Question:

For $n \in \mathbb{Z}^+$, define $Z(n)$ to be the number of ones in the binary expression of $n$. For fixed positive integer $a$, how does one describe the set of $b$ such that $Z(ab) = Z(a)Z(b)$?

Bounty Added (Jun 6, 2024):

So far there is one answer provided, and I received a similar answer by email that I paste below; additional ideas and reference pointers are most welcome!

Edit (Jun 4, 2024): In response to two different comments: Corrected an image and introducing Hamming weight, which (in the case of binary strings) refers to the total number of ones in a string. With this additional vocabulary item, the main question can be rephrased as asking when the Hamming weight is multiplicative.

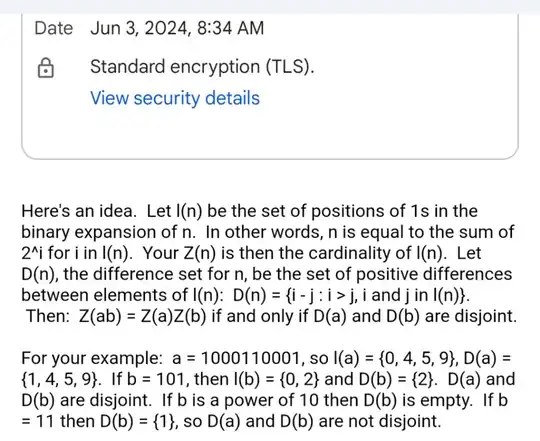

Edit (Jun 3, 2024): I used GPT-4 (link) to create graphs with the following query:

consider a positive integer n. define Z(n) to be the number of ones in the binary representation of n. create a 100 by 100 graph where (a,b) is colored black if Z(ab)=Z(a)*Z(b), and colored white otherwise.

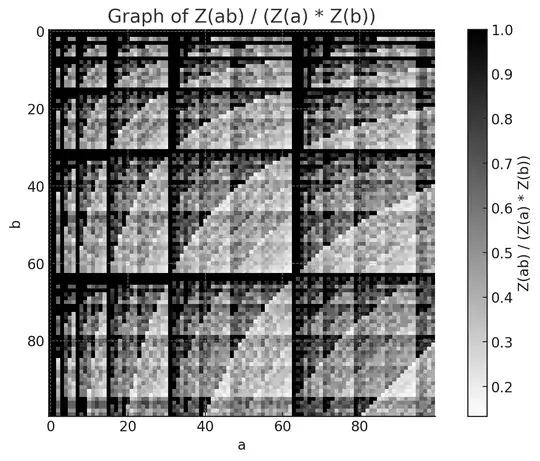

Here is an image of the graph that was produced:

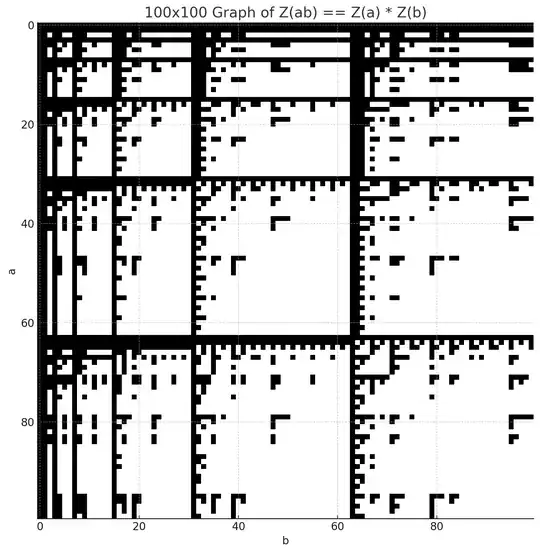

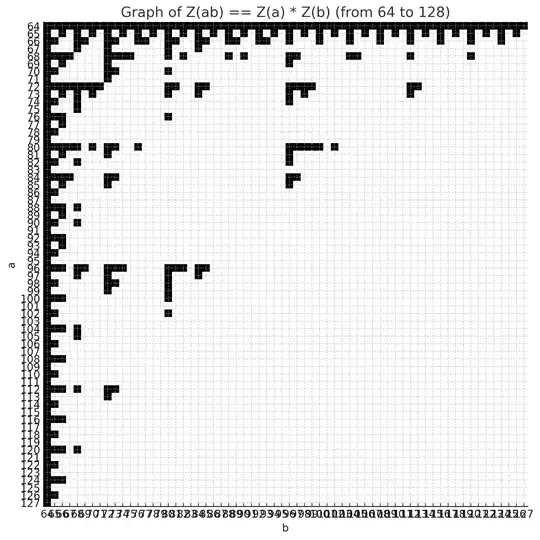

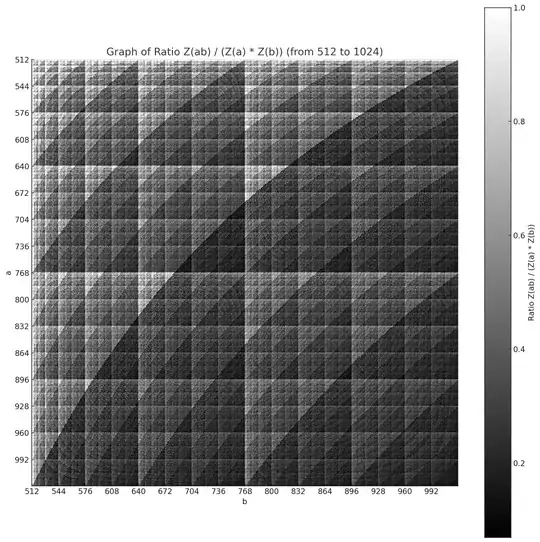

Because of a pattern that looks like the Sierpinski Triangle in the bottom right hand corner of this graph, I followed up by specifically printing graphs where both $a,b$ are in the range $[64, 128]$ and then $[128,256]$. Those images are pasted below:

I suspect this Sierpinski pattern holds for $a,b$ in $[2^k, 2^{k+1}]$ for large $k$, but am not sure how to prove it. Ideas in this direction are welcome, although the intention of this initial question is the bolded question of the top.

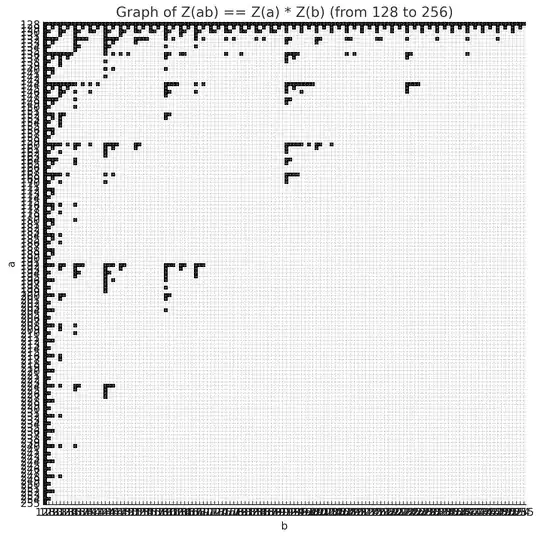

Edit asked by author (Jun 8, 2024):

Beautiful $100\times100$ plot (generated by GPT-4o) of the ratio $Z(ab)/(Z(a)Z(b))$ as shades of gray, as dvitek proved that this ratio was in $[0, 1]$.