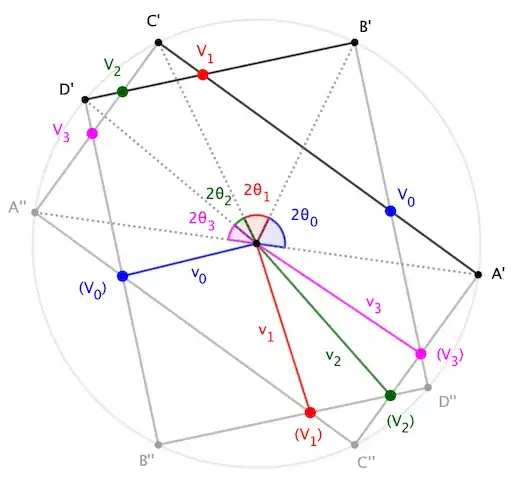

Inspired by Sangaku problems such as these, I created the following Sangaku problem.

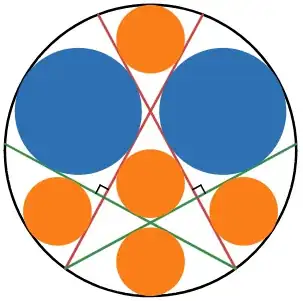

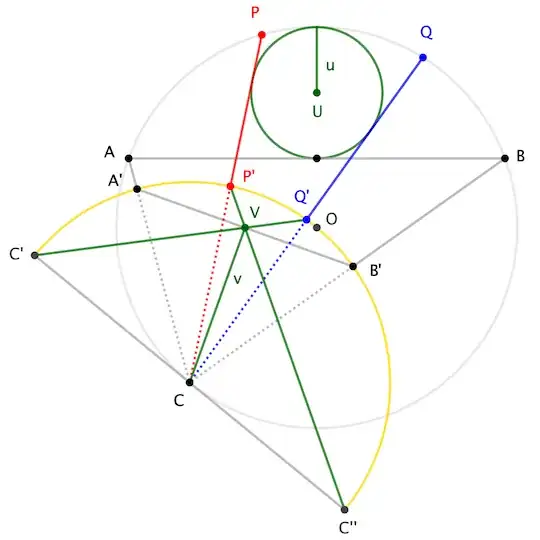

Consider the following diagram.

Description: The diagram shows the circle $x^2+y^2=1$, two red chords with equations $y=\pm mx+k$ where $m>1$ and $0<k<1$, and two green chords that each meet one of the red chords on the circle below $y=0$ and is perpendicular to the other red chord. The values $m$ and $k$ are chosen so that there exist two blue circles inside the unit circle that are reflections in the $y$-axis, the left of which is tangent to: the unit circle, the chord $y=mx+k$ at the midpoint of the chord $y=mx+k$, the chord $y=-mx+k$, and the chord perpendicular to $y=mx+k$.

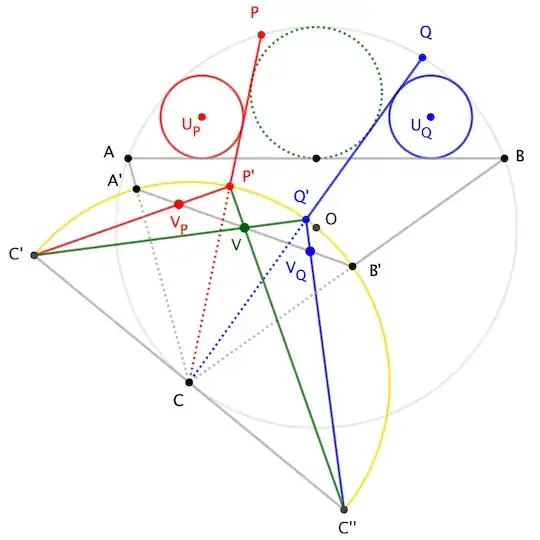

Inscribe five orange circles as shown below. (The orange circles are inscribed in every previously unoccupied region except the two triangles.)

Show that the five orange circles have equal radii.

I have a computer-assisted solution. I am looking for a computer-free solution.

