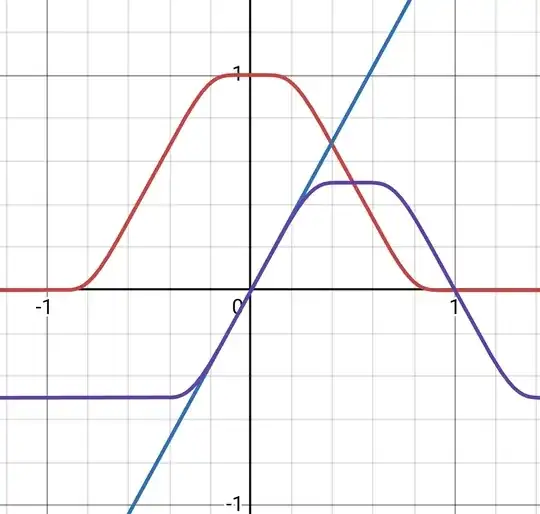

I would like to formulate a bump function (link) $f:\Bbb R \to\Bbb R$ with the following properties on the reals:

$$ f(x) = \begin{cases} 0, & \mbox{if } x \le -1 \\ 1, & \mbox{if } x = 0 \\ 0, & \mbox{if } x \ge 1 \end{cases} $$

In addition (because it's a bump function), it should be smooth and continuously differentiable, and the first-order derivative at $x = -1$ and $x = 1$ should be zero.

But one last stipulation defeats me. I would like it to be the case that

$$ \int_{-1}^1 f(x) dx = 1 $$

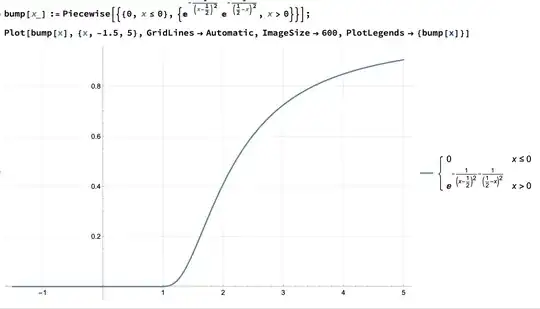

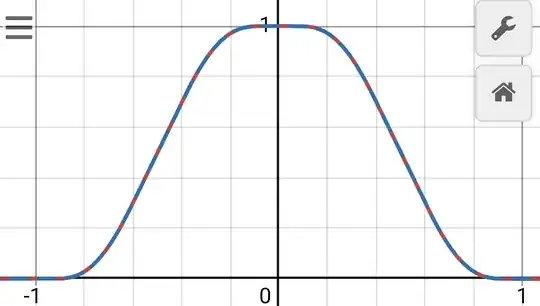

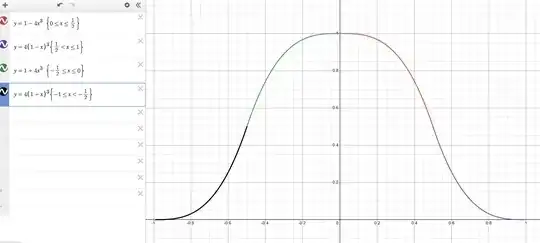

The example of a bump function offered in the Wikipedia article linked above comes close (I have added $1$ to the exponent to take it to a value of $1$ at $x = 0$):

$$ g(x) := \begin{cases} 0, & \mbox{if } x \le -1 \\ \exp^{1-\frac{1}{1-x^2}}, & \mbox{if } -1 < x < 1 \\ 0, & \mbox{if } x \ge 1 \end{cases} $$

The function $g$ answers all my requirements except $\int_{-1}^1 f(x) dx = 1$. And here I hit a wall. I assume that, in principle, one could multiply $x$ by some factor $a > 1$ to obtain the precise result required... But that would require having a formula for the antiderivative $\int \exp^{1-\frac{1}{1-ax^2}} dx$, and I have no idea whatsoever how to find it. The usual techniques don't seem to apply. Furthermore, Mathematica just shrugs - which suggests to me that I could spend a very long time trying and make no progress at all.

So:

- Is $g(x)$ in fact integrable (in the sense of producing a formula for the antiderivative)? If so, how?

- If not, then is there a completely different formula that would satisfy the conditions set out for $f$? I really don't know how to begin constructing such a thing since my math knowledge of the properties of various classes of functions simply isn't up the task.

