$\mathbf {dx}$ is a so called differential form, that is a locally linear function on local vectors $\mathbf v$ along curves of points $\mathbf P= \mathbf x = (x,y) \in \mathbb R ^2$, defined by

$$\mathbf{dx}\left (\ v_x(x,y)\ e_x(x,y) \ + \ v_y(x,y) \ e_y(x,y)\ \right) \ = \ v_x(x,y).$$

$\mathbf {dx},\mathbf {dy}$ may be defined by their action on the gradient field of a function

$$\mathbf dx((\partial_x f(x,y),\partial_y f(x,y))=\partial_x f(x,y)$$

especially on the linear coordinate function themselves

$$\mathbf {dx}(\partial_x x)=1, \mathbf {dx}(\partial_y x)=0 $$

and their inverses as integrals along curves

$$\int_{C= (a x +b,d y + e)} \mathbf {dx} = \int_{C= ( \xi +b,d y + e)} \frac{ \mathbf {d\xi}}{a}$$

A differential of first order is an equation between those linear functions

$$ \omega (\mathbf v (\mathbf x))= \sum_i a_i(\mathbf x )\ \mathbf {dx}_i(\mathbf v (\mathbf x)) = 0$$

Such an equation makes sense by the trivialities of linear algebra: the linear functions to the number field form a linear vector space, too, called the dual space. So the linear combinations of differential forms are a differential form. In other words, if points on parallel lines define vectors, families of parallel hyperplanes define the linear space of 1-forms.

The zero of such a differential form eavluated on vectors defines a vector field, that is a local field of directions in n-dimensional space.

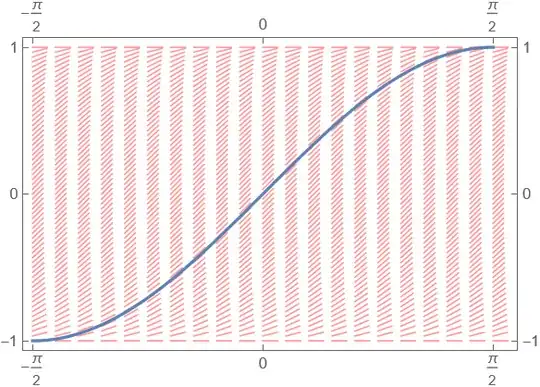

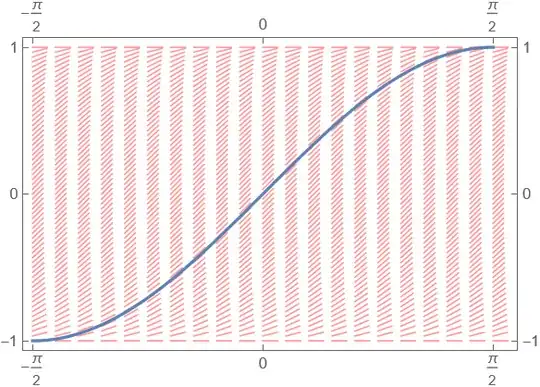

The differential equation for sine function

$$y'=\sqrt{1-y^2}, \quad \omega = \mathbf {dy} - \sqrt{1-y^2} \mathbf {dx} =0 $$

yields the following vector field

\[Omega][x_,y_]:= Line[{{x,y}, {x,y}+0.1 ( #/Norm[#]&)[{1,Sqrt[1-(y)^2]}]}]

Graphics[{{Opacity[0.4], Red,

Table[[Omega][x, y], {x, -[Pi]/2, [Pi]/2, [Pi]/20}, {y, -1, 1, 1/30}]},

{Plot[Sin[x], {x, -[Pi]/2, [Pi]/2}][[1]]}},

Frame -> True, FrameTicks -> {{-[Pi]/2, 0, [Pi]/2}, {-1, 0, 1}} ]

To solve a differential equation of first order means to find in a family of differentiable curves $\mathit C_{\mathbf x_0}$ fitting such a 2d vector fields and passing throug a given point $\mathbf x_0$

$$s\to \mathbf x\left( s, \ \mathbf x_0\right),$$

such that the action of the differential form onto its tangent at all points yields zero.

Only in two dimensions there is the simple identity

$$f\left(y',(x,y)\right) \ = \ 0 \ \leftrightarrow y' = f^{-1}(x,y) \leftrightarrow \mathbf{dy}= f^{-1}(x,y) \ \mathbf {dx}$$

As you see in the image, beware of points $(x,y=\pm 1$ where the inversion of the coefficient functions isn't working.

If $ f(y',(x,y)) =0 $ is linear in $y'$ one has a simple linear form. Only of the coeffients separate, the differential form is exact,

$$y'= f(y) g(x) \ \leftrightarrow \ \frac{dy}{f(y)} - dx \ g(x)=0$$

and their integrals can be done directly and differ by a constant.

In general, a differential form is not the differential of a function, but it's possible to find an integrating factor $\mu(xy)$, such that there exists a solution function $g$

$$\mathbf {dx} \ \partial_x g(x,y) + \mathbf {dy} \ \partial_y g(x,y) = \mu(x,y) \left(\mathbf {dx} \ - f(x,y) \mathbf {dx} \right) ==0$$

Its typical, that solutions of an ordinary differential equation are presented by the zero of a family of functions of several variables.

Often the inverses are defined as series of a 'special function' with the same name as the defining equation.

This scheme is universal for systems of explicit ODE's of any order: they can always be reduced to linear systems of first order by renaming all derivatives as independent variables, exceptfor the two highest derivatives in

$$y^{(n)}(x) = F\left(y^{(n-1)}(x),\dots y(x)\right)$$

$$y^{(n)}\to z_{n-1}'(x),\quad y^{(k)}(x)\to z_k(x) $$