My computer-assisted solution

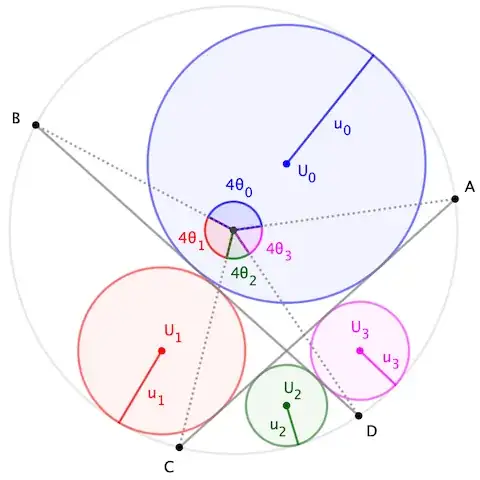

Define the following four points:

- $(x_1,y_1)$: Point where the right blue circle touches the chord $y=-mx+k$.

- $(x_2,y_2)$: Point where the right blue circle touches the unit circle

- $(x_3,y_3)$: Centre of the right blue circle

- $(x_4,y_4)$: Lower-left point where the chord $y=mx+k$ meets the unit circle

$x_1$ is the average of the sum of roots of $x^2+(-mx+k)^2=1$, so $x_1=\frac{mk}{1+m^2}$ and $y_1=\frac{-m^2k}{1+m^2}+k$.

$x_2$ is the larger root of $x^2+\left(\frac{x}{m}\right)^2=1$, so $x_2=\frac{m}{\sqrt{1+m^2}}$ and $y_2=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+m^2}}$.

$x_3=\frac12(x_1+x_2)=\frac12\left(\frac{mk+m\sqrt{1+m^2}}{1+m^2}\right)$ and $y_3=\frac12\left(\frac{k+\sqrt{1+m^2}}{1+m^2}\right)$.

The distance from $(x_3,y_3)$ to the chord $y=mx+k$ equals the radius of the right blue circle, which is $R=\frac12\sqrt{(x_1-x_2)^2+(y_1-y_2)^2}$. This gives one equation with $m$ and $k$.

$x_4$ is the smaller root of $x^2+(mx+k)^2=1$, so $x_4=\frac{-mk-\sqrt{1+m^2-k^2}}{1+m^2}$ and $y_4=\frac{-m^2k-m\sqrt{1+m^2-k^2}}{1+m^2}+k$. The centre of the right blue circle, $(x_3,y_3)$, lies on the line that passes through $(x_4,y_4)$ with gradient $1$. This gives another equation with $m$ and $k$.

With help from Wolfram, I solved these two equations to get an approximation of $m$, then put this approximation back into Wolfram, which suggested it is the real root of a certain cubic polynomial. Using this method, I got:

- $3m^3-6m^2+3m-4=0\implies m\approx1.8491482$

- $17k^3-33k^2+30k-6=0\implies k\approx0.2681854$

- $17R^3-54R^2+57R-16=0\implies R\approx0.4362138$ ($R=$ radius of blue circles)

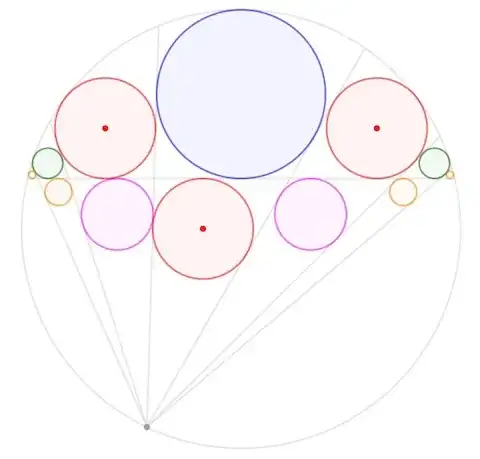

Let $S$ be the radius of the orange circle nearest the centre of the unit circle. It is easy to show that $\frac{R}{S}=m$ (note that the obtuse angle between the green chords equals the obtuse angle between the red chords, then compare the central orange circle and a blue circle). Again with the help of Wolfram, this gives:

- $17S^3-30S^2+57S-12=0\implies S\approx 0.2358999$

Assuming that the five orange circles have equal radii, I used the closed forms for $m,k,R,S$ to make a desmos graph of the diagram, and all the circles and chords fit together perfectly.

Fun fact: The centres of the top four circles are the vertices of a square.

This comes from the fact that the distance from the centre of the top orange circle to the intersection of the red chords, which is $1-S-k$, equals $x_3$.