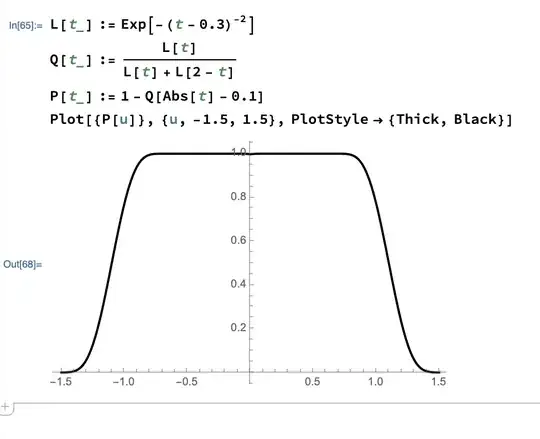

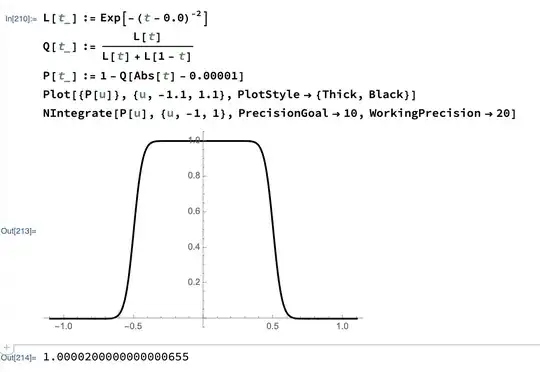

UPDATE AFTER SUGGESTION IN COMMENTS

I have looked at the answer here (many thanks @Lorago, I searched for "bump function" here but this didn't come up for me), but cannot make it work. Perhaps I am doing something wrong? As per the answer there, set

$$ f_0(x) := \begin{cases} 0, & \mbox{if } x \le 0 \\ e^{-\frac{1}{x^2}}, & \mbox{if } x > 0 \end{cases} $$

I can see that the function $f_1(x) := -e^{-\frac{1}{x^2}} + 1$ would produce a positive bump with $f_1(0) = 1$; though since $f_1(x) \rightarrow 0$ only as $x \rightarrow \pm \infty$, I am not sure of the utility of it. The choice of a piecewise cut-off at $x = 0$ for $f_1 (x)$ also seems odd.

However, let's go with it. The next step in the answer is to set

$$ g_0(x)=f\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)f\left(\frac{1}{2}-x\right) $$

So,

$$ g_0(x) := \begin{cases} 0, & \mbox{if } x \le 0 \\ e^{-\frac{1}{(x - \frac {1}{2})^2}} \cdot e^{-\frac{1}{(\frac {1}{2} - x)^2}}, & \mbox{if } x > 0 \end{cases} $$

