I learned the following convention.

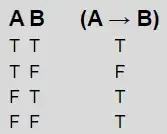

Convention 1:

Let $P,Q$ be statements.

If $P$ is a false statement, then $P\implies Q$ is true.

Convention 1 works perfectly anytime.

Why?

For example,

Proposition 1:

Suppose $n\in\mathbb{N}$.

Then for any $x\in n$, $x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Proof:

If $n=0$, then by Convention 1, for any $x\in 0,x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Suppose $n\in\mathbb{N}$ and for any $x\in n$, $x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Let $x$ be any element of $n\cup\{n\}$.

If $x\in n$, then $x\in\mathbb{N}$ by induction hypothesis.

If $x=n$, then $x=n\in\mathbb{N}$.So, by induction, if $n\in\mathbb{N}$, then for any $x\in n$, $x\in\mathbb{N}$.

I think the above proof is the standard proof but I would like to prove Proposition 1 as follows and tend to prove Propostion 1 as follows:

Proof:

If $n=0$, then by Convention 1, for any $x\in 0,x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Suppose $n\in\mathbb{N}$ and for any $x\in n$, $x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Let $x$ be any element of $n\cup\{n\}$.

If $n=0$, then $x=n$ since $x\notin n$.

And $x=n\in\mathbb{N}$.

Suppose $n\neq 0$.

Let $x$ be any element of $n\cup\{n\}$.

If $x\in n$, then $x\in\mathbb{N}$ by induction hypothesis.

If $x=n$, then $x=n\in\mathbb{N}$.So, by induction, if $n\in\mathbb{N}$, then for any $x\in n$, $x\in\mathbb{N}$.

Convention 1 works perfectly anytime.

Why?