(k)=h(l)} ?

This question has been asked in multiple forms - and answered - multiple times (1, 2, 3, 4) and the correct result is $\frac{n(n−1)}{2m}$.

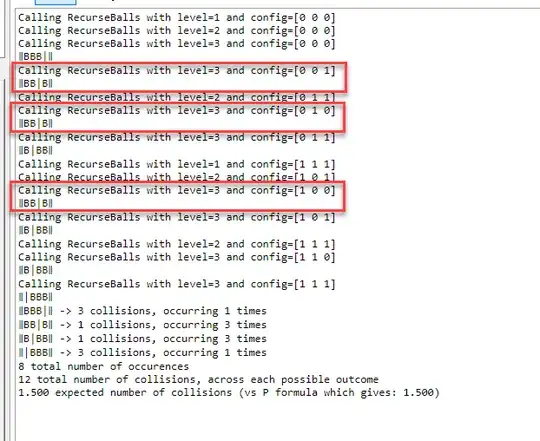

What I'm after is to actually "see" how that final number comes to be. For this I'm running the problem with low values of m and n. I'm also thinking of balls and bins to picture the whole thing, as at least for me it makes it less abstract. To get all the possible combinations of the balls landing into bins I use the idea from this video where we can simplify the problem by considering all possible permutations of m letters B (B for "ball") and a divider sign (separator between bins, so there will be m-1 such signs).

Finally I count the number of collisions - make sure to take into account the actual definition of "collision" for this problem (e.g. one new ball dropping into a bin with 3 existing balls will result in 3 collisions, then a new ball placed in the same bin will generate 3 more collisions, etc). I then divide the number of overall collisions found when generating all possible permutations by the number of permutations themselves, and get the average number of collisions.

For 3 balls and 2 bins I get (whereby the correct formula gives $\frac{6}{4}=1.5$)

∥BBB|∥ -> 3 collisions

∥BB|B∥ -> 1 collisions

∥B|BB∥ -> 1 collisions

∥|BBB∥ -> 3 collisions

4 combinations found

2 average collisions (8 overall collisions / 4 combinations)

For 5 balls and 3 bins we get (whereby the correct formula gives $\frac{20}{6}=3.333$)

∥BBBBB||∥ -> 10 collisions

∥BBBB|B|∥ -> 6 collisions

∥BBBB||B∥ -> 6 collisions

∥BBB|BB|∥ -> 6 collisions

∥BBB|B|B∥ -> 3 collisions

∥BBB||BB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥BB|BBB|∥ -> 6 collisions

∥BB|BB|B∥ -> 3 collisions

∥BB|B|BB∥ -> 3 collisions

∥BB||BBB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥B|BBBB|∥ -> 6 collisions

∥B|BBB|B∥ -> 3 collisions

∥B|BB|BB∥ -> 3 collisions

∥B|B|BBB∥ -> 3 collisions

∥B||BBBB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥|BBBBB|∥ -> 10 collisions

∥|BBBB|B∥ -> 6 collisions

∥|BBB|BB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥|BB|BBB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥|B|BBBB∥ -> 6 collisions

∥||BBBBB∥ -> 10 collisions

21 combinations found

5.714286 average collisions (120 overall collisions / 21 combinations)

Simulations for higher values of m and n show the same pattern: the number of collisions I compute is always higher than the correct answer.

My question is simply what am I doing wrong?