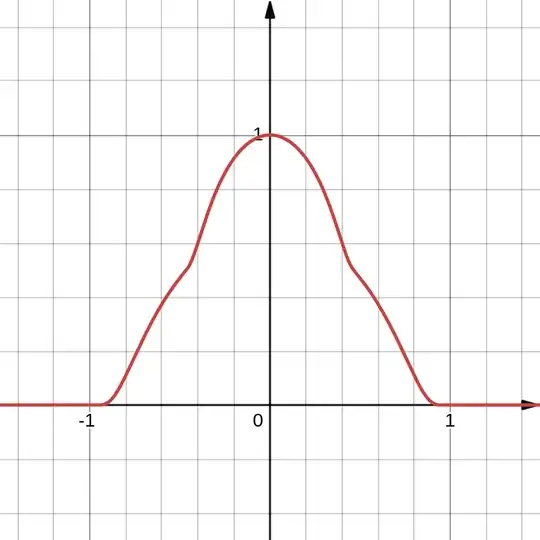

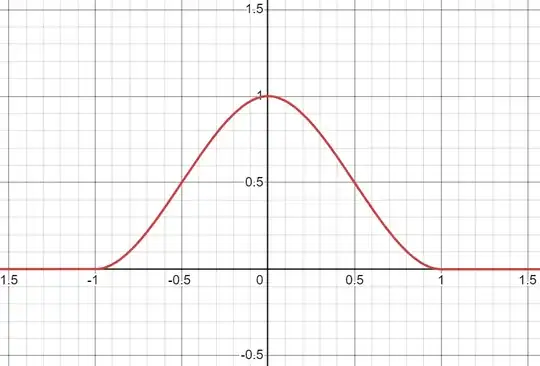

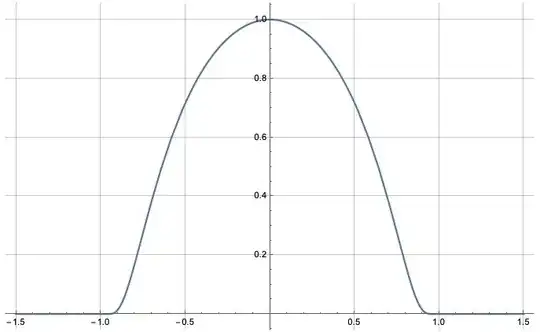

The linked answer states "This is a smooth bump function centred at the origin, but $g_0(0)\neq1$." But I beg to differ; here's a plot:

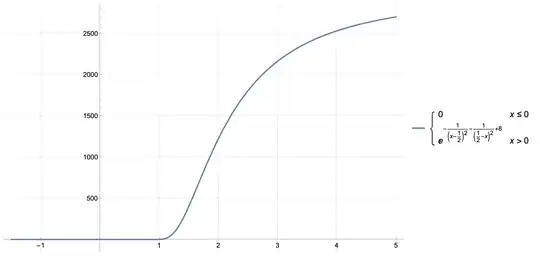

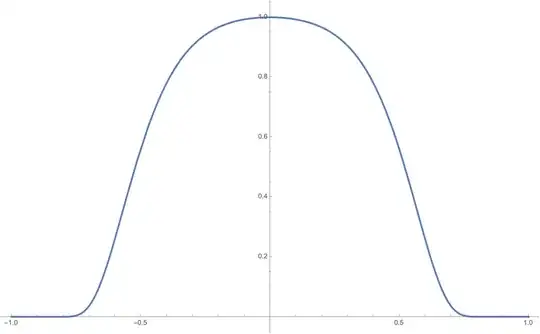

Clearly, I have deeply misunderstood what is being suggested. But for the sake of completeness, now set $g_1(x)=\frac{g_0(x)}{g_0(0)}$. Mathematica makes the following simplification:

$$ \frac {e^{-\frac{1}{(x - \frac {1}{2})^2}} \cdot e^{-\frac{1}{(\frac {1}{2} - x)^2}}}{e^{-\frac{1}{(- \frac {1}{2})^2}} \cdot e^{-\frac{1}{(\frac {1}{2})^2}}} = e^{-\frac{1}{\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2}-\frac{1}{\left(\frac{1}{2} - x\right)^2}+8} $$

So, we now have

$$ g_1(x) := \begin{cases} 0, & \mbox{if } x \le 0 \\ e^{-\frac{1}{\left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right)^2}-\frac{1}{\left(\frac{1}{2} - x\right)^2}+8}, & \mbox{if } x > 0 \end{cases} $$

This is proposed as the solution. But it looks like this...

Even allowing for the fact that one might have made adjustments to $f_0$ to produce something more like $f_1$ with appropriate piecewise cut-offs, it's easy to see that I am doing something deeply wrong.

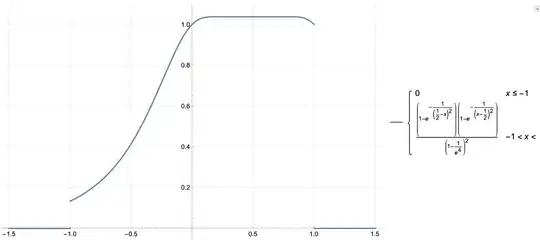

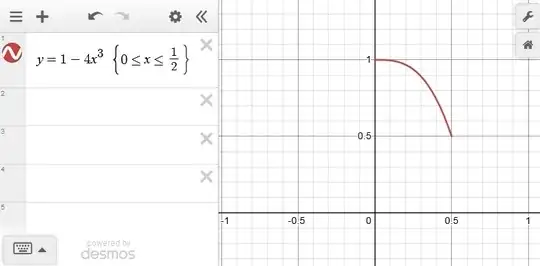

For completeness, here is a plot of the same process applied to $f_1$, with appropriate adjustments to the cut-off points for the piecewise specification. It's marginally closer but still does not address most of the requirements:

Sadly, despite the previous answer, I find myself still in need of assistance.